Stories of betrayal upon betrayal.

|

Listen To This Story

|

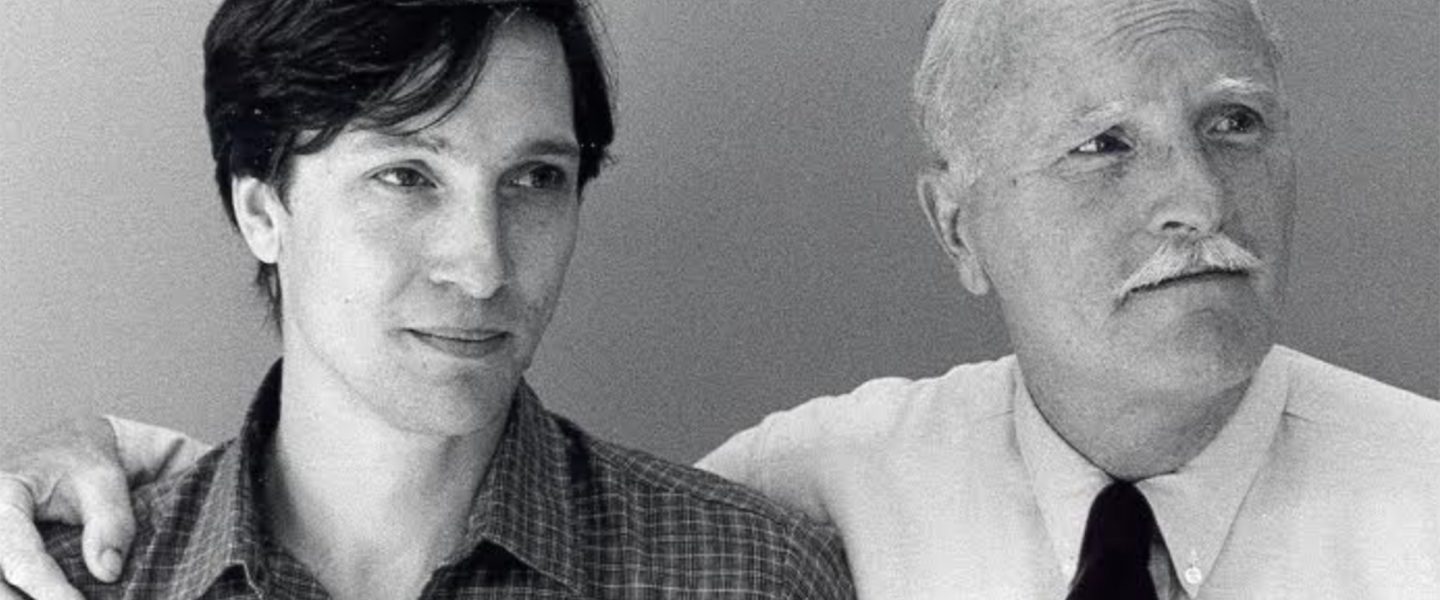

In the following story, Nicholas Schou –– author of Spooked: How the CIA Manipulates the Media and Hoodwinks Hollywood, and Kill the Messenger: How the CIA’s Crack Cocaine Controversy Destroyed Journalist Gary Webb — interviews Douglas Valentine about his new book, Pisces Moon: The Dark Arts of Empire, published in May of this year by Trine Day.

As the publisher put it, this book “tells how the American empire was created by rapacious businessmen backed by a murderous military establishment, media moguls who designed a relentless psychological warfare campaign that glorifies warriors who are programmed to kill on command.”

It’s also a very compelling personal story, told in the first person.

The introduction below is Schou’s, followed by the interview. His questions appear in bold.

***

In the early 1990s, when the US began to normalize relations with Vietnam, Douglas Valentine, then a young author and historian of US foreign policy based in New England, saw an opportunity to travel to Southeast Asia on a mission to uncover some of the lingering secrets about the American presence in the region.

Valentine, the son of a haunted veteran of World War II, had just published a definitive yet controversial history of the CIA’s Phoenix program in Vietnam (The Phoenix Program: America’s Use of Terror in Vietnam). He hoped to meet with former CIA spooks, still living there, who had participated in some of the darker aspects of our military and political activities during the war.

Although Valentine has since written several important books on the CIA and other US government agencies involved in Vietnam and Washington’s war on drugs, it took him three decades to publish a full account of his travels to Southeast Asia. Shortly after the publication of this new book, Pisces Moon: The Dark Arts of Empire, Valentine discussed his life and career as well as some of the highlights of his efforts to get often distrustful and downright jittery subjects to divulge their secrets.

