How Electoral Politics Turned Toxic

It’s not about ideas anymore. It’s about team loyalty.

|

Listen To This Story

|

– OPINION –

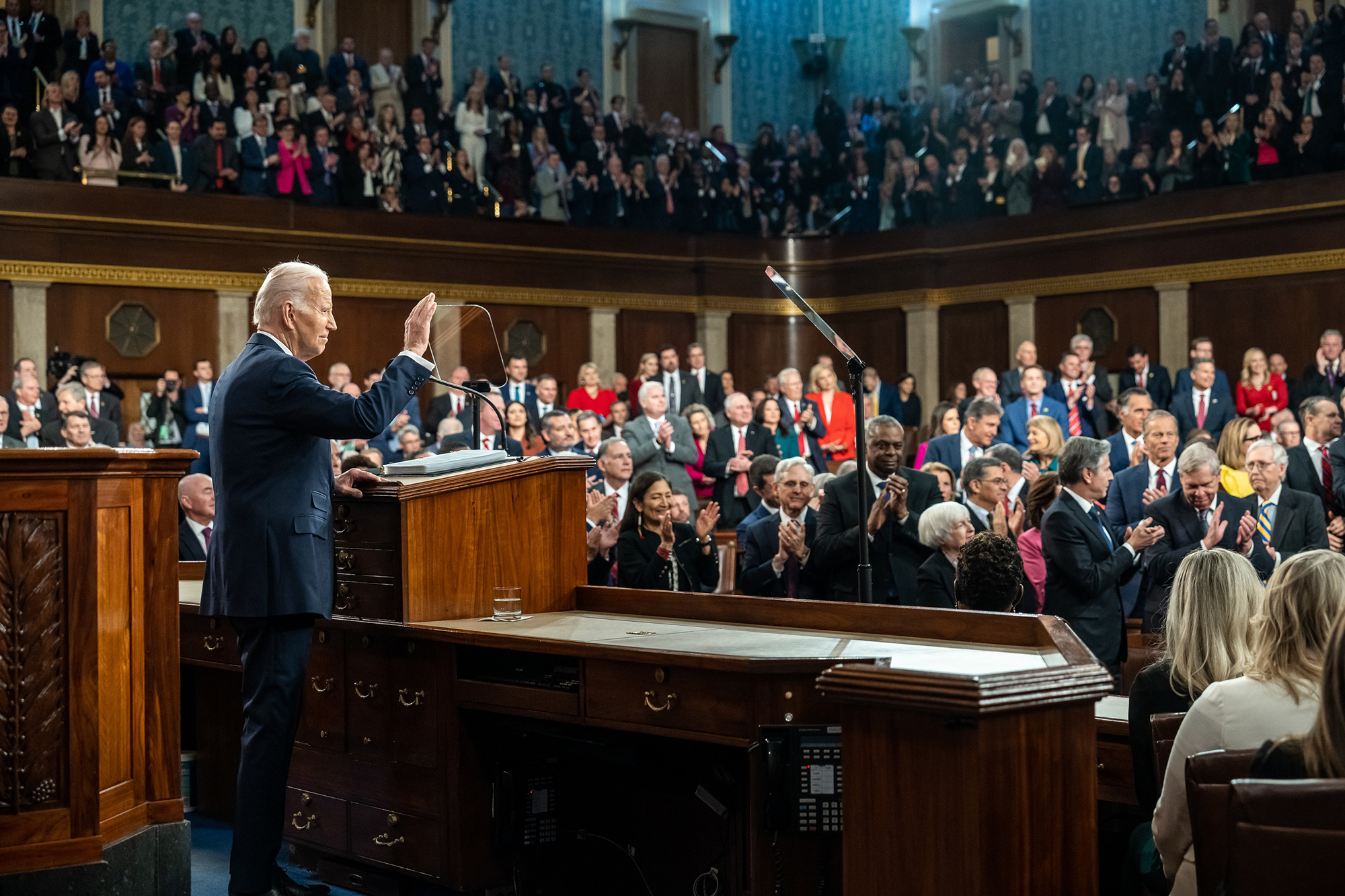

Members of Congress hollering insults at the president as he attempts to deliver his State of the Union address. The president trolling his hecklers as though he were performing at a wrestling match — which his predecessor actually did. High-ranking leaders dressed for a Hollywood red carpet rather than the people’s business. More shocking than the collapse of decorum is the fact that we are not shocked. Notable too is how we allow ourselves to be distracted from important issues by childish nonsense.

