Principle can seem like a house made of straw in the midst of today’s political maelstrom.

|

Listen To This Story

|

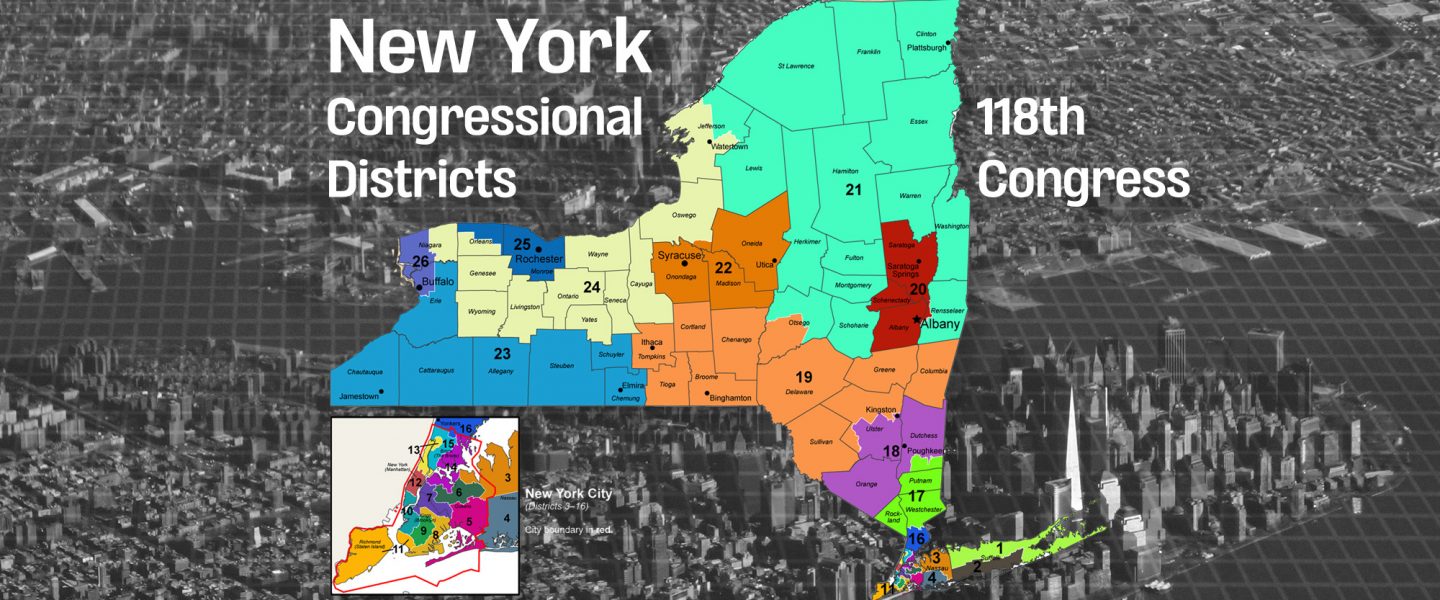

In 2022, the people of New York state were divvied up by a freshly gerrymandered districting map for the election of the state’s delegation to the US House of Representatives. The map was a product of the combined efforts of the Republican Party and Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo. The since-disgraced Cuomo preferred working with Republicans over his own party leadership, a problematic proclivity I examined last year.

Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing electoral maps to favor one party or the other. This often results in US House and state legislative districts of singularly weird shapes, designed to either “pack” the other party’s voters densely into as few districts as possible or “crack” (i.e., break up) their enclaves to keep them from being a voting majority in as many districts as possible — or both.

Now practiced with the aid of big data and powerful computers, it has become possible to redistrict more precisely and ruthlessly than gerrymandering’s founding father, the Colonial era’s Elbridge Gerry, could have imagined in his wildest dreams.

New York is a deeply blue state these days, with a Democratic trifecta (control of both state houses and governorship) since 2019. In 2020, the breakdown for the New York delegation to the US House was 19D-8R. In 2018 It was 21D-6R. In 2022 the aforementioned unfavorable map (and lackluster performance by the leadership of the New York Democratic Party) led to a disastrous 15D-11R result.

Rube Goldberg Would Be Proud

This map came about after the NY Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, threw out a map drawn up by the Democrat-controlled Legislature and a court appointee drew up a new map. At the time the court had a conservative majority, which was duly reflected in the leaning of the individual it appointed.

How did a Democratic governor and Democratic Legislature end up with a conservative court? It was the result of Cuomo tacking to the right and preferring to make deals with Republican leadership rather than with the New York Democrats.

