Drought Leads to More Fossil Fuel Emissions

Hydropower lost in one area is often replaced by fossil fuel power produced elsewhere — and renewable energy sources may struggle to meet electricity demands caused by more frequent dry spells.

|

Listen To This Story

|

Drought reduces hydroelectric power generation in the western United States, and fossil fuel–based plants in neighboring areas pick up most of the slack.

According to new research, increases in the burning of fossil fuels during droughts place a greater environmental and health burden on communities near fossil fuel–based power plants, which may not be affected by the actual drought. The price of drought, the scientists said, exceeds the cost of lost hydropower.

What’s more, future renewable energy scenarios might not meet electricity needs during droughts, said Minghao Qiu, lead researcher on the study and an Earth system scientist at Stanford University in California. “Maybe in a normal year, renewable energy will generate more than 80 percent of our electricity,” he said. “But under drought, when we need some additional source to cover our electricity gaps, those energy scenarios project that we’re going to be heavily reliant on fossil fuels.”

Carbon Fills the Gaps

As anthropogenic climate change warms the planet, drought-prone areas have experienced longer and more frequent dry spells. Reduced precipitation means less water flowing through hydroelectric power plants and less energy generated from hydropower. Previous studies have found that extreme events, such as the one that struck California in 2012–2016, can cost consumers $0.5–$1.5 billion per year.

Residents’ energy needs don’t just disappear during a drought — in fact, they sometimes grow.

But residents’ energy needs don’t just disappear during a drought — in fact, they sometimes grow, as dry conditions can be coupled with heat waves that make people crank up their air-conditioning. So which energy sources replace the lost hydropower, who produces that energy, and what does it cost residents?

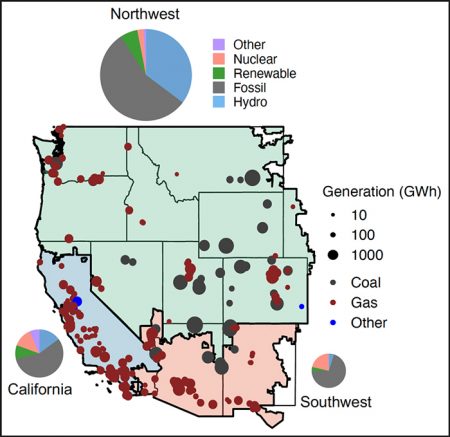

To answer these questions, the researchers gathered archival data on drought, power plant energy generation, and carbon emissions in the western United States over the period 2001–2021. They split the region into three areas — northwest, southwest, and California — to examine how energy production and carbon emissions changed in each area during times of drought, even if a drought occurred in a different area.

Fossil fuel power plant generation increased by up to 65 percent relative to nondrought periods, Qiu said. This was primarily because power from fossil fuel plants replaced hydropower lost to drought. Fossil fuel plants can ramp up production more quickly than renewable sources can.

Yet fossil fuel generators need water, too, as part of their cooling process. The lack of available water means that even these plants are not running efficiently, so even more fuel is needed to produce the required energy. Drought-induced heat waves and wildfires might also affect the efficiency of power plants with solar or wind sources; fossil fuels might need to make up for that lost energy, too.

The team found that more than half of the increased fossil fuel burning takes place outside the drought-stricken region. This is explained by the interconnected power network, which allows nearby areas to ramp up their power generation and export that electricity to the drought-affected area. Qiu explained that under normal conditions, for example, the northwest exports hydropower electricity to California and the southwest. But during an extreme drought, the northwest can’t export as much energy to the other two areas.

“Therefore, [during a drought in the northwest,] California and the southwest need to find additional electricity sources to cover their demand,” he said. “And what we find in historical data is they ramp up their own fossil fuel power plants.” The resulting increase in carbon emissions worsens air quality and puts people’s health at risk beyond a drought’s boundaries.

The team found that about 12 percent of total regional carbon dioxide emissions were drought induced.

The total health and economic price of drought-induced fossil fuel production was about 1.5–2 times the cost of the lost hydropower electricity, Qiu said. That amounts to about $20 billion over 2001–2021, in addition to the cost of lost hydropower. Roughly $14 billion (70 percent) of that is from carbon emissions, $5.1 billion (25 percent) is from emissions of small particulate matter (PM2.5), and $0.9 billion (5 percent) is from methane leaks.

The results were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Need for More Renewables

If climate change continues unchecked, severe drought will become more extreme and more frequent. The researchers examined an aggressive renewable energy transition scenario and found that the growth of renewables might not be able to keep up with the projected increase in drought and subsequent loss of hydropower.

“The study reinforces the conclusion that some of the worst impacts of climate change will be on water systems and highlights the close connections between water and energy,” said Peter Gleick, an expert in water resources management and cofounder of the Pacific Institute in Oakland, CA, a nonprofit research center. “Better, integrated management of water and energy systems together offers significant advantages in both mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to now unavoidable impacts.” Gleick was not involved with the new research.

“Some of the worst impacts of climate change will be on water systems.”

The findings are “highly transferable” to other areas of the world that rely heavily on hydropower and will experience future hydroclimatic change, said Jordan Kern, an environmental scientist at North Carolina State University at Raleigh who was not involved with the study.

“For states and regions that are currently dependent on hydropower … persistent vulnerability to drought will make it more difficult to decarbonize the grid and, by extension, other parts of the economy,” Kern explained.

“In particular,” Kern said, “power system planners will have to build in an expectation of drought … in the design of future, decarbonized power grids. This means building extra capacity of another kind, which could be fossil fuel related or not. Bottom line: this will add an extra financial cost for consumers.”

“Power system planners will have to build in an expectation of drought … in the design of future, decarbonized power grids.”

The current reliance on fossil fuels as a backup energy source is troubling, Gleick said, but some Western states have already made strides in developing more renewable energy sources to compensate for drought-related drops in hydroelectricity.

“I don’t think there’s a climate scientist alive that doesn’t think efforts to transition away from fossil fuels shouldn’t be accelerated and intensified,” he said. “The faster we transition to renewable energy sources like wind and solar, however, the less severe this problem is since the lost hydropower can be made up with noncarbon alternatives.”

This story by Kimberly M.S. Cartier was originally published by Eos Magazine and is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.