The $30 Billion ‘Ike Dike’ Will Not Save Houston From Climate Change

The barrier — the Army Corps of Engineers’ largest project ever — may fail to block climate-fueled storm surge, and won’t prevent other urban flooding in Houston.

|

Listen To This Story

|

In September 2008, Hurricane Ike made landfall near Galveston, Texas, as a Category 4 storm with around 20 feet of storm surge. Even though the hurricane caused more than $7 billion in damage, it soon became clear that the disaster could have been much worse: If the storm surge had struck the coast at a different angle, water might have funneled up the Houston ship channel and inundated the city’s all-important petrochemical hub, not to mention thousands of homes.

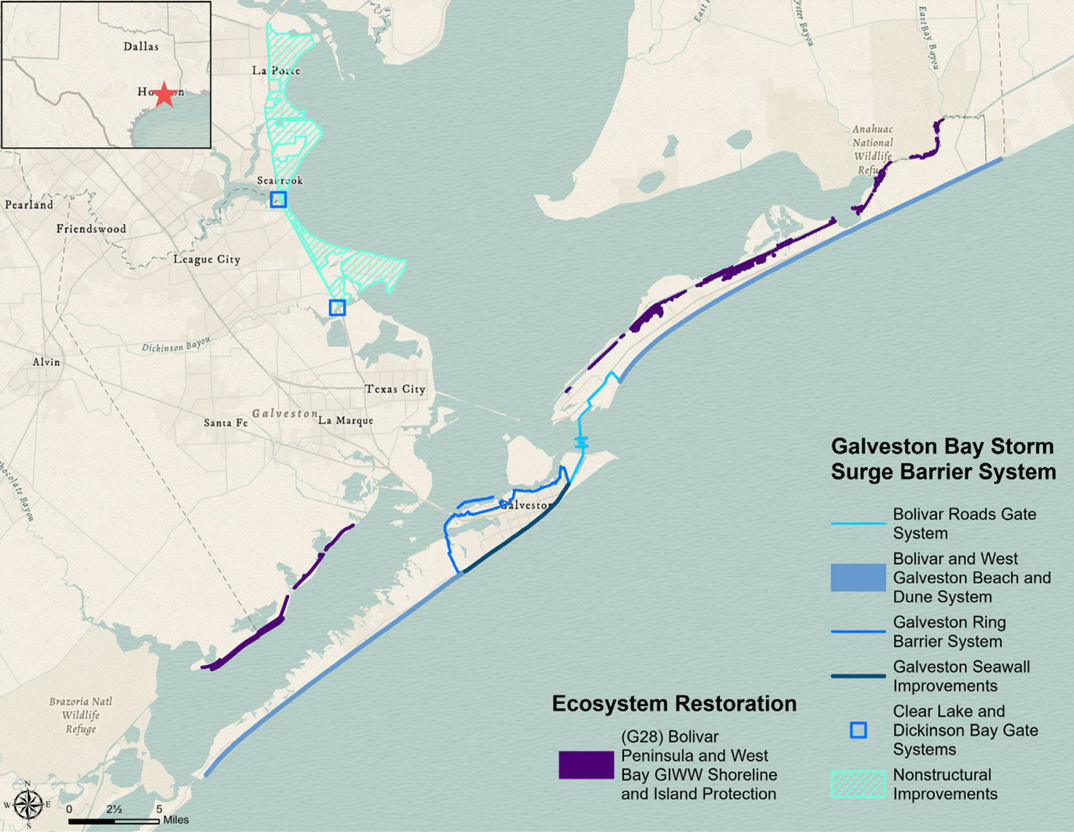

In the aftermath of the storm, Texas officials searched for a way to protect Houston from similar events in the future, and they soon settled on an ambitious project that came to be known as the “Ike Dike” — a chain of sea walls and artificial dunes along the 50-mile-length of Galveston Bay, anchored by a two-mile-wide concrete gate system at the mouth of the ship channel. The gate would stay open during calm weather to allow ships to enter and exit the channel, but would close during hurricanes, shielding the city and its oil infrastructure from flood events.

The Ike Dike has since become synonymous with hurricane resilience in Houston: Local officials have spent a decade lobbying for the project, and now it’s closer than ever to becoming a reality. The US Army Corps of Engineers, the nation’s chief builder of levees and flood walls, secured congressional approval to move forward with the barrier last year. The $31 billion system is the largest project that the Corps has ever undertaken, with the gate system accounting for two-thirds of the cost. The agency says it will take around two decades to complete.

Despite the massive scale of the project, there’s one big problem: Experts say the Ike Dike won’t reliably protect Houston from major storms. The barriers may not actually be tall or strong enough to handle extreme storm surge, especially as climate change makes the rapid intensification of hurricanes more likely. And even if the barrier does hold, it won’t do anything to stop the kind of urban flooding that occurred when Hurricane Harvey dropped 30 inches of rain on Houston in 2017. The Corps has long preferred to fight hurricanes with large coastal engineering projects, but such projects only protect against one type of flood risk.

Though the Ike Dike would be one of the largest hurricane defense systems anywhere in the world, the Corps’s own designs suggest it might not be able to handle storm surge from Category 4 and 5 hurricanes. The original Ike Dike concept was the brainchild of a professor at Texas A&M University, who proposed a series of 17-foot-high barriers that would ring the entirety of Galveston Bay, sealing it off from the Gulf of Mexico. Another group of experts at Rice University later proposed a complementary project that would line the interior of the bay with levees and artificial islands, providing a second layer of defense for downtown Houston.