The bottom line of of this seemingly parochial turn in intrastate politics was a shift of a few seats that arguably cost the Democrats control of the US House of Representatives and gave rise to the speakerships of first Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and then Mike Johnson (R-LA); powerful committee chairmanships for the likes of Jim Jordan (R-OH) and James Comer (R-KY); the blockage of the first meaningful border legislation in decades; the abandonment of Ukraine; the impeachment of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas; the efforts to impeach President Joe Biden; and the general do-nothing-constructive circus that the House has become under GOP control.

This was certainly bad from a Democratic perspective. But the 2022 map, like pretty much all gerrymanders, was also bad from a democratic, or pro-democracy, perspective.

Gerrymandering effectively allows parties to choose their voters rather than voters choosing their parties. And it tends to produce a plethora of “safe” seats, where incumbents’ only real concern is getting through the primary — which in turn results in catering to their parties’ most extreme elements, and the kind of hyper-polarization that has plagued our representative bodies of late.

It also means most voters don’t get to vote in meaningful, competitive legislative elections, with control of the 435-member US House, for example, coming down to perhaps 20 or 30 competitive elections for the smattering of “unsafe” seats.

But, while upholders of principle might complain about maps such as the NY conservative court imposed — not to mention the more extreme examples the parties in control have rammed through in numerous other states — leave it to the paladins of partisanship to strike them down and replace them.

To wit, the partisan balance of the NY Court of Appeals underwent a change. Two new progressive judges appointed to the state’s highest court by new Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democratic protege of Cuomo but more willing to work with her own party, came to the rescue and the Republican map was tossed out. The task was reassigned to the independent bipartisan commission created in 2014 by a constitutional amendment, which produced a map that was modestly more favorable to Democrats than was the one that cost them several seats in 2022.

Now the Democrats, who won a state legislative supermajority in 2022, have rejected this map as not being favorable enough. This strikes me as hypocritical.

Bringing a Gun to a Gunfight?

Am I being too hard on the Democrats here? It is no secret that Republicans have used technology to gerrymander the stuffings out of US elections across the country. Republicans in general in the past two decades have embraced being a minoritarian party, having lost the popular vote in every presidential election except 2004 but still winning the White House in 2000, 2004, and 2016, and fashioning — with a controversial assist from then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) — a highly partisan far-right Supreme Court supermajority (which, on cue, effectively greenlighted partisan gerrymandering in its 2019 Rucho decision, disingenuously leaving it to the legislatures to stop gerrymandering their own members into safe seats and majorities into perpetual power).

Republicans have also been more successful than Democrats at the gerrymandering game, in part because it’s easier to crack and pack densely populated urban and suburban centers than more diffuse rural areas, and in part because they beat the Democrats to the punch in their embrace of high-tech tools. So in GOP-controlled states like Ohio, Georgia, Florida, Texas, and Wisconsin, both US House delegations and state legislatures have been far more Republican than looking at the statewide vote margins would suggest.

And of course, the GOP also benefits from other legs up, such as the anti-democratic (and anti-Democratic) nature of the Senate, where the people of Wyoming enjoy about 67 times the per capita representation as Californians, and where half the country’s population is represented by 83 senators, the other half by 17.

And, as noted above, the Electoral College serves as yet another thumb on the electoral scales for the Republicans. It all adds up to a self-reinforcing rule, if not tyranny, of the minority — and, it would seem, a country in deep trouble.

If the Dems said they didn’t like partisan maps out of principle, then they should go with the bipartisan map they said they wanted. They could have campaigned on “if Republicans like gerrymandering, just wait till they see the maps we draw when we win.” They didn’t.

In light of which, is it reasonable to suggest that New York’s Democrats should be satisfied with winning an independent and bipartisan map rather than drawing a highly partisan map of their own? Framed another way, if Republicans in a state like Georgia are engineering a 9-to-5 House majority out of an essentially even statewide vote because they can, why should Democrats in New York, now that they can, tie their hands behind their own back?

What Price Principle?

In many ways this is a process versus outcome debate. Do we want a fair process in New York even if that leads to an unfair or undesirable outcome? I argue yes; my editor disagrees, maintaining that, in this political environment, New York’s Democrats might be guilty of dereliction of their duty if they didn’t gerrymander. We both agree it’s a debate worth having and not easily resolved.

I think the Republican use of gerrymandering, especially throughout the South, has verged on criminal. They have even repeatedly defied Supreme Court orders (a practice I might not mind if exercised for some progressive causes). Since Democrats don’t have the capacity to win a majority in most southern state legislatures, the only path for fairness must be imposed by an outside force.

