For Christians Worried About AI, the Devil Is in the Data

Secular concerns about AI-generated art end when you die. With Christians, it’s more complicated.

|

Listen To This Story

|

For the secular… for the profane… for the fallen… artificial intelligence is a harbinger of a lifestyle change. It threatens the movies, it threatens the demos, it threatens the precious workflow. But for the Christian, AI is nothing less than a crisis of the spirit.

The big story we’ve heard lately is about “Shrimp Jesus,” an AI-generated figure composed of crustaceans. This avatar, and related oddities, clogged Facebook in the past few months with wildly viral posts. 404 Media’s Jason Koebler reported on the situation, wherein “hundreds of AI-generated spam pages are posting dozens of times a day and are being rewarded by Facebook’s recommendation algorithm.”

Spam or scam, the Jesuses seemed to be proof of what’s called the dead-internet theory: Bots interacting with other bots, self-perpetuating and perfectly happy to evolve in a senseless hellscape of content inhospitable to humans. This reads like anthropocentric cynicism, where if it ain’t human, it must not be good. I like to think of the bots that perpetuate Shrimp Jesus as digital extremophiles, similar to the bacteria that thrive on the superheated volcanic vents at the bottom of the ocean. It’s not for us, but it seems to be having a good time.

That story, which was everywhere, might seem at first blush to be about AI and religion. It’s not, though; it’s about the malfunctioning of platforms. (Jesus isn’t used here for any kind of spiritual or political commentary, but only because his well-known image is primed for viral distribution.) But there’s another story that gives us a glimpse of the difficulties faced by the faithful.

In April, a Christian group called Catholic Answers launched an animated chatbot called “Father Justin” that answers, you know, Catholic questions. Since a popular online pastime is breaking chatbots, people lobbed all sorts of things at the robo-cleric. Father Justin, predictably, went sideways — absolving sins, approving the use of Gatorade for baptism, and claiming to live in Assisi, Italy. Religion Unplugged pointed out that we’ve been here before:

Nothing that happened during this cyber drama would have surprised anyone who paid close attention to the complex high-tech questions that surfaced in ancient faith traditions during the coronavirus pandemic, such as: Does watching an online Mass count as attending Mass?

The outlet then weighed in on the theological implications:

Creating digital “persons” is going to challenge “what Catholics believe technology can do and can’t do,” said Brett Robinson of the McGrath Institute for Church Life at the University of Notre Dame. “When you start debating what is ‘embodied’ and what is ‘disembodied,’ that takes us straight into questions that are going to make us uncomfortable. … Catholicism is an incarnate faith, and there’s no way around that.”

Robinson went on to say that “if you feel anxious about talking to a real priest, then that kind of human contact is precisely what you may be trying to avoid. Can you solve that problem with an app?”

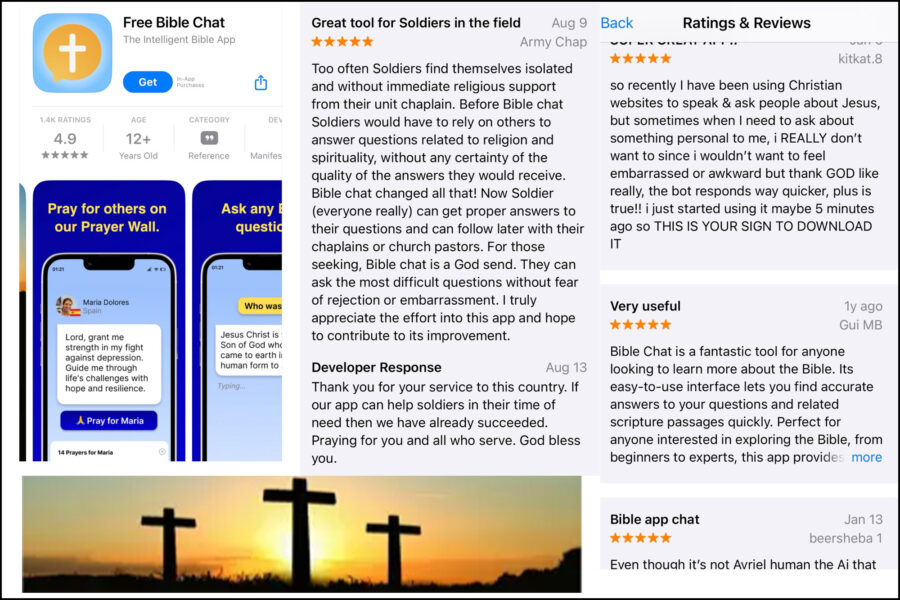

App developers think you can. Peruse the Sodom of the App Store and you’ll find multiple offerings that have run the text of the Bible through a large language model, so that the spiritually curious can ask questions and get, apparently, satisfying answers. (You can also submit prayers, or pray for others with a single click.) To judge from the comments in the App Store (take with a grain of salt), users get “clear concise answers that are backed by scripture.” Interestingly, some reviewers say they like that the chatbot will answer questions they feel too “awkward” or “embarrassed” to ask a person, which puts Robinson’s concern about “human contact” being “precisely what you may be trying to avoid” into sharp relief.