***

Nicholas Schou: To a certain extent, your entire career as an investigative writer is based on inside access, starting with The Hotel Tacloban, your book about the POW camp where your father was held by the Japanese. For people who don’t know about your father’s experience in World War II, can you explain what happened to him in New Guinea and the Philippines and how that affected him and your relationship with him?

Douglas Valentine: I had a strained relationship with my father for the first 30 years of my life. My father was a mystery to me. He held a grudge against the US army. We disagreed on just about everything, including Vietnam, and when it came time for me to head off to college, I couldn’t get away from home fast enough. Our final break occurred after I dropped out of school in my senior year. We hadn’t spoken for eight years when he called shortly after his second open-heart [surgery]. “You’ve always wanted to be a writer,” he said. “Come home. I have a story to tell you.”

And that’s how my writing career began. So he told me about his WWII combat experience in New Guinea and about his capture and internment in a Japanese POW camp in the Philippines. All of which he’d kept secret under threat from the military authorities. There’d been a mutiny in the camp and my father was made to sign a nondisclosure statement and vow never to tell — on pain of being tried and executed for treason.

The military denied the POW camp ever existed. And in the process of telling me his story, he accepted full responsibility for laying his burden on our family. He transcended his machismo and sexism and racism, and we became best friends. And not only did I learn how to write, I learned the facts about war and government secrecy and a lot of other things that made it possible for me to connect with CIA officers. I learned how to talk with hard men and interpret their subliminal messages.

NS: Without Hotel Tacloban, you never would have been able to get the kind of access that allowed you to write your book on Operation Phoenix. What made you interested in exploring the darkest annals of the Vietnam War and what was it like meeting William Colby and the various other spooks you interviewed?

DV: I got onto Phoenix by chance. I felt there were three issues that most deeply affected my generation: civil rights (race and sex), drugs, and Vietnam. I felt that researching and writing about them was the key to my understanding of America. I also wanted to do something original and close to my heart, so I went to a local VA hospital and asked the director if there were any secret operations during Vietnam that hadn’t been written about. Right away he said Phoenix.

After explaining a little about it, he mentioned that one of his clients had been in Phoenix and that his client’s service records, like my father’s, had been “sheep-dipped” — altered. The records showed that he had been a cook in Vietnam. But when I asked to interview the client, the fellow refused. Formerly with Special Forces in Vietnam, he was disabled and afraid the Veterans Administration would cut off his benefits if he talked to me.

That fear of the military, so incongruous on the part of a war veteran, made me more determined than ever to uncover the truth about Phoenix. I approached it in two ways. I wrote directly to William Colby, who’d been a director of the CIA and was the CIA officer most closely associated with the program. Colby had testified at public hearings about Phoenix in 1970, ’71, and ’73. And I started approaching Vietnam vets.

I worked from both ends toward the middle, getting both the stated policy and the operational realities.

I don’t know why Colby agreed to meet me. I was a nobody. I’d written a book about my father’s wartime experiences, which showed I understood and empathized with foot soldiers, but I wasn’t Gloria Emerson or any of the other famous Vietnam War correspondents who had actually had CIA officers as sources. But Colby agreed to help and started referring me to high-ranking CIA officers who had participated in the program and its component parts. Anti-war veterans were glad to help, too.

It’s impossible to describe in this format what interviewing them was like. Read Pisces Moon for that. In any event, Colby liked my liberal arts and organizational approach. He liked The Hotel Tacloban. He knew I’d understand the complexities, plus, I guess, I was untainted. He started introducing me to a lot of senior CIA people. Some saw in me their son. Many thought I was a CIA officer because, well, Colby had sent me. That gave me access from the inside. After that it was pretty easy. I was able to persuade a lot of these CIA people to talk about Phoenix and the CIA in general.

NS: The reaction to your book was fierce, but how much of a surprise was that to you? What was it like to experience this backlash? Morley Safer’s [1990] review failed to find any fault whatsoever in the facts you presented, yet he still saw fit to savage your writing. Why do you think he felt compelled to attack you, and how did all this affect your writing career and prospects as an author?

DV: You can’t do this kind of work and be intimidated. And I fully expected to get pilloried or ignored and never write another book again. But in 1989 my editor at Willliam Morrow said he would nominate the book for a Pulitzer Prize, and John Prados, the historian he had asked to review the book, said it was the missing piece in Vietnam War history. After the BBC hired me in the spring of 1990, I started thinking, well maybe I’m not cooked.

Then came the public humiliation of Safer’s half-page review in The New York Times. I was annihilated. I lost all confidence. I remember asking author and former Vietnam War correspondent Nick Proffitt, who had written a nice blurb, whether I was a real writer. He said it was a great book and well written. The review was just a hit job.

