A Chicago professor's obsession with a single strand of hair leads her to create face sculptures of random strangers—from DNA extracted from bits of trash they leave behind. These creepy creations pose big questions when it comes to privacy and state surveillance.

Think of the dread you’d feel if you lost your wallet on a busy street. Or the sinking feeling in your gut if you forgot your phone in a crowded restaurant.

But you probably wouldn’t think twice about brushing aside a strand of your hair in a public bathroom, or tossing away a plastic coffee cup, a piece of chewed-up gum, or a cigarette butt.

Maybe it’s time to think again.

What you discard most likely contains your DNA, that is, your entire genetic material, something scientists can use to determine everything you were born with—your race, bone structure, complexion, eye color, the shape of your face, and so on.

But, unless you’ve committed an interesting crime, no one is likely to pick up and study the debris you leave in your wake. No one, that is, except Heather Dewey-Hagborg, a “bio-artist” who constructs 3D portraits of people from the DNA she extracts from such leavings.

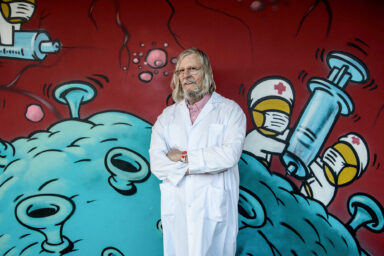

Photo courtesy of Heather Dewey-Hagborg.

A Single Strand of Hair

It all started in 2012 when Dewey-Hagborg noticed a single strand of hair stuck in the frame of a picture hanging in a therapist’s office.

“I just sat there and stared at it,” she recalled in an interview with WhoWhatWhy, “and I couldn’t stop thinking about whose hair it might be. It struck me that we were leaving DNA all over the place, all the time, and not giving it a second thought.”

It’s understandable why this would be so interesting to Dewey-Hagborg, when one considers her background. Among other things, she has studied art, computer science, machine learning, artificial intelligence, two-dimensional facial recognition and face-generating algorithms, molecular biology, DNA extraction, and DNA amplification by a technique known as polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Her obsession with that single strand of hair led her to New York’s Genspace, a community bio-tech lab. She made it her goal to find other such human material and, using the DNA left in it, to create a “face sculpture” of the stranger who left it behind.

From Trash to Art—and Identity

From Trash to Art—and Identity

Scouring the streets of New York for trash was the easy part. Getting usable DNA from the trash was the real challenge. “I spent six months in the lab and every experiment I tried, I failed,” she said. “But I kept going and going and going.”

When Dewey-Hagborg finally managed to isolate a piece of DNA code that she could use—a SNP, or single nucleotide polymorphism—she remembers thinking: “This can actually happen. I can make this work.” And, with the help of an outside lab that did the genome sequencing, she did make it happen. (Click here for more information about genome such sequencing.)

Combining the skills she had mastered in facial-recognition software with the services of an adapted 3D printer, she made the leap from facial “recognition” to “re-creation.” Her first subject was herself.

Using nothing but DNA from a strand of her own hair, she created a sculpture that closely resembled her own face. Like most artists in history, she notes with a laugh, her first work was a self-portrait.

Early this year, just as Dewey-Hagborg was moving to Chicago to take up a teaching job at the School of the Art Institute, her creations caught the eye of a Chicago gallery director.

“(We) were fascinated instantly by these 3D prints and how they came to be,” Juli Lowe, of the Catherine Edelman Gallery, told WhoWhatWhy. “From an art standpoint… I think what she is raising are very important questions.”

And now on display at that gallery, is a whole series of faces created from DNA by Dewey-Hagborg, called “Stranger Visions.” Each sculpture is paired with the discarded object that “birthed” the face, along with a description and photo of where the object was found.

So far, none of the “models” have come forward to claim their faces. So how does Dewey-Hagborg know she’s gotten a face right?

She readily admits that “it’s entirely possible that I could make a portrait of someone from their DNA, and they could look significantly different than that.”

Whatever the DNA may say, an individual’s life history and habits may alter the “phenotypic” expression of the genes—as in the case of a seriously obese person.

In fact, Dewey-Hagborg says, the true motivation for “Stranger Visions” isn’t art, or trying to get the face exactly right; it’s to get people thinking about the privacy issues raised by what she calls “genetic surveillance.”

“I could have taken that same DNA sample and created a much more comprehensive portrait that I think is a much stronger invasion of privacy.”

“For me, this project was about answering a question, which was, ‘How much can I learn about a person from some little bit of themselves they left behind?’ I do feel that I have answered that question and the answer is a whole lot,” Dewey-Hagborg says. “It’s an enormous privacy problem that we have to be talking about.”

For Good or Ill

Law enforcement agencies around the world are exploring the use of forensic DNA “phenotyping,” as it’s called. The US Justice Department is giving a $1.1 million dollar grant to Indiana University to further develop the science. Someday it may be possible to reconstruct entire genetic profiles this way.

With law enforcement pushing hard to develop phenotyping technology, Dewey-Hagborg asks: ”What do we think of that? With everything in science, there’s potential and there’s risk.”

For example, phenotyping could be used to identify a crime victim from the remains of a body. But using it to racially profile a crime suspect would be “problematic,” she says.

Dewey-Hagborg’s next project is teaching a course on harnessing such new technologies for socially constructive purposes. “We need,” she says, “to decide how this will be used in our society.”