How to use artificial intelligence to augment a spiritual journey? This has become a core question for the faithful. Pope Francis, himself no stranger to AI-generated art, addressed the use of artificial intelligence in a January message:

The rapid spread of astonishing innovations, whose workings and potential are beyond the ability of most of us to understand and appreciate, has proven both exciting and disorienting. This leads inevitably to deeper questions about the nature of human beings, our distinctiveness and the future of the species homo sapiens in the age of artificial intelligence. How can we remain fully human and guide this cultural transformation to serve a good purpose? …

Human beings have always realized that they are not self-sufficient and have sought to overcome their vulnerability by employing every means possible. From the earliest prehistoric artifacts, used as extensions of the arms, and then the media, used as an extension of the spoken word, we have now become capable of creating highly sophisticated machines that act as a support for thinking. Each of these instruments, however, can be abused by the primordial temptation to become like God without God (cf. Gen 3); that is, to want to grasp by our own effort what should instead be freely received as a gift from God, to be enjoyed in the company of others.

Christian anxiety about AI is an analog to good-old secular anxieties — same worries about how the technology fits into our lives, about what it might replace, about whether and how we retain our humanity. But unless you’re religious (or reading Christian media), you’re probably not seeing the way the conversation plays out in Christian circles. That rhetoric doesn’t show up in the mainstream… though I would love to see tech bros under the hot lights of some Congressional subcommittee fielding queries from senators about “the primordial temptation to become like God without God.”

Not for nothing, but Martin Luther was uneasy about his era’s paradigm-shifting technology, too. Christian scholar David Bagchi writes that while “Luther once famously hailed printing as ‘the latest and greatest gift, by which God intends the work of true religion to be known throughout the world and translated into every tongue,’” he also

had a notoriously ambivalent attitude towards what was still the new technology of the printing press. He could both praise it as God’s highest act of grace for the proclamation of God’s Word, and condemn it for its unprecedented ability to mangle the same beyond recognition.

You, like me, may find it interesting that, aside from the odd robot priest, AI text doesn’t seem to stir up as much controversy among Christians (the word isn’t The Word) as AI-generated images.

High-octane AI-art generators like Midjourney have made it possible for users to create images of a Jesus Christ who is far, far more of a snack than the one in the old portrait that Baptist grandmothers kept uncomfortably close to their bedsides. These are not the Shrimp Jesuses, Lord God of Facebook bots, but rather a modern incarnation of pious art. They’re all over Instagram and X and TikTok, along with other Biblical scenes that are designed as spectacle — less Charlton Heston and more King James Cinematic Universe.

On TikTok and Instagram, an account called The AI Bible presents the Good Book as Summer Blockbuster. It also cleverly nods to what you might call the limitations of human imagination, or just the inertia of tradition, when it compares “what people think” something looks like (the Transfiguration, Moses talking to God) with how the Bible describes it. There’s a whole series depicting how Ezekiel describes the appearance of angels… which, quick Sunday School lesson:

Ezekiel 10:9-10

I looked, and I saw beside the cherubim four wheels, one beside each of the cherubim; the wheels sparkled like topaz. As for their appearance, the four of them looked alike; each was like a wheel intersecting a wheel.

Ezekiel 10:12

Their entire bodies, including their backs, their hands and their wings, were completely full of eyes, as were their four wheels.

Verily, the AI Bible hath generated what commenters call “Biblically accurate angels” as clusters of eyeballs and interlocking golden rings and orbs and feathers and something like celestial barbed wire.

@theaibibleofficial Biblically Accurate Angels pt. 2 Ezekiel 1 and 10

Somewhat less epic is the output from an app called BiblePics. In its Selfies gallery, there’s Abel snapping his final moments as he runs from Cain. There’s Jesus and the gang at dinner, possibly, one feels, the last time they’ll all see each other for a while. Because sure enough, here’s one of Jesus carrying a (misshapen) cross to his crucifixion. And then there’s a “Bible cookout,” which is about what you’d imagine (“Jesus and his disciples fire up the grill”).

