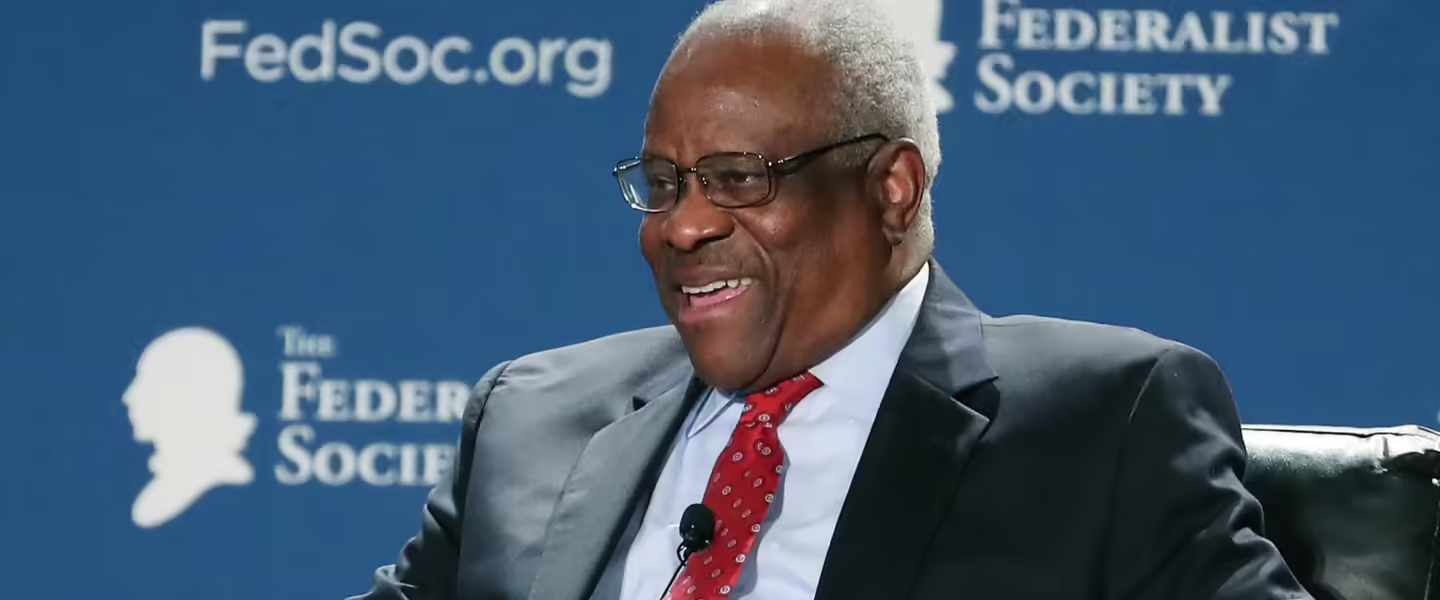

Glory Be! Justice Thomas Takes One for the Team!

Clarence couldn’t just stand by and watch the Court gut the Second Amendment!

|

Listen To This Story

|

Well, I guess somebody has to stand up for the rights of spousal killers, wife beaters, child abusers, and the Second Amendment, and I’ll just bet you can guess who it is.

This past Friday, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas stepped up and took one for the team, voting alone against the 8-1 decision in United States v. Rahimi that bars people from possessing firearms while they are under domestic violence restraining orders. Not stripping them of the right to own guns, mind you, but only suspending that right under the Second Amendment until such an asshole can get the restraining order straightened out so he can get his guns back.

Thomas must be spending so much time in the history stacks in the Fairfax County Library, where he lives in Virginia, that they’re probably considering buying a cot for him to take naps on during his long hours of study of our laws in the 1700s and 1800s, not to mention old English law and a few ancient Greek statutes he quoted in his 2022 Bruen gun rights decision.

Perusing the laws that were in existence at the time of our nation’s founding, Thomas wrote in his dissent in today’s case that “Not a single historical regulation justifies the statute at issue.” The “statute at issue” suspends the right of those under domestic violence restraining orders from possessing guns.

Chief Justice John Roberts appears to be the one who convinced four of the other six gun nuts on the court, all of whom voted to allow bump stock-equipped machine guns earlier in the week, to join him in at least temporarily coming to their senses.

Roberts was able to somehow resurrect enough common sense on the court that he got enough votes to rule, as the author of the decision, that “an individual found by a court to pose a credible threat to the physical safety of another may be temporarily disarmed consistent with the Second Amendment.” I mean, whoop-de-fucking-doo, but I guess we are in the position of taking them when we can get them, right?

“Some courts have misunderstood the methodology of our recent Second Amendment cases. These precedents were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber,” Roberts wrote. “The Second Amendment permits more than just those regulations identical to ones that could be found in 1791.”

