Satire failed us during the rise of Trump, but maybe that’s because we were using it wrong.

|

Listen To This Story

|

It is beginning to feel like the years of the Biden presidency have been one long commercial break. From 2021 on, the advertisements have tried to sell us on such things as “a return to normalcy” and an “Inflation Reduction Act.” Those who still have cable are perpetually being sold 24-hour news about normal wars in the usual places and weight-loss drugs sold with a wink as diabetes medicine.

What we thought was a restoration of the old order may just be an interregnum.

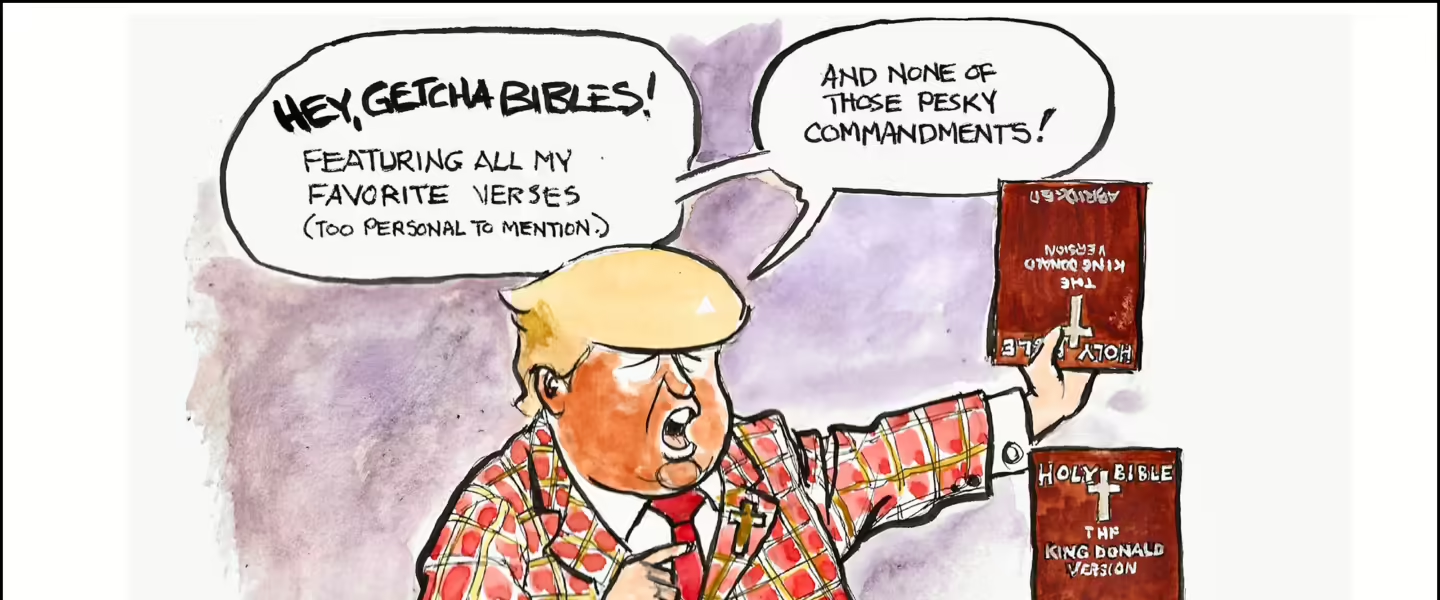

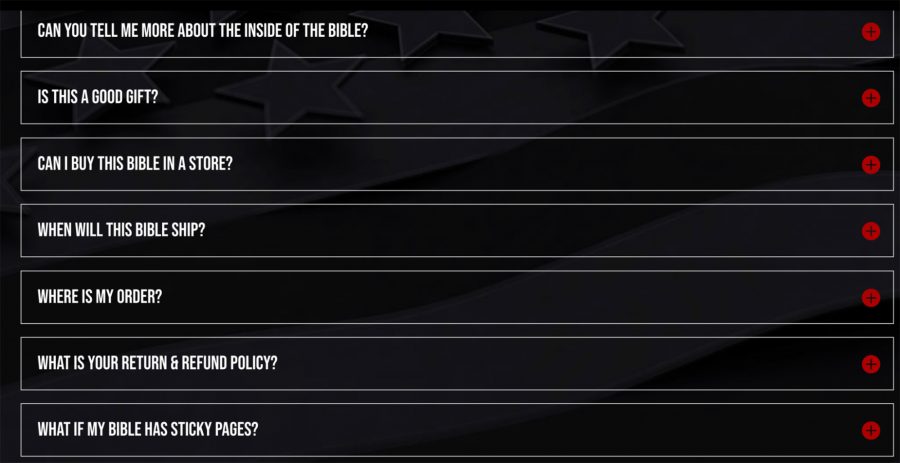

Because the Commercial Break of America is drawing to a close. We are about to return to the show. I thought this after my friend Kevin texted me an image from the FAQ page for the “God Bless the USA Bible,” which is “the only Bible endorsed by President Trump!” and additionally, “the only Bible endorsed by Lee Greenwood!” The noteworthy bit is a little farther down the page:

Sticky pages? Sticky pages? Nevermind that the explanation is a redundant “gold gilding” and that the solution is a helpful YouTube video “explaining how to break your new Bible in.” I laughed at it, but then caught myself. Am I laughing at the idiocy of sticky Bible pages or is someone somewhere laughing at me for thinking that any of it is intended to be earnest?

The God Bless the USA Bible sells for $59.99, the profits from which will accrue to Donald Trump. What makes this Bible innovative is what it adds to the standard-issue King James translation, per the website:

This Bible also features a copy of:

-

-

- Handwritten chorus to “God Bless the USA” by Lee Greenwood

- The US Constitution

- The Bill of Rights

- The Declaration of Independence

- The Pledge of Allegiance

-

“All Americans need a Bible in their home and I have many,” Trump said in the promotional video for the Bible. “It’s my favorite book. It’s a lot of people’s favorite book.”

This is all very funny. It’s the old Trump schtick, but it still lands: The Bible is Trump’s favorite book, and he has many of them. The pages may be sticky. This Bible improves on the classic Bible by making it an American Bible, complete with America’s founding documents and lyrics to a song that links the God of the Bible with the America of the Constitution. It’s funny, but it’s also… familiar. Deeply familiar. We know this bit. The Inflation Reduction Act may not have been inevitable, but the God Bless the USA Bible certainly is.

The takeaway for me is that this is a sign that we’ve left the predictable normalcy of a commercial break and returned to the show we’ve been in since around 2015. It’s a show that is a satire that devours satire. It is a show that stars Donald Trump but that is really about all of us reacting to Donald Trump. The tagline for the show should not be the most popular slogan of the modern era — Make America Great Again. It should be Of Course.

And as you may remember, back before the Commercial Break, we in the news media collectively did a pretty bad job of interpreting the meaning of Trump; what the show was about, who it was for. There are a lot of reasons for that, but a couple are relevant here: The news media in general has no sense of humor, and the entertainment media thought it entirely controlled and determined what was funny. But now here we are, with a second chance to figure this show out.

Then as now, what seems most important to me is that the rise of Trump was both absurd and inevitable, and, then as now, the best way to understand it is through the language of myth.

A recurring theme for commentators of Trump’s first campaign and presidency was a riff on whether he was some sort of Trickster. Here’s Carol S. Pearson, writing in June 2016:

All the attention on [Trump] suggests to me that the Trickster archetype is reemerging in our time, forcing us to make this archetype conscious so that we can gain its gifts and avoid its downsides. Besides its political manifestation, the Trickster in each of us also can be an agent for good or result in a whole lot of trouble for everyone concerned.

Tricksters abound in all cultures. Generally, they achieve their goals through trickery, and in the process undermine traditional rules about how things are done. Often, but not always, they truly enjoy the process.

And here’s Randy Fertel, writing for Washington Monthly in December 2017:

The archetype that Trump is unconsciously channeling is not Hero, but Trickster. … Trump’s Trickster identification seems to swing between Hermes, culture-bearer, and Dionysus, whose appetites are of the chaos-generating sort. What Trickster and Trump share is a commitment to spontaneity and improvisation that makes do with available materials and always pushes the envelope.

All this Jungian woo-woo appeals to me. A cycle ends, a cycle begins. The thing called “Trump” was bound to happen. If you’re not a fan, he is the boil pushed out by the sickness in American culture. Or if you’re pro-Trump and enjoy the Dune movies, perhaps you see him as America’s Paul Atreides, the result of a multigenerational breeding program here to lead a holy war that will unite the galaxy. Possibly he’s brandishing the God Bless the USA Bible in his march across the stars.

I’m a fan of that reading. It’s reassuring to me, this idea that we’re living inside a narrative. Themes can be discerned, hackneyed tropes can be trotted out again. Even at the level of history — especially there — it’s all a story. I mean, I’m a storyteller, so of course this appeals.

But the mainstream wasn’t having it. Archetypes be damned! The overwhelming sense from the news, late-show hosts, and political comedians during Trump’s first run and first reign was that we were about to tuck into some serious entertainment: Let’s watch the strutting, gold-gilded ass finally collapse under the weight of his hubris.

