Move Fast and Break Skulls?

A whistleblower is “flabbergasted” by the FDA approval of Elon Musk’s brain-chip implant startup Neuralink as animal abuse allegations remain unanswered.

|

Listen To This Story

|

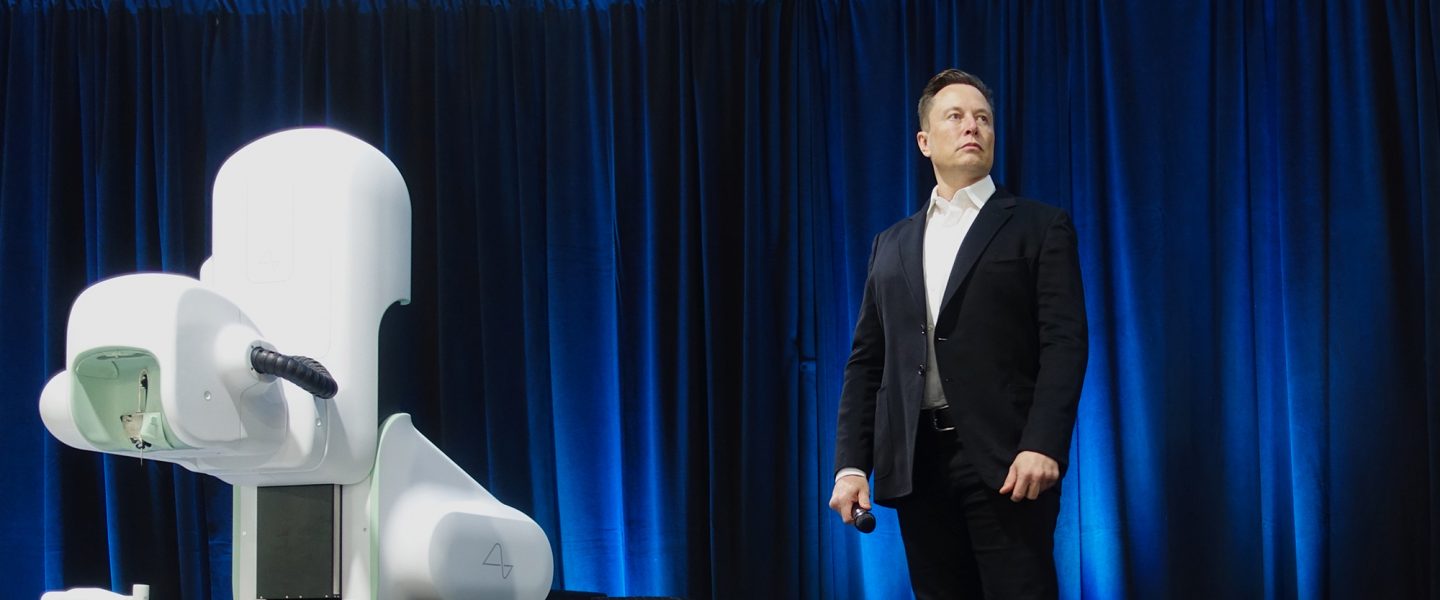

On May 26, Elon Musk announced on his social platform Twitter that his other, less-famous company Neuralink received permission to start clinical trials of its brain implant devices from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This means that Neuralink will soon be inserting devices into the skulls of willing human subjects — as opposed to the highly controversial animal trials that the company performed over the past five years. Neuralink has been registering patients with quadriplegia, paraplegia, vision loss, deafness, or aphasia in the last year, but has kept quiet about when trials are expected to begin.

On Twitter — which serves as Musk’s digital town hall and megaphone — thousands of fans and skeptics reacted to Neuralink and Musk’s tweet about the FDA clinical trial approval with a mix of adulation, horror, and cynicism. Some Twitter users weighed in about Neuralink’s potential to do everything from curing Parkinson’s Disease to supercharging brains with ChatGPT. Supporters like KrakenNFT tweeted in jest: “Boutta get my NFT wallet hardwired into my brain.” Others, like “Pope of Muskanity,” congratulated Neuralink and inquired about the technology’s applications for mental illness: “How would you treat schizophrenia using Neuralink?” Others were more suspicious of the entire premise of brain implants altogether: One user compared Musk to Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos. A user named Becky tweeted: “You honestly think this is good for humanity? Asking for my soul???”