The plaintiff in the case, one Zackey Rahimi, is a convicted drug dealer who had beaten his girlfriend to the ground in a parking lot and was dragging her back to his car when a bystander intervened. Rahimi fired a shot at the bystander, and the girlfriend took that opportunity to escape. Rahimi called her later and threatened violence — specifically, he said he would “shoot” her — if she told anyone about the incident. The girlfriend asked a Texas court to issue a restraining order and amazingly they agreed, finding that Rahimi had committed “family violence,” and suspended his right to possess guns while the restraining order was in effect.

Rahimi managed to hang onto enough firearms that he was involved in five shootings in the following months, according to the Supreme Court brief filed by the Biden Department of Justice. Rahimi was charged with illegal possession of a firearm, convicted in federal court, and sentenced to six years in prison.

But Rahimi continued to argue that his rights under the Second Amendment had been violated. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Rahimi at his first hearing, but after Justice Thomas wrote the decision in Bruen, ruling that laws restricting firearms had to be rooted in the “history and tradition” of this country, the Fifth Circuit reheard the case and, incredibly, ruled for Rahimi.

Citing the Bruen case, a Trump appointee on the court wrote that while the federal law banning people under restraining orders from possessing firearms was “meant to protect vulnerable people in our society … our ancestors would never have accepted” laws against domestic violence.

The decision by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals was unanimous, so Rahimi’s right to keep and bear arms under the Second Amendment was restored.

The case was appealed by the DOJ to the Supreme Court, where many legal experts feared it would hit the “history and tradition” brick wall of Thomas’s Bruen decision. Chief Justice Roberts, however, appeared to back the court away from that decision a bit today. “Some courts have misunderstood the methodology of our recent Second Amendment cases. These precedents were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber,” Roberts wrote. “The Second Amendment permits more than just those regulations identical to ones that could be found in 1791.”

Roberts cautioned that if courts hearing gun cases were to consider only laws in existence at the founding of the country, they would find laws dealing with “muskets and sabers.” Instead, Roberts urged courts that will interpret his decision in the future to consider whether a gun regulation at issue is “relatively similar” to regulations that were in effect closer to the nation’s founding. “For example,” Roberts wrote, “if laws at the founding regulated firearm use to address particular problems, that will be a strong indicator that contemporary laws imposing similar restrictions for similar reasons fall within a permissible category of regulations.”

In the amazingly dull and nearly impenetrable language of the Supreme Court, that comes as close as we will ever get to a relaxation of the Thomas decision in Bruen, which courts like the Fifth Circuit have interpreted as turning back the clock to the way guns were regulated in 1791, which is to say not at all.

That may be why Thomas was the lone dissenter in the decision today, because it took some of the edges off his celebration of guns-for-everybody in the Bruen decision. Or maybe Thomas, in his history-stacks-diving on domestic violence laws, discovered, as he has before, a favorite old English construction of what husbands and domestic partners are permitted to do to the women in their lives: the “rule of thumb.”

It’s not like this subject hasn’t been dealt with before. In January of 1982, the US Commission on Civil Rights issued a report that was entitled “Under the Rule of Thumb: Battered Women and the Administration of Justice.” The Commission found that when it came to domestic violence, “American law is built on the British Common Law that condoned wife beating and even prescribed the weapon to be used. This ‘rule of thumb’ stipulated that a man could only beat his wife with ‘a rod not thicker than his thumb.’”

The Commission noted that William Blackstone, who “greatly influenced the making of law in the American colonies,” commented thusly on the rule of thumb: “For as the husband is to answer for her misbehavior, the law thought it reasonable to entrust him with this power of chastisement, in the same moderation that a man is allow to correct his apprentices or children.”

American courts, bless their bleeding hearts, can be said to have taken up the rod passed to them by the Brits. Have a look at this from an 1864 court in a case of a man who choked his wife:

The law permits him to use towards his wife such a degree of force, as is necessary to control an unruly temper, and make her behave herself; and unless some permanent injury be inflicted, or there be an excess of violence, or such a degree of cruelty as shows that it is inflicted to gratify his own bad passions, the law will not invade the domestic forum, or go behind the curtain. It prefers to leave the parties to themselves.

The Civil Rights Commission quoted a Mississippi Supreme Court case from 1824:

Let the husband be permitted to exercise the right of moderate chastisement, in cases of great emergency, and use salutary restraints in every case of misbehaviour, without being subjected to vexatious prosecutions, resulting in the mutual discredit and shame of all parties concerned.

After an Alabama court had rescinded the right of a man to beat his wife in 1871, a North Carolina court came along and provided some relief to all those poor men who had to deal with those damn recalcitrant women:

If no permanent injury has been inflicted, nor malice, cruelty nor dangerous violence shown by the husband, it is better to draw the curtain, shut out the public gaze, and leave the parties to forget and forgive.

Thomas, in his dissent that would allow abusive husbands and male partners under court restraining orders to own guns, would appear to smile upon Ye Old Rule of Thumb as well. It’s history and tradition, you understand — Thomas’s favorite harkening back to the good old days when a man was allowed to own not only a gun, but a stick big enough to beat his wife with.

Reprinted, with permission, from the Lucian Truscott Newsletter. Lucian K. Truscott IV has had a career spanning five decades as a journalist, novelist, and screenwriter.