Never mind polarization; how did our politics become so viciously vacuous?

First, politics is no longer politics. The traditional basis of politics in the West, in which ideologies compete over policy, has been replaced by vapid Team Politics. Power is no longer a means to the goal of passing legislation and enacting regulations that change society, but an end in and of itself. Parties no longer promote platforms; the Republican Party didn’t even bother to have one in 2020. Democrats and Republicans promulgate their respective cultural vibes.

Party officials and politicians used to dream of securing a place in our historical pantheon, the afterlife of the republic — statues, their face on a stamp, school children forced to memorize their names and deeds. Not any more. If Ron DeSantis and Mitch McConnell and Kamala Harris are driven by a set of ideals and a vision for the future of the republic, there is little visible evidence. This generation of politicians appears to crave power as a conduit to the ephemeral, present-day pleasures of careerism and financial remuneration.

The political class is in it for themselves, not for us. And we know it. A February 5 ABC News/Washington Post poll finds that seven out of ten of Americans have little or no confidence in the president or either party in Congress to make the right decisions for the country’s future.

In one election after another, people vote for a party from which they expect nothing.

If a consumer product only came in two brands, and it was a product you could easily live without — canned pig’s feet or lava lamps — and both brands were unpalatable and unappealing, you would probably decide not to purchase either one. You’d do without. Electoral politics in the United States only offers two brands: Democrats and Republicans, neither of whom we like or trust. Voting isn’t essential to human life. Yet we talk about voting and argue about voting and, when the time comes, we vote.

We are not insane. We are acculturated from childhood by teachers and public service announcements and corporate media to believe that voting is your patriotic duty as a citizen, your most (only) effective means of expressing your opinion, and that nonvoters are indolent and apathetic wastrels. (This is not a universally held belief. Voter boycotts and casting blank ballots are respected tactics in other countries, especially in Africa.)

The other alternative, voting for a third party, is widely viewed by Americans as frivolous and silly, a wasted ballot better used for a “real” (major party) candidate who stands a chance of winning or, more often than not these days, to help prevent a victory by the other major party’s (stupid, evil, incompetent) standard-bearer. Alternative parties played big roles in the presidential elections of 1912, 1924, 1980, and 1992, but those days are over. John Anderson and Ross Perot, who may have denied Bush reelection, spooked Democrats and Republicans so badly that they began colluding in order to keep new parties from taking root and eradicate existing ones. They imposed draconian ballot-access measures, filed lawsuits against minor parties such as the Greens and Libertarians, and had their media and debate-organizer allies shadow-ban figures like Ralph Nader. Third parties have vanished from ballots in many states and have been banished from mainstream American political consciousness.

Democrats, meanwhile, threw away their attachment to liberalism in the 1990s. In their triangulating quest for moderate Republican voters, they ran away from the L-word, led by a president whose major accomplishments had been originally conceived by Republicans who couldn’t get their policies passed — because they were considered too conservative.

Over the past 30 or 40 years we have lived in a world where we feel social pressure to vote and we have only Democrats and Republicans to choose from. This zero-sum game leaves the parties two paths to try to increase their own portion of the vote. They can lure previous nonvoters to the polls, but that’s hard — only Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump have made headway among the refuseniks. More often, party strategists try to poach voters from the other party, a tactic that necessitates deviating from core ideology.