Meanwhile, a mini-culture war raged in response to an article that a user posted beneath Musk’s FDA approval news tweet that featured a photo of a small pitiable monkey and the headline: “Elon Musk’s Neuralink has reportedly killed 1,500 animals in four years,” citing a report from Reuters about the company’s botched device implant surgeries performed on sheep, pigs, and monkeys in haste due to pressure from company leaders to get to market quickly. (The accusations ultimately led to a federal USDA probe on violations of the Animal Welfare Act.)

“That is quite an unusual number of large animals to sacrifice in a small amount of time,” said Dr. Vivek P. Buch, a neurosurgeon and assistant professor of neurosurgery at Stanford who’s worked with nonhuman primates (monkeys) in his research. Buch should know; he counts among his mentors and colleagues two pioneers of brain-computer interface (BCI) technology: Dr. Krishna V. Shenoy and Dr. Jaimie Henderson, neurosurgeons who made headlines in 2021 when they gave a paralyzed man the ability to write text using his thoughts with the help of two brain implants.

“In some ways they [Neuralink] are many years behind the researchers in this field, but I think Elon has a sort of an uncanny ability to get a lot of press for anything he does, so he’s brought a lot of publicity to the field,” said Buch. “But the actual tech itself is a lot of the work that BCI pioneers did already.”

Buch said that the milestone that Neuralink has publicly touted to date — teaching a monkey to play the video game Pong using its mind (which went viral in a video in 2021) — was already available more than two decades ago — and didn’t require invasive brain implants.

Last fall, Musk asserted in a recorded show-and-tell broadcast on YouTube that Neuralink’s technology could restore vision in blind people. “Even if someone has never had vision ever, like they were born blind, we believe we can still restore vision,” Musk said, without providing evidence of the phenomena beyond demonstrating how the brain implant can stimulate a flash of light in a monkey’s brain. Another demonstration showed how electrodes inserted into a pig’s spinal cord could control its leg movements by allowing the brain and limbs to communicate, which Musk presented as early evidence for the technology’s capability to restore mobility in people with debilitating conditions.

However, according to a former Neuralink employee, who spoke to WhoWhatWhy on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution from what he called “Musk fanboys who tend to be conspiracy theorists that believe in his cult of personality,” Neuralink’s implanted brain device were unnecessarily invasive and led to numerous deaths through at least 2021.

“It was a one-way entry: You couldn’t get it out without damaging the brain, so I’m curious if they ever figured out the design,” said the whistleblower, who worked on multiple lab necropsies — the animal equivalent of autopsies. “I want to know what they actually presented to the FDA for approval, because if it’s anything like what I saw when I worked there, then I’m flabbergasted.”

The whistleblower was privy to details of several of the necropsies noted in a highly publicized lawsuit filed by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) against Neuralink to obtain information about invasive and deadly brain experiments on 23 monkeys between 2017 to 2020. (PCRM is a nonprofit organization made up of over 17,000 physicians that works to find alternatives to the use of animals in medical education and research.)

It’s worth noting that while news outlets deconstructed the more than 700 pages reporting on Neuralink’s Animal Welfare Act violations in February 2022, Musk avoided responding to the press and instead posted images of SpaceX rockets and Hitler memes mocking Justin Trudeau for Canada’s COVID-19 vaccine mandates on Twitter — an approach that helped him redirect attention to the story.

According to files reviewed by PCRM, Neuralink’s “rushed” and “sloppy” brain surgeries entailed drilling holes into the monkeys’ skulls, and attaching devices and probes to the brain using a “bioglue” that wasn’t approved by the FDA. These procedures and materials led to acute brain damage, vomiting, seizures, paralysis, bacterial meningitis, and physical collapse after many of the devices became sites of infection.