Frankly, I can’t tell if this is a joke or what.

An August 2023 article in The Jerusalem Post talks to the Israeli creator of BiblePics: “Sinai Elihai, an esteemed former Googler, growth marketing adviser, and proud father,” who after talking to his young son about the Bible’s “lack of visual appeal and lengthy text,” created a platform “to let Gen Z ‘Binge the Bible.’”

On X, people scoff and argue about the spiritual morality of AI art: “AI is categorically unable to create sacred art under the influence of grace, which can be quite dangerous,” says one user; “AI is not satanic, it is not a living being and it is not subject to Satan’s deceptions. While there are valid arguments against this statement, one must consider the good christian art it produces,” says another.

I’m swayed by the perspective of Atlanta-based illustrator Ross Boone:

One way Christians have historically interacted with art is through a spiritual practice called Visio Divina. This practice is an opportunity to invite God to speak to us by contemplatively listening to what he is saying while looking at an image. In my own experience, I’ve found that looking at AI art in this way is capable of moving me and evoking a response from me in ways that traditional Christian artwork and depictions of the Bible haven’t.

(Has he seen the crucifixion selfie?)

I usually have an idea of what I might see when I type Biblical themes into the AI generator, but I’m often driven to awe and wonder when the software renders images I hadn’t fathomed myself.

Catholics seem — seem; this is anecdotal — to be the most consistently resistant to AI-generated imagery, or at least less enthusiastic about the power of computers to render endless square-jawed Jesuses who are absolutely shredded.

The National Catholic Register, for one, leans toward the primacy of human artists, asking “Why is one far superior to the other?” The outlet quotes Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs, who is (per her website) “a sacred artist in the perennial Western tradition”:

Sacred art is not a composite of popular images on the subject. Sacred art is the work of a trained artist cooperating with the grace of inspiration to create a visual description of a supernatural reality. Machines are purely material and therefore cannot respond to the challenge of communicating a supernatural reality with visual metaphor.

Where the biggest secular concerns about AI include threats to democracy and workforce, Thompson-Briggs gives voice to an even older danger than job insecurity. “Allowing technology to have such a heavy hand in the creation of an image opens the door to influences beyond the sphere of the guiding hand and mind of the artist,” she told the Register. “It is reasonable to think that the demonic could use this as an opportunity.”

Kathleen Carr, president of the Catholic Art institute, doesn’t think AI-generated imagery is even art, “since it lacks a human’s imagination and hand in creating it.” Her indictment is total: “Artists mirror God by being co-creators, bringing beauty and order into the world in architecture, beauty and art.”

Meanwhile, Joshua Madden, a Catholic theologian at Oxford, goes farther, asking, “Is AI ‘Sacred’ Art Actually Sacrilegious?” He argues that it is:

The use of AI seems to fail to live up to the standard of Christian worship — that it be rational and spiritual; and to pass off the technologically synthesized conglomeration of colored pixels we might call “AI art” would be to offer artificial worship. Thus, using AI art in the context of prayer or worship would be unworthy of the act.

Pope Francis, for his part, doesn’t seem to come down that hard, evincing the sort of wisdom and balance that makes me hope he gets a dispensation to live forever. In his January message, he writes:

A century ago, Romano Guardini reflected on technology and humanity. Guardini urged us not to reject “the new” in an attempt to “preserve a beautiful world condemned to disappear.” At the same time, he prophetically warned that “we are constantly in the process of becoming. We must enter into this process, each in his or her own way, with openness but also with sensitivity to everything that is destructive and inhumane therein.” And he concluded: “These are technical, scientific and political problems, but they cannot be resolved except by starting from our humanity. A new kind of human being must take shape, endowed with a deeper spirituality and new freedom and interiority.”

I keep coming back to the concept of Visio Divina. I can’t speak to sacred art as inspiration from the divine, or AI art as a vehicle for demonic interference, but I have gazed upon the crazy swirling eyeballs and interlocking golden rings of The AI Bible’s angels and felt… something. Not the Presence that sacred art prescribes, but something more like absence — absence of the familiar, absence of easy meaning. That which destabilizes one’s conception of reality, that which short-circuits the connection between expected and realized.

Which sounds like an Eastern concept: emptiness. The sound of one hand clapping. The unhewn log. Kill the Buddha at the crossroads. But it also sounds like Romano Guardini and his “process of becoming.”

I don’t think that AI art is the empty vessel, exactly. But maybe it’s worth contemplating these strange unpredictable nonsensical creations of ours, if for no other reason than it might finally bring us closer to God, who gets it.