COP28: No Final Solution, But the Writing Is on the Wall

Nothing was resolved at the COP28 Conference on Climate Change except the growing conviction that the days of fossil fuels are numbered.

|

Listen To This Story

|

The COP28 international climate change extravaganza that adjourned in Dubai in December left activists hoping for an immediate transition away from fossil fuels and oil producers concerned about inevitably losing the principal source of their income in the future.

Neither side got what it wanted, but both could see the writing on the wall. Sooner or later, either fossil fuels or, in a worst-case scenario, life on the planet will face extinction. Oil producers can only hope that the end will come later rather than sooner. Conference organizers tried to slip by without mentioning that fossil fuels are on their way out, but they were eventually forced to rephrase the final resolution to declare that participating countries should at least begin moving away from using fossil fuels. Nothing definitive was said about abandoning oil and natural gas altogether, but the message to oil producers was very clear. Sooner or later, it is going to happen. The best the producers can do is to delay that final date as much as possible.

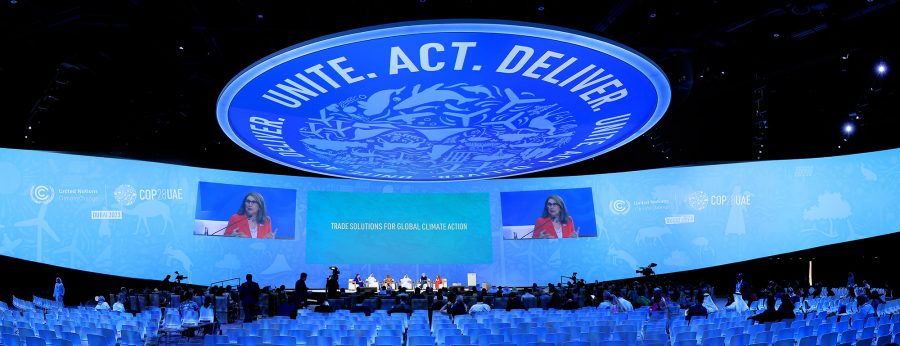

The Dubai conference, technically the 28th “Conference of Parties” to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, was enormous. An estimated 75,000 to 900,000 participants attended, along with official delegates from 198 countries and phalanxes of energy industry officials and lobbyists, environmental activists, academics, reporters and commentators, and various other hangers-on.

Dubai is the largest city in the United Arab Emirates, and its duty-free stores at the international airport are considered to be the most impressive in the Middle East. Dubai is clearly making a maximum effort to find money-making streams other than oil to secure its future, but it’s not quite there yet.

Nine days ahead of the conference, Al Jaber ignited a major kerfuffle when according to The Guardian he told former Irish President Mary Robinson, that there is “no science” linking fossil fuels and global warming.

As the hoards of participants arrived, global temperature increases were bumping close to the symbolic 1.5 C, having been measured at 1.44 C above the 20th century average for November, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Even climate-change deniers had to admit that global warming was on the march.

The United Arab Emirates is the world’s seventh largest oil producer (the US, Saudi Arabia, and Russia are Nos. 1, 2, and 3), and the 17th largest natural gas producer (the US, Russia, and Iran are Nos. 1, 2, and 3).

The chairman of the COP28 meeting was the UAE’s 49-year-old technology minister, Sultan al-Jaber, who is head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. (ADNOC), the UAE’s state-owned oil company. Al-Jaber is also the founder of Masdar, a renewable energy company with a respectable global reach.

Nine days ahead of the conference, al-Jaber set off a major kerfuffle when, according to The Guardian, he told former Irish President Mary Robinson that there is “no science” linking fossil fuels and global warming. Al-Jaber allegedly added that phasing out oil, gas, and coal would push humanity “back to the caves.” Predictably, al-Jaber later claimed that he had been misunderstood.

The interests backing fossil fuels nevertheless played a major role at the conference. One activist group estimated that there were some 2,400 oil industry lobbyists at the conference. That may be hyperbolic. There is no question, however, that there were plenty. The Associated Press reported that “at least 15 people” in the official Saudi Arabia delegation “appear to be undeclared employees of the Saudi state oil company, according to research by an environmental nonprofit.”