It was how the CIA, military, and Vietnam War correspondents got their revenge on me. So I brushed myself off and vowed renewed vengeance on all of them by exposing their involvement in the drug trade. I became determined to write another book, even though Peter Dale Scott told me I’d never get another book published in the US again.

In 1993, I forced the CIA in federal court to reveal the file it had been keeping on me since 1986. An astrologer said I could work my way back writing articles, and soon thereafter Alex Cockburn and Jeff St. Clair at CounterPunch took me under their wing.

Cockburn rated Phoenix one of 100 best nonfiction books of the 20th century and he kindly got my first drug book, The Strength of the Wolf, published at Verso. A few years later John Prados placed all my Phoenix and drug war book research material at the National Security Archive.

Which brings me to the end of the Safer saga. About 10 years ago, I finally found out why Safer had been selected to destroy my career. I thought Safer hated me for accusing the press corps of covering up the CIA’s war crimes. I thought he did it for pecuniary reasons too; his self-congratulatory book on Vietnam had come out a few months before mine.

Then, through a friend in Europe, I found out that Safer owed William Colby a favor. Safer revealed this incestuous relationship with Colby for the first time at the American Experience conference in 2010. (Colby had apparently expected me to write an official version of the Phoenix program.)

NS: You subsequently wrote two books on the US drug war, both of which probed the extent to which formal US drug policy was consistently and purposefully undermined by foreign policy considerations which have never been officially acknowledged. What is the most important lesson you learned in this research that the public needs to understand?

DV: There are two lessons. The first is that “honest” federal drug agents (who broke all the rules to make cases), in the course of their work, discovered that the military-political-industrial establishment was intimately connected to the criminal underworld and that, after World War II, the CIA ran the international drug trade on this establishment’s behalf.

That situation existed until 1968, when the old Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) was reorganized within the Justice Department and the CIA — in order to protect the drug-trafficking generals and politicians who were fighting, on America’s behalf, the wars against national liberation in Southeast Asia — infiltrated and commandeered the executive management, intelligence, and special operations branches of the new federal drug enforcement agency, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD).

With the creation of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973, federal drug law enforcement became an adjunct of the security state. With the creation of the Department of Homeland Security in 2002, and the militarization of state and local law enforcement — plus the proliferation of heavily armed right-wing militias under their control — the US government became the largest organized crime gang in the world, on behalf of the war industry establishment and protected by the security state. Which, as I explained, includes the media.

The second lesson is that this situation will never change. We’re locked in. Which is why it’s now a spiritual, not a political, matter. Everyone is on their own.

NS: Besides Operation Phoenix, the CIA’s involvement with Southeast Asian drug trafficking during the Vietnam war remains the agency’s darkest secret from that era. How did you get on the trail of this story, and what were you hoping to uncover about it on your trip to Vietnam and Thailand?

DV: I started learning about the CIA’s involvement in Southeast Asian drug trafficking while researching Phoenix. It was a hot topic. Iran-Contra was in full swing and I started reading about that. I read Al McCoy’s The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia as much to learn about the South Vietnamese police and security services as to learn about the drug trade. McCoy talked a lot about Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan who, after 1965, ran the intelligence, military, and national police services in South Vietnam. Loan put together a political machine for his boss, Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky, and reorganized the opium traffic out of Laos as a means of financing counterinsurgency operations. And by chance, I met Loan’s CIA adviser, Tullius Acampora, early in my Phoenix research. Not even McCoy had that access.

The FBN is the main subject of my first drug book, The Strength of the Wolf. The FBN existed from 1930 until 1968. Andy Tartaglino and Fred Dick became agents in the early 1950s and through them I learned everything and met everyone of any significance, including “the corrupt” case-making agents who made the Mafia and the French Connection. One thing led to another, and with very few exceptions, the agents I located were agreeable and eagerly discussed everything that contributed to the FBN’s successes and failures. It didn’t take long to realize that I had a chance to do something truly original: that these FBN agents were a new cast of characters on America’s historical stage, and that their collective recollections were a priceless contribution to American history.

Most importantly, they hated the CIA — those who weren’t actually in its employ. I wrote the sequel to Wolf, The Strength of the Pack, about the CIA’s infiltration and commandeering of the BNDD and DEA. By then, the CIA was following me everywhere I went.

One last story about that. In 1994 I had arranged to interview the acting DEA administrator, Steve Greene, at his office at [the] DEA HQ. His public relations officer, Bill Ruzzamenti, met me downstairs and personally brought me up the executive suite. He got me coffee and put the Safer review in front of me. I scoffed. Then he said, “The CIA called. They told us not to talk to you. They said you’re trying to get at them through us.”

“I’m investigating international drug trafficking and doing a book on the BNDD and DEA,” I said. “But if I find out the CIA was impeding federal drug law enforcement in any way, I’m going to write about it.”

