Events on other continents created pressures leading to Kennedy’s death.

|

Listen To This Story

|

The JFK assassination cannot be properly understood without taking into account the environment in which it occurred.

At the time, America and the world were roiled by explosive events and controversies, perhaps even beyond the often-terrifying norm. As a dynamic, active leader of the most powerful country, Kennedy responded to these crises and opportunities, but not everyone liked his mindset and actions.

As I have found while working on a decade-plus book on the Kennedy assassination, the signs were everywhere that special interests were aggrieved by Kennedy.

Our media and history books have been derelict in bringing to public attention the mortal combat in which large American companies were locked with Kennedy.

In this installment of a series, I’ve chosen to highlight a single topic that has received inadequate public scrutiny — Western interests operating in poor, underdeveloped countries, and corollaries in US domestic affairs — as examples of the foreboding climate that preceded Kennedy’s fateful visit to Dallas on November 22, 1963.

Eisenhower Warned Us

In his January 1961 farewell address, President Dwight Eisenhower startled the country with a totally unexpected warning about a “Military-Industrial Complex.” The former general and World War II hero said,

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence … by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

An example of the troubling alliance between private companies and the US government happened just three days before JFK’s inauguration.

Large mining companies — some US-based and owned by politically influential titans — were alarmed by threats to their lucrative properties in central Africa and a breakaway region sponsored by the mining interests. The democratically elected Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba was murdered in captivity by separatist rebels. CIA-connected figures were later implicated. (News of his death before a firing squad would not reach the White House until much later; Kennedy was visibly distressed with the news.)

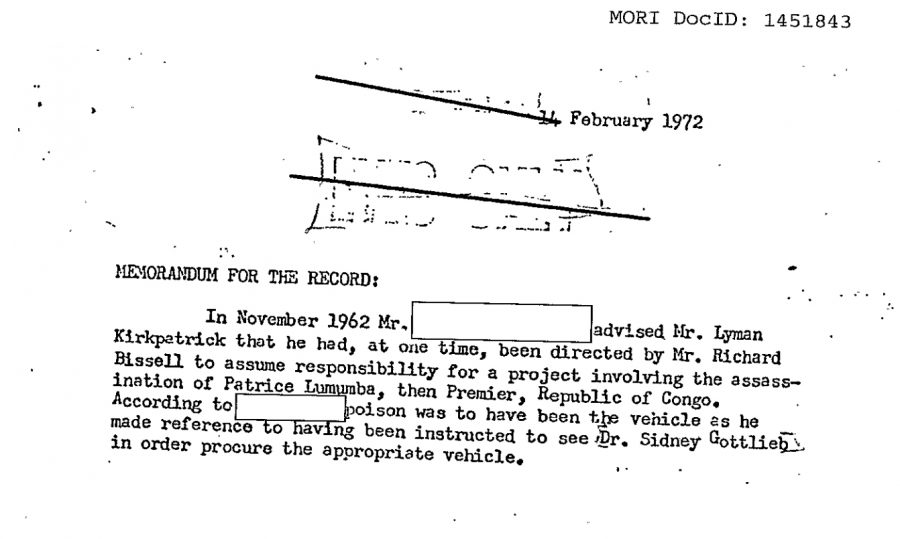

Had he not died before a firing squad, he would surely have been murdered by other means. Here, written in bloodless corporate language, is a bone-chilling message about a “project” involving the assassination of Lumumba, and “poison was to have been the vehicle.” Another version of this document can be found at the CIA Reading Room.

Eight months later, while personally overseeing UN peacekeeping activities in the Congo and trying to broker a ceasefire between armed separatists and the central government, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold died when his plane crashed just over the Congo border in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). Half a century later, evidence would suggest the plane was shot down by elements associated with US intelligence and mining interests.

The strategic and economic importance of these resources — and the incredibly high stakes involved — cannot be overstated, and there is a long history: Robert Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project to build atomic weapons as a means of defeating Japan in World War II relied extensively on uranium mined from the Belgian Congo.

One mining company with long-held, extensive interests in the area as of Kennedy’s election, AMAX, was controlled by powerful interests including the Rockefellers. A close ally was Kennedy’s only Republican Cabinet member and Eisenhower holdout Treasury Secretary Douglas Dillon. The family investment banking firm that Dillon had previously headed was deeply involved with Congo investments; he sat in on Cabinet meetings regarding the US response to the Congo crisis, which would have a direct effect on his family fortune.

Dillon was an extremely close friend of Eisenhower Secretary of State John Foster Dulles — and of Allen Dulles, the CIA director whom Kennedy fired around the time all this was going on. As treasury secretary, Dillon oversaw the Secret Service, which failed so stunningly on November 22, 1963.

In testimony in the 1970s, Dillon admitted that he was highly critical of Lumumba prior to the point where Lumumba was assassinated.