Prior to the past 30 or 40 years and going back to the great political realignment of 1932, the Democratic Party pushed liberalism while the Republican Party was the home of conservatives. As my mother explained to me, “Republicans are the party of big business and Democrats represent the common man.” There were deviations and hypocrisies — Truman turned a blind eye to McCarthy, Eisenhower criticized the military-industrial complex, LBJ dove deep into Vietnam, Nixon went to China, but — and this is as intentionally reductive as a political bumper sticker — exceptions proved the rule. Liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans mostly got what they voted for.

In search of “Reagan Democrat” swing voters, the Republican Party of the 1980s embraced full-blown apostasies that unmoored the GOP from conservative principles. Reagan ran up record deficits, betraying the party’s standard calls for smaller government. Meeting Gorbachev halfway on perestroika for nuclear-missile disarmament negotiations was a 180 degree reversal from the party’s long-standing hawkish anti-communism. Shortly after promising “no new taxes” (a GOP sop if there ever was one), George H.W. Bush signed a tax increase. Dubya- and Trump-era Republicans spent like maniacs, abandoned isolationism in favor of big new wars of choice, and even locked down the entire economy while cutting huge welfare checks to keep the country afloat. Was this your father’s Republican Party or the Soviet Union?

Democrats, meanwhile, threw away their attachment to liberalism in the 1990s. In their triangulating quest for moderate Republican voters, they ran away from the L-word, led by a president whose major accomplishments had been originally conceived by Republicans who couldn’t get their policies passed — because they were considered too conservative. Bill Clinton campaigned for and signed NAFTA, the World Trade Organization, and the anti-Black crime bill. He also gutted welfare. Hillarycare, dreamed up by the Heritage Foundation, became Obamacare and was signed into law by a president people assumed would lean left due to his race and professorial demeanor. Instead, Obama expanded the war against Iraq, unleashed a fleet of aerial assassination robots, and reacted to an economic crisis by bailing out Wall Street at the expense of Main Street. Clinton and Obama had “D”s by their names on the ballot, but their records look downright right-wing.

You could call the current era — post-Trump and possibly pre-Trump — a foreign policy realignment. Democrats have become the new war party — more hawkish on Ukraine while Republicans try to pump the brakes on war spending. The formerly belligerent GOP talked to and negotiated withdrawal with the Taliban and is willing to engage adversaries like Russia and China while right-wing Democrats push for sanctions. Republicans, formerly the party of big business, share that title with the Democrats. Our Democratic president pays occasional lip service to labor, but this White House forces striking unions back to work.

These are post-ideological party politics, policies devoid of vision save the maximization of campaign contributions. Neither party is consistent with any widely understood traditional ideological orientation like liberalism or conservatism, much less sharply defined systems like socialism or libertarianism. Their actions are ad hoc and unpredictable, a hodgepodge of whatever the algorithms indicate might best serve the latest tracking poll.

Welcome to Team Politics, in which parties do not market ideologically based policies and platform planks.

They sell tone.

Sports teams are artificial constructs whose brands center around tone. Players for the New York Mets and New York Yankees are not New Yorkers; many of them aren’t even from the United States. Yet everyone knows the Mets have more of a working-class vibe than the deep-pocketed elitists of them damn Yankees. It’s a matter of financing, location (though it’s odd that the Bronx is deemed more highfalutin than Queens), history and — most of all — effective marketing. From their color scheme to Yankee pinstripes to grandiose announcements about record contracts for new players, the Bronx Bombers are a brand everyone understands.

Democrats, formerly the party of the common man, have not so much as mentioned the need to pass an anti-poverty bill in over half a century. They have rebranded themselves as the party of coastal elites, educational attainment, effete/refined cultural tastes, the arts and NPR and strident wokery in the linguistic battles over fluctuating race, sex, and gender definitions in which progress is measured by advancing identity tokenism. Republicans, previously the preferred party of the country club, are now waging a class war Karl Marx might recognize. Under Donald Trump, who faked billionairedom before making it, the GOP became the revanchist redoubt of hillbilly high school dropouts languishing in flyover country, racist and resentful and disgruntled, white male Christians into Fox, country music, God, and big friggin’ guns.