Ruzzamenti smiled a big smile and said, “That’s exactly what we wanted to hear.” Then he led me into Greene’s office.

Like I said, the old narcotic agents (those who weren’t actually in it undercover) hated the CIA. But all that has changed. Everyone in government works for or through the military and security services now.

NS: Of all the spooks you met with, who was the spookiest? Did Tony Poshepny live up to his gruesome reputation or were there even creepier contacts you made?

DS: Tony Poshepny was definitely spooky and gruesome. Apart from serving in Thailand and Laos for many years, he’d been on secret missions into Indonesia, Tibet, the Philippines, and Cambodia. Probably into China and North Vietnam too. And he was still operating when I met him.

He told me that the huge Chuck Norris-Rambo political-media campaign to publicize the search for American MIAs and POWs in Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia after the war was a psychological warfare operation that provided a cover for CIA efforts to track and try to assassinate 55 US deserters who had escaped from military prisons, mostly Negroes and Hispanics guilty of fraggings, and had gone into tunnels and onto farms with the Viet Cong. My own experience in Vietnam confirmed that. It’s in the book.

Essentially, Poshepny was [a] paramilitary case officer who was based so far “up the river” in Laos that no one knew he was there. His claim to fame was as a ruthless jungle fighter. Poshepny was at it longer than most, but plenty of CIA paramilitary officers and Army Special Forces and Navy SEALs did the same stuff. Some even feasted on human body parts as part of the CIA’s legendary bag of psywar tricks to terrorize people into submission. But the typical B-52 crew killed and mutilated far more people in a month than those guys killed and maimed in their lifetimes. As did guys like Richard Secord, who managed the bombing campaigns from behind a desk, for mass murderers like Henry Kissinger.

NS: Tell us about the journey to get this book published. Why did it take so long, and do you feel like now that you’ve published it, your work is done? Reading Pisces Moon, one gets the sense that we still only know a fraction of the terrible truths that exist beyond our knowledge? Are you done trying to uncover secrets? And either way, what do you think might be the biggest secret that is still out there?

DV: There’s an ancient myth that Greek sailors journeyed to a distant world in the West every 28–30 years upon the completion of Saturn’s voyage around the sun. Likewise, Pisces Moon notes sat in the drawer for 30 years waiting for the stars to realign. I say that half-jokingly. But I could not have written a memoir 30 years ago. I had to enter the final phase of my life and acquire enough understanding of me and America to tell the story, with its fated ending.

In other words, I needed Trump to emerge from his cesspool of xenophobia, racism, sexism, greed, and megalomania. Recognizable as the media spectacle’s darkest creation, a high-tech Frankenstein’s monster, Trump was also recognized as the incarnation of what Bill Burroughs called the “backlash and bad karma of empire.” At first, I stood in awe as he “sucked all the air out rationality,” as Seymour Hersh put it to me. But it was obvious, after his 2016 campaign when he said Hillary Clinton could win only by fraud, that he would not go peacefully if he lost the 2020 election.

By 2019, with the proliferation of his private army of right-wing militias, I started to sketch Pisces Moon. After he botched the pandemic and the George Floyd protests, I put everything else aside and got down to it. And once I started, it was an easy book to write.

For 75 years, the CIA has been buying strongmen, legislators, and judges, equipping them with thugs, and then wrapping the whole package up in Big Lies, to conduct coups, autocoups, and countercoups. It was our fate as a nation that Trump would magically appear to subvert and conquer America by using all the dark arts the CIA has perfected to subvert and conquer much of the world.

All the mythological energy was there; I just had to harness it. Pisces Moon is a book about America and where I fit in it, but no serious leftist publisher would ever publish a book that employs astrology, even as a literary device. I would have self-published Pisces Moon, but Kris Millegan at TrineDay saw its worth and here it is. And with it, I’m done.

I’m sure there are terrible state secrets yet to be discovered, historical and current. But the security services have closed all the loopholes since 9/11, when the Phoenix program was imported to America as the Department of Homeland Security. No one will ever crack the remaining big secrets.

The horse and buggy days of tracking down people with inside stories is a thing of the past. With Trump, we’ve reached the end of knowing. In its place we have Glen Greenwald and a throng of internet experts rattling around in the spectacular dream world, claiming they’re in on the secret. That’s it. Which doesn’t mean you can’t do good deeds and create art.

If I had it in me, I’d write a novel about a revolutionary man and a counterrevolutionary woman falling in love. Can love triumph? That’s the overwhelming question. How to make the personal the political… to keep the mind open to the synchronistic link to the cosmos. To feel responsible for the planet and everyone on it. What else can anyone do?