To this day, the Congo’s mineral wealth (copper, cobalt, gold, diamonds, uranium, tantalum) remains a source of civil conflict and international intrigue. And, emblematic of its paramount interest to the economy of the northern hemisphere, companies like AMAX (since absorbed by Freeport-McMoRan) are still there.

That dominance was challenged in many ways, often little-known, by foreign leaders, and Kennedy at times seemed sympathetic to the anti-corporate backlash.

In Cuba, the still fairly new leader Fidel Castro tangled with a host of American companies and interests, from sugar plantation owners to the wealthy mob bosses who had controlled the casinos in pre-Castro Cuba. With some corporate interests, Castro seemed able to get the better of them by turning their own duplicitous accounting practices against them.

Large foreign, mostly American, companies had extensive tracts of land lying fallow and unused, and Castro wanted to distribute them to peasants. The companies held out for large sums, but Castro offered to pay them the stated valuation, which the firms — in an echo of Donald Trump’s more modern selective inflation and deflation of assets — had deliberately understated for purposes of minimizing property taxes. Castro’s clever move enraged these foreign interests.

Meanwhile, Kennedy saw that some of what Castro was doing made sense as part of rectifying abuses from the long-lived plundering of the island nation — and though, as president, Kennedy was compelled to act on behalf of “US interests,” it was often with real doubts and, in the more extreme cases, outright resistance.

These matters have received much less attention than Kennedy’s reluctant assent to going forward with the Eisenhower administration’s plans for the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion (and his refusal to bring US troops into the picture), and his firmness in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Some who controlled major media empires were closely entwined with corporate interests benefiting from the Cold War and American military and intelligence dominance. Those same media empires later shaped the narrative of Kennedy’s assassination — and promoted the idea that Lee Oswald was a maladjusted young leftist who acted alone, not a “patsy” as he himself claimed after his arrest.

One example was Jock Whitney, from one of America’s wealthiest families, who, while he was Eisenhower’s ambassador to Britain, acquired the New York Herald Tribune, an influential Republican newspaper. Whitney was not happy that the editors of his paper responded with seeming enthusiasm to Kennedy’s victory in 1960.

When Kennedy took office, he quickly let Whitney know he would not be returning to London. (One US admiral claimed at the time that Kennedy had done so with a witty and ruthlessly brief telegram: “JOCK…PACK…JACK.”)

This of course pitted one son of wealth against another.

Whitney, along with members of other leading families, such as the Rockefellers, was a major player — actually had been the chairman and biggest shareholder — in the globe-girdling New Orleans-based mining company Freeport Sulphur (later Freeport-McMoRan).

Freeport had mining operations everywhere, including not just sulfur but uranium and nickel — the latter important in the steel and auto industries. It is also amazingly able to handle hot temperatures, making it indispensable to the nuclear industry, and of incalculable significance to military prowess — considered the “only true war metal.” It also played a unique and prized role in the oil-drilling business.

Freeport created the kind of business and social cohesion from which could come consensus on all manner of things. It was also expert in getting others — from governments to its customers — to directly fund much of its operations.

One source of contention concerned how aggressive to be with Castro. A battle by some of America’s richest people with the Castro regime over mining of the essential war mineral nickel generated a substantial CIA program. This included creating a front company in Canada so Cuban supplies still flowed, and engineering efforts to discredit Castro.

Freeport had built a huge nickel-processing plant outside its home base of New Orleans, but the raw materials came from nearby Cuba.

Castro wanted to end an overly generous tax exemption former Cuban President Fulgencio Batista had granted to Freeport for its huge Moa Bay nickel mine — but keeping the plant operating. As with many other companies, this ended unhappily. During a stalemate, the Cuban government took temporary control. This, coming just as Freeport began shipping nickel orders, was throwing down the gauntlet.

Kennedy shared Castro’s pique with the company. A December 18, 1962, New York Times article quoted officials on how they had been pressured to approve a 1957 nickel purchase for the government’s war-emergency stockpiling program, despite there being no nickel shortage — and the head of the office pressing for it was a friend of Nelson Rockefeller’s. Big names like Freeport’s titan Jock Whitney were being bandied about. At Kennedy’s request, the Senate began an inquiry. Importantly, the Rockefeller family had major holdings in three companies at the heart of the investigation, one of which was Freeport.

In early 1963, Kennedy press secretary Pierre Salinger declared that the stockpiling would be an issue in the 1964 campaign. So another big company had Kennedy in its cross-hairs. And aggrieved members of the establishment had one more reason to view Kennedy with alarm, as a threat to their interests and, perhaps, because of his stature and legal authority, to their reputations and more. (Adm. Arleigh Burke, chief of naval operations for the United States, who was instrumental in planning the Bay of Pigs invasion and supported killing Castro, later became a Freeport director.)

It’s well worth noting that strategic metals undergirded the ability of the US military to maintain dominance worldwide for American companies. Hence, it was of paramount importance to secure a continuing supply.