When you vote for one party or the other, you are not choosing the future structure of Social Security or determining the decriminalization of narcotics or indicating whether or not the US will normalize ties with Iran. You are choosing which tribe to join, which table in the lunchroom is best suited for a kid like you.

The defining characteristic of tribalism is that what you are is less important than what you don’t want to be: A nerd isn’t merely bookish, a nerd is Not a Jock. Membership in a tribe is defined by exclusion, of rejection of those who don’t make the grade. We take pride in being admitted to clubs because others can’t get in: an elite college, a varsity team, a gated community, a gang. Informing people that they aren’t good enough to join your club requires at least a little contempt. Sometimes, like the Hutus and the Tutsis (an artificial distinction developed by Belgian colonizers), contempt blooms into hate.

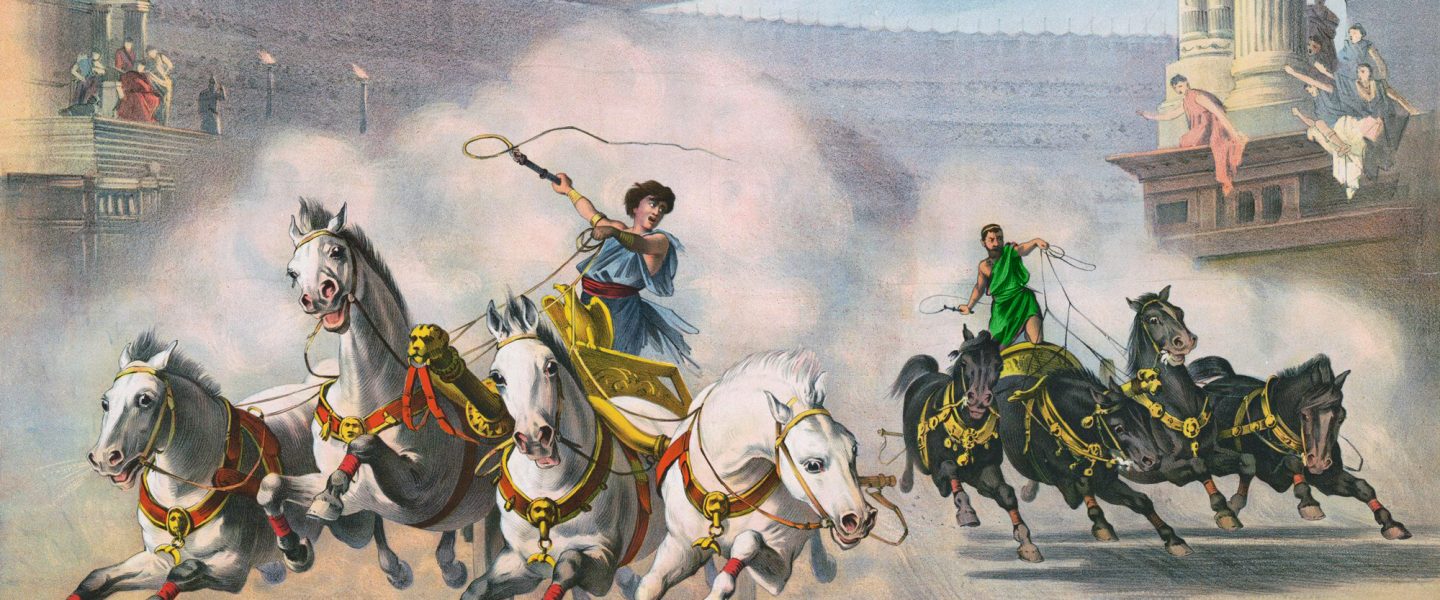

It is more than a little beautiful that our two political teams have been assigned as red and blue, colors picked by cable news channels for displays of electoral college maps. They are reminiscent of ancient Byzantium, where blind team loyalty caused chaos and bloodshed.