You saw it everywhere. In August 2015, Vanity Fair ran a retrospective on Spy Magazine, a satirical publication started by Kurt Andersen and VF’s own Graydon Carter. Spy was very late-20th-century New York; early on, it identified the absurdities of Donald Trump, famously dubbing him a “short-fingered vulgarian” and tongue-in-cheekingly promoting him as a presidential candidate way back in 1988. The Vanity Fair article came out soon after Trump announced his actual presidential run, and it brims with the confidence that this would be the greatest of Trump’s failures and an ultimate justification for Spy’s long-running bit on his deluded ambitions:

In the end, I have faith that just as Americans ultimately decided that Sarah Palin wasn’t qualified to be a heartbeat away from the presidency, they’re not about to let The Donald get even closer.

Short-fingered or not, on so many, many levels, the presidency is beyond his grasp.

That article didn’t see what was coming because it was a product of the old order, and Trump’s project was to upend the old order. He became the Court Fool whose singular position as outsider empowered him to make fun of the King as a kind of social pressure-release valve. Even this got screwed up. The Fool became King while still, somehow, retaining the power of the Fool. The one responsible for maintaining order was the same one who was also undercutting it. A good joke. The best joke! A lot of people are saying this.

This led to a metaphysical problem for the appointed court jesters — comedians who could not keep up with the pace of this new reality. No stand-up or writers’ room could generate a joke that wasn’t soon matched by the absurd actions of the administration. As a New York Times story put it in October 2020:

In theory, Trump should be the best thing that ever happened to liberal comedy. Five years ago, when he announced his candidacy after descending an escalator in a mall/apartment complex bearing his name, it briefly appeared as if he might be. Like so many others, this hope has not panned out. Maybe it’s the glut; in any form of humor, from sitcoms to barroom remarks, overproduction causes trouble. But there is also a sense, as the president talks openly about defying the results of the election, that satire has not accomplished what its champions believed it could.

And now, here we are again, coming out of a commercial break into who knows what this next act is. Certainly, if you read the gospel of the Sticky Pages Bible, you’ll know that the Trickster is still afoot. Some of the same old tricks, though, so what did we learn from last time around?

For one thing, we know that everyone was wrong about what satire was good for. Look at Spy Magazine. It didn’t keep Trump in his place. It did something weirder. Its satire predicted the absurdity of what was coming. The news was wrong about the future, but the fiction was right.

Way back in April 2021, with January 6 still fresh in mind, I had a conversation with Andersen about what satire was even supposed to do anymore. I asked him about being a Trump seer and, true to form, his answers still resonate three years later:

If you’re doing your job, you’re bound to just sometimes have reality catch up with you. And with this character — who back 35 years ago when we started doing Spy was like a fictional character — it makes sense that he catches up with the satirical fiction, and overlaps with it.

I have nothing magical or prophetic or anything else but the ability to kind of get it right sometimes just by combining close observation of the real world with what fiction lets you do — which is, you know, not stick to the facts.

Andersen’s writing — as journalist and novelist — has often come back to this idea: As entertainment and politics have merged, fiction becomes a useful way to predict outcomes, because everybody’s following some script or other.

This is, to me, both inspiring and depressing. Inspiring that a smart use of journalism’s skill-set run through the subterranean neon river of the imagination can create a vision of how things might turn out. Accurately modeling the future is great — religions have been started with less.

But that’s where it gets depressing. Because (and I only have access to this one universe, so bear that in mind), it doesn’t seem like it changes anything.

Andersen’s thought on that:

If you really want to change the world, you should be in a different line of work. However, I think preaching to the choir, if you do it beautifully and well, is an underrated thing. I think the choir needs preaching to in this comedic way. Maybe instead of being the people who make bandages for those wounded in fights, or soup for the soldiers, you’re making everybody have some pleasure and a deeper, sharper understanding of the issues than they would have otherwise.

Here’s a guy who wrote some of the most interesting and astute stuff on Trump over the years, and so I was surprised when I asked him what he thought about how to talk about Trump moving forward:

I haven’t been of a mind that, oh, Trump has ruined satire and comedy as much as many people. However, get him out of the picture and you can focus on complicated ideas where it’s not just him and his horror show — where it can be subtler and more interesting. Taking him out of the equation, but leaving all that he exploited and embodied and everything else here — which, it’s not going away — actually does set up an opportunity to interrogate and problematize our culture and our society.

The Trickster’s whole deal is that he comes in and upsets the established, ossified order so that society can build something better out of the mess. If Trump was the main character before the commercial break, maybe as we return to our show we don’t focus on him at all, but on solutions to the mess we allowed him — we created him — to make. What a twist.