The COP28 results highlight three major topics:

- Fossil Fuel Phase Out. A push to banish coal, oil, and gas generated the most heat. Nongovernmental climate activists and countries lacking in major fossil fuel infrastructure called for the exiling of the major sources of heat-trapping carbon dioxide produced from burning coal, oil, and gas. The US supported a phase out. Natural gas is a double-dipping greenhouse gas. Burning gas produces CO2. Its chief component, methane, is a greenhouse gas itself, more potent that carbon dioxide but less long lasting.

The policy tug-of-war lasted until the final hours of the conference. As departures dawned, the weary delegates agreed to language providing for what they call the “global stocktake”: “Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science,” adding, “Phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions, as soon as possible.” Specific targets for coal, oil, and natural gas were not addressed, but methane got a specific mention, a holdover from COP27. The agreement deliberately avoids calling for a “phase out” of fossil fuels, only a phase out of subsidies.

Echoing a UN press release, The New York Times headlined its main story on COP28, “In a First, Nations at Climate Summit Agree to Move Away From Fossil Fuels.” Not exactly a first. At last-year’s COP27, held in Egypt’s Red Sea resort town Sharm el-Sheikh — notable mostly for how Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s secret police rounded up, beat up, and jailed demonstrators — the conference adopted language calling for “rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures, including accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.”

- Loss and Damage. The developed world has grown and thrived over the past 200 years on an industrial foundation built on coal, oil, and gas. The largely agricultural poor world, a majority of the world’s nations, bear the strange fruit of that imbalance, global warming that threatens them directly. At the same time, many of these countries have large, untapped fossil fuel reserves. The world is now telling these countries they must eschew their underground wealth.

At Dubai, Ruth Nankabirwa Ssentamu, Ugandan minister of energy and mineral development, told rich countries to “go first” on phasing out fossil fuels. She said, “To tell us to stop fossil fuels is an insult. It’s like you are telling Uganda to stay in poverty. We could accept a long-term phase out, if it made clear that developing nations can exploit their resources in the near term, while wealthy long-time producers quit first.”

The UN already recognized the critical disconnect described by Ssentamu at COP15 in 2009. The solution proposed then was to funnel dollars to the less-developed world, compensating them for the losses and damages caused by the developed world’s exploitation of greenhouse gasses. While the word “reparations” is taboo when it comes to climate talks, that’s what it’s about. But no dollars have ever changed hands. COP27 called for a fund but offered no details.

The first step the Dubai delegates took was to again address loss and damage. A UN press release said, “Delegates meeting in Dubai agreed Thursday on the operationalization of a fund that would help compensate vulnerable countries coping with loss and damage caused by climate change, a major breakthrough on the first day of this year’s UN climate conference.” The formal language called on the World Bank to found and manage the fund.

The UAE said it would commit $100 million to the fund, as did Germany. The US said it would pitch in, without specifying an amount. Most analyses predict that billions will be needed.

Shannon Gibson, associate professor of international relations and environmental studies, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, says much is “missing” from the fund.

Gibson writes that the language “contains no specifics on scale, financial targets or how it will be funded. Instead, the decision merely ‘invites’ developed nations to ‘take the lead’ in providing finance and support and encourages commitments from other parties. It also fails to detail which countries will be eligible to receive funding and vaguely states it would be for ‘economic and non-economic loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events.’ So far, pledges have been underwhelming.”

- Nuclear Power. Nuclear power seems an ideal companion to a decline in fossil fuels to generate electricity. Nuclear plants emit no greenhouse gasses, can run continuously, and generate large amounts of electricity. Yet nuclear power has been lagging since the boom years of the 1970s, in large part because of economics. Plants are capital-intensive, incur large construction debt loads, and take a long time to build.

The COP28 recommendations include a plea for a tripling of low-emission, electricity-generating technologies such as the major renewables: wind and solar power. The nuclear section on the global stocktaking barely mentioned nuclear in passing, the first time the atom got COP billing. The conference made no call to triple nuclear power.