PCRM’s reports show that Neuralink staff violated industry protocol by delaying euthanizing monkeys suffering from gruesome brain injuries for days and sometimes weeks after it was apparent that their injuries were fatal.

“It’s not easy to admit failure when 19 of the 22 board members, who are supposed to be overseeing animal welfare, are all employees who want to please one person,” the whistleblower said. “I think we didn’t get shut down then because it was Elon, and he’s the richest guy in the world.”

Attempts to reach Neuralink were unsuccessful by phone, email, and at the company’s Fremont, California headquarters, where on July 21, 2022, windows were surrounded by a dormant construction zone and guarded by a security officer. I reached out to Synchron and Paradromics, competitors working on similar technology that have received approval for clinical trials prior to Neuralink. They didn’t respond.

We confirmed the FDA’s clinical trial approval with a spokesperson; however, she didn’t comment on the number of animals “sacrificed” (the official term for euthanizing an animal after an experiment is completed, or fails). Nor could the spokesperson provide the details of Neuralink’s animal testing data because that “would be considered commercial confidential information.” The spokesperson added that the FDA approves trials of devices like Neuralink’s brain implant if potential benefits “outweigh the risks, and if remaining risks have been appropriately mitigated.”

One former employee who worked as an engineer at the company in its early days told me that he wished he could “live in a fucking Neuralink monkey penthouse,” albeit he admitted that everything he knew about the monkeys was from the company’s promotional YouTube posts featuring the animals’ relatively posh living quarters.

Internally, there was a wide disconnect between the scientists and engineers at Neuralink, according to the whistleblower. He said that engineers who implanted the devices didn’t understand biology and treated the brain like a “rigid instrument,” rather than an organ that floats in the skull, and that the electrodes were being built by materials engineers with little input from the neurosurgeons.

“People start with good intentions and I don’t think anyone is a horrible person who enjoyed torturing these monkeys and pigs,” said the whistleblower. “But at a certain point you can talk yourself into doing the wrong thing when there’s a chance you’ll make a lot of money or when a someone with Elon Musk’s charisma tells you that ‘You can change the world,’ so who cares if you kill a bunch of animals — ‘Ya eat bacon, dontchya?’”

Ryan Merkley, director of research advocacy at PCRM, refers to Neuralink’s current mission as “altruism washing,” adding that Musk’s original mission was to achieve symbiosis with AI when he spoke about the technology in 2019 during the company’s launch event because of his professed fear of the singularity — a hypothetical future in which humanity merges with computers. (Musk has maintained that the singularity is akin to “summoning the demon” while inventors like Ray Kurzweil say it will benefit humanity by exponentially improving brain computing power.) “The irony is that [Musk is] developing the most complex AI platform while saying he is concerned about the speed at which AI is developing,” said Merkley.

The whistleblower added that it was known internally that Musk drew fears of an AI takeover from science fiction stories in which a super intelligent technology takes over the world and turns people into pets. “At some point Musk decided that if you can’t beat them, join them,” Merkley said, adding that he believes that Musk meant well and eventually understood the more practical applications for the technology, but that his intentions were poorly executed because of his “cult of worshippers that made accountability and scientific progress difficult.”

Even on Twitter — where neuroscientists and researchers abound and share knowledge freely — Neuralink follows just one person: Elon Musk.

Despite his online deification, Musk couldn’t answer questions from junior staff about Neuralink’s technology at a company all-hands meeting three years ago. According to the whistleblower, the billionaire brushed off a fairly simple biology question: “I pay other people to worry about that for me.”

After that, the whistleblower says that he and most of his colleagues left the company, most notably former Neuralink co-founder Max Hodak, who went on to found his own BCI company.

“I asked if we were making progress and wondered what was the point of all of these animals suffering,” the whistleblower said. “It was hard to continue because when you strip away their exterior skin, monkeys look completely human.”