Nor can we ignore the pragmatic reality that what really counts is aggregate control of the House, which is so evenly divided that one state party’s decision may well tip the balance — not to mention that the House elected this November, because of the presence of third-party candidates and the quirks of the 12th Amendment, may wind up choosing the president in what is known as a “contingent election.”

So the principle that politicians shouldn’t get to draw districts that are favorable to them, for all its unassailable rectitude, is not cheaply embraced. Should we therefore give it up? I don’t know. Given what’s at stake, adherence to principle may be a big, perhaps even an unrealistic, ask.

But striving for fair process against the proclivities of human nature is the essence of democracy. And I think we should at least hold people to their stated goals.

If the Dems said they didn’t like partisan maps out of principle, then they should go with the bipartisan map they said they wanted. They could have campaigned on “if Republicans like gerrymandering, just wait till they see the maps we draw when we win.” They didn’t.

They have what they asked for and now are behaving like a child who wants a newer, shinier toy. They should be called out for this pivot, just as when Republicans got their long-stated goal of overturning Roe and sending abortion to the states and promptly started aggressively advocating for a federal ban.

Getting what you wanted and then wanting more is a universal human condition, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t call out the hypocrisy. And if you campaign on a principle, then there should be political consequences if you subsequently abandon that principle. At least if we’re still in pursuit of a political society that isn’t purely “might makes right.”

In 2016, McConnell (who, after so much damage done, has promised to step down as GOP Senate leader, having surrendered control of his caucus to Trump) denied even hearings to Barack Obama’s SCOTUS nominee, Merrick Garland, because it was an “election year” — and then rammed through Donald Trump’s nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, when early voting in the 2020 election had already started. He tried to justify this with made-up history, but it was purely and obviously this kind of “because we can” politics.

Two-thirds of the Democratic-controlled Legislature in New York have voted to set aside the map from the redistricting panel. They have also passed a restriction on legal challenges to just four districts, in order to prevent the forum shopping that initiated the judicial challenge that led to the court-imposed map in 2022.

Forum shopping is where a litigator can pick a court that is very likely to give them the result they’re looking for. This is why so many lawsuits are brought by Republicans in the heavily partisan Fifth Circuit or why Donald Trump went to Aileen Cannon when he brought a challenge to the warranted search of Mar-a-Lago in his classified documents case. (This is the intervention in 2022 as opposed to the now ongoing criminal case that led to Cannon’s assignment through normal processes.)

The limit on forum shopping is to me the most sensible part of the New York Legislature’s move, though there are threatened challenges to this as well. It seems like the drama in the redistricting maps of New York is as endless as that of your average daytime soap opera. And just as with a soap opera, I am hooked to see what happens next.

With Our Future in the Balance, Not an Easy Call

This is the nationwide political problem writ small. There is an existential question of whether our political system can survive if Democrats are fighting for equality, as in rules fair to both sides, while Republicans seek to maximize political advantage on every lever of politics.

Is there any perfect process that works without good-faith effort from both sides? Possibly not. But for most of US history, certainly in living memory, there was a kind of faith in the swinging political pendulum, and acceptance of the basic dynamic that your side could expect to rule today or rule tomorrow but not both.

Perhaps that changed around the turn of our century, when Republican operative Karl Rove began talking about a permanent Republican majority, a quest for perpetual rule. Our politics seemed to veer in an existential direction, a trend towards all-or-nothing political armageddon fervently embraced and dramatically exacerbated by Donald Trump and his MAGAs.

In some crucial ways the warfare has been asymmetrical. On a national level the Democratic-controlled Senate’s refusal to consider expanding the Supreme Court or ending the filibuster — refusals that stand as hallmarks of unilateral political self-restraint — may have doomed important components of Biden’s agenda, and led to the loss of women’s reproductive rights, the failure to protect voting rights, and a host of other disastrous outcomes that have left our democracy teetering on the brink.

Principle can seem like a house made of straw in the midst of such a maelstrom.

On the other hand, holding up independent redistricting is either an important principle or it’s not. And if the Democrats in New York long embraced it as a defensive bulwark, it must be noted when they abandon it when it becomes more conveniently self-serving to do so.

Doug Ecks is a lawyer and writer. He holds a JD from the University of California, Hastings and a BA in philosophy from California State University, Long Beach, Phi Beta Kappa. He also writes and performs comedy as Doug X.