In the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, citizens separated themselves into fanatical devotees of the two main chariot-racing teams at the local hippodrome, the Blues and the Greens. (There had also been Reds, but they were absorbed into the Greens.) Like the Yankees and the Mets, arbitrary designations quickly assumed cultural tones: The Blues represented religious orthodoxy and the ruling class while the Greens were supported by the common people. There were Blue and Green neighborhoods and families who refused to intermarry. Riots with a political bent became common. One uprising nearly brought down the empire and led to the slaughter of 30,000 citizens, 10 percent of the population of the capital of the time.

Whether to a team or a political party, blind loyalty isn’t just stupid — as we saw on January 6, 2021, when thousands of people stormed the Capitol to avenge the “theft” of an election for which there was no evidence — it’s dangerous.

Our parents and grandparents lived in a country seesawing between liberalism and conservatism. The aforementioned apostasies of the two big political parties caused many of them to shift from one to the other from time to time, as when white Southern racists left the Democratic Party for the Republicans after LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act. Conventional wisdom divided voters roughly 45 percent for the Democrats, 45 percent for the Republicans, and 10 percent as reliable swing voters.

Under Team Politics, people vote for their favorite identity or, more precisely, their least unfavorite identity. Identity is less fluid than ideology. Liberals who may not approve of the Democrats’ foreign policy hawkishness more likely than not vote Democratic anyway, because they identify with the party’s more sophisticated rhetoric, its purported open-mindedness on LGBTQ+ issues, abortion rights, etc. Progressives, often dismissed by Democratic Party loyalists as priggish “purists,” point out that Democratic presidents like Obama and Biden murder innocent brown people in the Middle East, but their arguments fall on deaf ears because Democratic voters’ loyalty is to the Democratic Party itself, not to liberal principles.

Similarly, fiscal conservatives nevertheless continue to vote Republican despite Republican presidents’ decades-long record of out-of-control government spending. They identify with Republican optics, identifiers and signifiers about being OK with hunting and killing animals, anti-intellectualism, Christianity, not understanding transgender people, NASCAR, and nostalgia for the Confederacy and its symbols. They identify as Republicans. When they say they are conservatives, that’s a synonym for Republican. If you doubt that, quiz “conservatives” about their willingness to vote for a different party.

In a Team Politics world, there is no place to go if your party pursues policies that conflict with your principles. Democrats annoyed by what Biden is doing in Yemen will not seriously consider casting a vote for a Republican, for that would force them to identify with a loathsome underclass who want to take away a woman’s right to choose. Republicans for a balanced budget are unlikely to vote Democratic because Democrats do not support Second Amendment rights and believe transwomen are women, cultural outlooks that define them.

So the percentage of swing voters keeps dropping. Some political scientists have even declared the swing voter extinct, arguing that outcomes are determined by which party organizes the higher turnout, not the mythical people in the middle who switch parties from election to election.

In countries where electoral politics are organized around established parties, citizens share values, preferences, and ideals. Americans favor inventiveness, entrepreneurship, grit, personal freedom. We may differ about the direction the country should take, but we all like the open road, burgers, baseball.

Under Team Politics, a country replaces nationalist patriotism with tribalism. Tribal societies, like Afghanistan, do not share a strong sense of national identity. Afghans share citizenship, but their cultural and political attitudes differ by religion, sect, province, and tribe. People who live inside the same country but belong to different tribes do not feel kinship with their countrymen. Even within national borders, people otherize other tribes as much as nation-states otherize other countries. Democratic and Republican voters don’t merely disagree; they don’t dress the same or drive the same cars or listen to the same music or worship the same god or watch the same sports or drink the same beer. They are as different as the Germans are from the French.

Republicans and Democrats do not understand one another. Nor do they care to try.

Immigration is by definition a national issue. Yet the Republican governors of Texas and Florida, and their supporters, feel that they are getting rid of “their” problem when they export their migrants to “blue” states like New York and Massachusetts, an act that reflects their otherization of Democratic-majority parts of the country and their conviction that liberals don’t care about border crises because they have otherized Southern border states.