Nuclear energy interests intentionally trumpeted this as a call for a tripling of nuclear power sources. Maria Korsnick, CEO of the Nuclear Energy Institute, the US nuclear power trade association, said, “As I meet with world climate leaders this week in Dubai for COP28, I am heartened to see this momentum clearly reflected in the dialogue taking place. Today, government leaders from around the world called for a tripling of nuclear capacity by 2050 because it is critical for meeting our global climate goals — an imperative echoed by my fellow industry leaders.”

Rafael Mariano Grossi, director general of the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency said, “Nuclear energy’s inclusion in the Global Stocktake is nothing short of a historic milestone and a reflection of how much perspectives have changed.”

The US Department of Energy misleadingly titled an article, “At COP28, Countries Launch Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy Capacity by 2050, Recognizing the Key Role of Nuclear Energy in Reaching Net Zero.”

The IAEA press release let the radioactive cat out of the bag, noting that “the inclusion of nuclear, together with a separate declaration made last week at COP28 by more than 22 countries to advance the aspirational goal of tripling nuclear power capacity by 2050, as well as statements by the IAEA and the nuclear industry, underscored the momentum building behind the world’s second largest source of clean electricity.”

The New York Times reported, ”The United States and 21 other countries pledged on Saturday at the United Nations climate summit in Dubai to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050.” It wasn’t a COP28 recommendation endorsed by 198 nations.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists panned the plan, calling it a “numbers racket.” Sharon Squassoni, research professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, wrote, “It seems like an impressive and urgent call to arms. On closer inspection, however, the numbers don’t work out. Even at best, a shift to invest more heavily in nuclear energy over the next two decades could actually worsen the climate crisis, as cheaper, quicker alternatives are ignored for more expensive, slow-to-deploy nuclear options.”

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists panned the plan, calling it a “numbers racket.” Sharon Squassoni, research professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs, wrote, “It seems like an impressive and urgent call to arms. On closer inspection, however, the numbers don’t work out. Even at best, a shift to invest more heavily in nuclear energy over the next two decades could actually worsen the climate crisis, as cheaper, quicker alternatives are ignored for more expensive, slow-to-deploy nuclear options.”

COPs are aspirational. They offer a wish list, not a road map. They also provide a rough scorecard: dollars distributed; windmills and solar panels installed; and, most important, the scope and direction of global temperatures.

So far, the climate is losing. CNN noted, “U.S. oil production is at a record; India plans to double coal output by 2030; the UK is issuing new drilling licenses in the North Sea; and American oil majors are splurging billions on deals that signal they see robust demand for decades to come.”

The Washington Post editorialized, “Countries are not on track to hit the global climate targets they set in previous summits; these targets are not enough to prevent warming in excess of 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial averages, the ostensible goal; everybody will propose new targets in a couple of years. Yet the conference’s conclusions on how to make progress from here are so vague that the countries’ promise seems empty.”

The annual UN conference started in Berlin in 1995, an event that generated a minor story on page A6 in The New York Times, headlined “Disputes Dim Prospects for Limits on Carbon Dioxide Emissions.”

COP3 in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997 saw US Vice President Al Gore pushing the meeting to adopt what came to be known as the “Kyoto Protocol,” a “legally binding” commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 6–8 percent annually from 2008–2012, based on a 1980 base level and starting in 2005. It was, of course, not actually legally binding. Global greenhouse gas emissions, led by carbon dioxide, increased by 32 percent from 1990 to 2010, according to the UN’s Environment Programme.

COP21 in Paris in 2015, made the biggest splash. The delegates agreed to the “Paris Agreement,” setting targets to limit the global temperature preferably to 1.5 C (2.7 F) or at most 2 C (3.6 F) above “pre-industrial levels.” Record keeping began in 1880.

Legendary songwriter Willie Nelson in 1967 wrote lyrics that are a fitting farewell to COP28: “Turn out the lights, the party’s over. They say that all good things must end. Call it a night, the party’s over. And tomorrow starts the same old thing again.”