The representatives of corporate America in the Kennedy administration always had this uppermost in their minds. Castro’s nickel action alone was enough to obsess the American elite with taking him down. Allen Dulles, both as a Wall Street lawyer and as head of the CIA, had a continuous mission to secure these supplies. Of course, he and his allies had many grievances against Kennedy, and none of what I describe here is intended as the ne plus ultra of the laundry list. Still, these matters, among others, weighed heavily.

****

Kennedy, known from his early days in Congress as an enthusiast of allowing developing countries to carve their own unique destinies, advocated wherever he could for changes in how the US interacted with governments of newly independent or decolonized countries. He shifted US policy, again and again, in places like Laos and Vietnam and Indonesia, often subtly, away from the most oppressive and right-wing regimes to those taking a more neutral approach.

Especially in Africa — the hotspot of decolonization in the early 1960s — Kennedy espoused “Third Way” thinking, encouraging newly-independent governments to pursue democratic capitalism instead of communism or neo-colonial authoritarianism.

To this end he persuaded Congress to create the US Agency for International Development plus the Peace Corps, and to allocate economic development funds for countries such as Guinea, Ghana and the Congo. Kennedy chose ambassadors to such countries who knew how to navigate the twin pressures of neocolonialism and communism: For example, he made Edmund Gullion, a career diplomat who had shown Kennedy around French-ruled Vietnam in 1951, the US ambassador to the Congo.

The Kennedy administration also responded to strong pressure from African nations to stop supporting apartheid in South Africa: It announced in August 1963 a total arms embargo against the apartheid regime. All of this was a renunciation of Eisenhower administration policies, and Kennedy’s were initiatives widely opposed by much of the Washington establishment.

In the Middle East, Kennedy recognized the attraction of populist or nationalist figures like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, and he was determined not to allow the region to turn into another atomic tinderbox, resisting Israel’s efforts to develop nuclear weapons.

He spoke and acted in support of national liberation movements, even to the point of clashing with NATO allies Belgium and Portugal. And he was notably cautious about military solutions to post-colonial civil strife — brokering a peace deal among warring factions in Laos instead of intervening militarily, and balking at pressure from many sides to commit a heavy US troop presence to the defense of South Vietnam (“In the final analysis, it is their war. They are the ones who have to win it or lose it”).

Domestically, Kennedy took a hard line against corporate abuses in ways that shocked and angered the companies, whether pursuing antitrust action against the plastics and chemical giant DuPont or coming down hard on the steel industry after it betrayed his efforts to secure labor peace. (Today, Biden administration entanglements with fossil fuel extractors, big pharma, and other industries echo Kennedy’s clashes.)

Kennedy was equally tough on organized crime, which his holdover FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, claimed did not exist. His brother Robert, serving as attorney general, prosecuted leading figures including the mob bosses Carlos Marcello of New Orleans and Sam Giancana of Chicago, and the mob-allied Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa.

The president was locked in a kind of mortal combat with so many institutions, but perhaps the most important was the CIA — an organization that has since been implicated in numerous assassinations throughout the world. Kennedy was said to have declared to aides that he would “splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it into the winds.”

After Kennedy was murdered, a great deal changed; some of the progress Kennedy initiated was carried forth, but his efforts to rein in the most powerful halted abruptly. However, people didn’t realize that — in part because of a determined effort to shape public perceptions and hide the truth that has continued for decades, and, to some extent, to the present day.

That staunch resistance to leveling with the public was well described by G. Robert Blakey, the nation’s foremost authority on the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO), who had been chief counsel and staff director to the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA). In 2013, the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s death, Blakey told the Las Vegas Sun:

They [the CIA] held stuff back from the Warren Commission, they held stuff back from us, they held stuff back from the [1990s Assassination Records Review Board, or] ARRB. That’s three agencies that they were supposed to be fully candid with.

And now they’re taking the position that some of these documents can’t be released even today. Why are they continuing to fight tooth and nail to avoid doing something they’d promised to do?

Many wonder why, indeed.

It was against this backdrop that Kennedy, his wealthy background notwithstanding, proved himself a bold ally to ordinary people everywhere. Such an approach generated giant crowds wherever Kennedy went — including Dallas, on November 22, 1963. But it was not welcome in many quarters, especially not where money and power were concerned.

About the JFK Assassination Series

This series was inspired by an ongoing project of WhoWhatWhy Founder and Editor-in-Chief Russ Baker to produce a definitive, meticulous, book-length investigation of Kennedy’s death.

Click here for the introduction to the series. To see all the articles in the series, click here.

If you have information to bring to our attention about any aspect of the JFK assassination — or are with the media and interested in covering or reproducing our work or inviting Mr. Baker to appear on a program — please click here.

If you would like to be on a mailing list to receive news of the book, click here.