Red and blue tribesmen treat one another poorly because they mistrust each other, ascribing sinister motives. And they dislike each other intensely. An August 9 Pew Research poll found that 72 percent of Republicans believe Democrats are more immoral and dishonest. Sixty-three percent to 64 percent of Democrats say the same about Republicans. About half of Republicans (51 percent) and Democrats (52 percent) think members of the other party are more stupid. Sixty-two percent of Republicans think Democrats are lazier.

Eighty-three percent of Democrats told Pew Republicans are more closed-minded. Sixty-nine percent said the same about Democrats. On this point, both sides may be correct.

The strongest indication of blind loyalty is voluntary cognitive dissonance, the choice to believe something because fealty demands it, not only in the absence of evidence but when all the evidence indicates that that belief is false. We see it in the military, where soldiers are trained to follow orders without considering whether they make sense or the officer issuing them is competent. Religions twist the fact that there is no evidence of the existence of God into self-justification: To be blessed, the worshipful are required to take a leap of faith.

The strongest indication of blind loyalty is voluntary cognitive dissonance, the choice to believe something because fealty demands it, not only in the absence of evidence but when all the evidence indicates that that belief is false. We see it in the military, where soldiers are trained to follow orders without considering whether they make sense or the officer issuing them is competent. Religions twist the fact that there is no evidence of the existence of God into self-justification: To be blessed, the worshipful are required to take a leap of faith.

A defining feature of political tribalism is adherents’ pigheaded defense of a set of values that are internally inconsistent, like a GOP that calls itself pro-life while supporting the death penalty, and a Democratic Party that claims to be pro-choice while threatening to “cancel” people for using the wrong gender pronoun. In a healthy society, everyone agrees on the basic facts of an issue and debates what those facts mean and what, if anything, ought to be done about them.

That’s not possible under the blind loyalty that accompanies Team Politics, in which politicians can easily con people into believing things that are not and cannot be true. In the same way that fans of the New York Yankees convince themselves that a sports entertainment corporation is quintessentially reflective of their identity as New Yorkers, the Republicans who do not think climate change is caused by human activity and the Democrats who think Russia handed the 2016 election to Donald Trump have rewired their brains, bypassing logic and common sense in order to accommodate their tribal political identity.

Media silos reflect and amplify these separate realities in which American Democrats and American Republicans increasingly exist. Eighty-three percent of Fox News viewers lean Republican, receiving a steady diet of climate change denial, race-inflected crime narratives, and wokeism horror stories. The 91 percent of New York Times readers who lean Democratic are fed debunked claptrap about Russiagate while rarely raising the questions of whether an 80-year-old President Biden is up to his job or if there might be something to the Hunter Biden laptop.

How bad does this get? We already had an insurrection that was basically ignored by half — if not most — of the country. A majority of parents — 61 percent — are cool with their child marrying a member of the same sex yet would disapprove of marriage to a member of the other major political party; mixed political marriages are becoming increasingly rare. Forty-three percent of Americans told an August 31 Economist/YouGov poll they believe that there will be a civil war within the next 10 years.

There are escapes, of course. We could think our way out of the two-party trap, supporting third parties even when we are told that this election (like the previous ones) is too important to risk wasting our votes.

We could individually or collectively withhold our votes while demanding that the duopoly work harder to meet our needs. We could reject the argument that voting is a civic obligation.

We could resume identifying as liberals or conservatives or whatever, casting votes or not casting votes for political parties with whom we agree more than not, rather than reflexively voting for Democrats or Republicans because that’s just what we do.

Failing a dramatic psychological shift in the way we engage with electoral politics, we will remain a narrowly divided, highly polarized people who believe their fellow citizens who vote for the other party (or don’t vote at all) are scum.

Ted Rall is an American columnist, syndicated editorial cartoonist, and author. You can see his weekly WhoWhatWhy cartoons here. His most recent book is The Stringer, a graphic novel in which journalism meets “Breaking Bad.”