The version that the Corps ultimately settled on is far less ambitious. Its dunes would only rise 14 feet high, lower than the peak storm surge during Hurricane Ike itself. The final design also leaves a hole on the western side of the bay where surge could enter uninhibited, and it doesn’t call for a second line of defense like Rice’s artificial island network; the agency considered both options but decided that they weren’t worth the money.

The reduced scale of the project means that bigger surge events could blow through the dunes or even overtop the central gates, pushing toward the city just as Hurricane Ike could have done. The Corps’s own analysis found that even with the project, the bay would still suffer an average of more than $1 billion in annual storm damage. And as sea levels rise, the barriers will grow less effective, ratcheting up the risk even more.

Experts say the agency likely downsized the Ike Dike to comply with a Reagan-era regulation designed to limit federal spending. The rule requires the agency to conduct a “benefit-cost analysis” for every project it undertakes, ensuring that the project will prevent more dollars in future damage than it costs to build. But the Corps can only consider “benefits” that occur in the first 50 years after a project is built, and it couldn’t justify paying for full protection against large storms. The gate system might protect against a major 500-year flood event, for instance, but the dune barriers alongside it will only provide protection against a much smaller 50-year flood event.

The agency’s cost-benefit constraints mean that the Ike Dike won’t do much to protect Houston itself, said Jim Blackburn, an environmental lawyer who teaches at Rice University. Coastal communities like Galveston will get a lot safer, but the existential risk to Houston will remain.

“There will be some benefits to the ship channel [and Houston], but it only really goes until a certain size of storms,” said Blackburn. “There’s a new reality for the future, and the Corps is not as able to respond to that type of evolving risk.”

In response to queries from Grist, a spokesperson for the Army Corps of Engineers defended the Ike Dike project, saying it would reduce damage from medium-size hurricanes by as much as 77 percent and prevent an average of $2 billion in damages each year, though “residual risk” will remain.

“The investment [in the Ike Dike] pales in comparison to the hundreds of billions of dollars in devastation the Texas coastal communities would incur by a direct hit of one or more massive hurricanes,” the spokesperson said. “There is no other proposal which meets the federal government’s strict requirements, can be completed in the time frame proposed, [and] has Congressional approval.”

Even if the Ike Dike does become a reality, Houston is much further behind on addressing flood risk that doesn’t come from the Galveston Bay. When storms pass over the Texas coast, the rain they drop drains out into the Gulf of Mexico. As it moves toward the ocean, this water flows right through Houston along serpentine waterways called bayous. These bayous run past tens of thousands of homes, some of them mere feet from the water. The largest of them, Buffalo Bayou, passes right through downtown.

The Corps itself is to blame for some of the flood risk on Buffalo Bayou. Back in the 1930s, the agency tried to control flooding on the waterway by building two dry reservoirs that can trap water during big storms, holding it back from the city’s downtown. But the agency didn’t carve out enough land to store the water from a mega-storm like Harvey, and developers later built several subdivisions on land that the Corps knew would flood. When these subdivisions filled up with water during Harvey, homeowners sued the agency for damages and won a settlement that could exceed $1 billion.

Even as it moves forward with the Ike Dike, the Corps is looking for a way to control this urban flooding as well, but it doesn’t have many good options. Its initial proposals to line Buffalo Bayou with concrete and build a third dry reservoir on the open prairie outside Houston fell apart amid concerns about environmental impacts. The agency’s other big idea, which has garnered some support from Houston-area flood officials, is to dig a giant stormwater tunnel between the flood-prone city and the Gulf of Mexico, funneling excess water underground before it can inundate urban Houston. But this project, too, faces significant challenges: The tunnel system would cost as much as $12 billion and would take more than a decade to build.

The Corps’s projects also neglect the city’s other bayous, most of which run through Black and Latino neighborhoods, according to Susan Chadwick, the director of Save Buffalo Bayou, a local environmental nonprofit. Chadwick argues that the agency should spend money on grasslands and green spaces that can soak up water across the city before it ends up in the bayous in the first place, rather than trying to control those waterways with engineered “gray infrastructure.”

“We believe in stopping stormwater before it floods the streams,” said Chadwick. “We need to focus on slowing and holding water where it falls, and we need more individual and community efforts to stop and slow and spread out and soak in stormwater.”

The Corps doesn’t tend to fund that kind of green infrastructure, Chadwick said, and disadvantaged neighborhoods often lack the political clout to advocate for major federal infrastructure investments. Houston and surrounding Harris County have raised some money for local flood-control projects, including through a 2018 bond issuance, but without federal dollars it will be hard for the city and county to keep up with the risk. (The Army Corps of Engineers did not respond to questions about its inland flooding projects before publication.)

Houston is not the only place where the agency has proposed to mitigate hurricane risk with ambitious engineering projects. Corps officials have pitched large sea-wall structures to several other cities that are vulnerable to hurricanes and storm surge, including Norfolk, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina.

In some cases, locals have spurned the agency’s projects for being too expensive or harmful to the environment. Officials in Miami recently rejected the Corps’s plan for a wall that would have blocked ocean views, and environmentalist groups in New York torpedoed plans for a five-mile gate structure that would have spanned the 10-mile bay between Long Island and the Jersey Shore. The Corps returned to New York last year with a $52 billion plan to build 12 smaller gates, but the same groups have rejected that plan as well, saying it still focuses too much on storm surge rather than on sea-level rise and neighborhood flooding.

Texas has gone the opposite route, embracing the Corps’s focus on gray infrastructure. As Blackburn sees it, those projects will leave Houston a long way from solving its hurricane woes.

“Houston is an engineering town, and this is a big-time engineering solution,” he told Grist. “But I think what you see is an agency that’s working with concepts from the 1980s facing 21st-century flooding problems.”

This story by Jake Bittle was originally published by Grist and is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.