Does Netanyahu Really Qualify as a Criminal? It’s Complicated

Israel’s attack in Gaza has killed more than 36,000 Palestinians in response to Hamas killing 1,250 Israelis on October 7. Can self-defense turn into a war crime?

|

Listen To This Story

|

Israel’s embattled prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, clearly has a growing problem with the law. First, he attempted to neutralize Israel’s Supreme Court, which was getting in the way of his efforts to continue his 20-year grip on political power. Now his seven-month onslaught in Gaza has earned him a possible arrest warrant from the International Court of Criminal Justice (ICC).

In case he did not get the ICC’s message, the World Court ordered Israel to immediately halt its operations in Gaza. In spite of the World Court’s decree, Israel’s national security adviser, Tzachi Hanegbi, predicts that the fighting in Gaza is likely to last for another six or seven months. In practical terms, it’s hard to see how any of the court rulings can be enforced. Nevertheless, the cumulative impact does not bode well for Netanyahu — or for Israel.

Both the World Court and the International Criminal Court are initiatives of the United Nations and have their headquarters at The Hague in the Netherlands. The World Court was created along with the United Nations in the immediate aftermath of World War II. The International Criminal Court came along later. It is based on a treaty called the Statute of Rome that was signed by 60 countries in 1998. It began official operations in 2002, and currently at least 124 countries agree to its jurisdiction.

While the World Court, also known as the International Court of Justice, deals with disputes among nations, the International Criminal Court (ICC) deals with specific individuals charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

When World War II ended much of the world was still claimed by the former colonial powers, mainly Britain and France in Africa and India, Belgium in the Congo, and the Netherlands in Indonesia. Although Russia quickly extended its control over Eastern Europe, instituting what Churchill referred to as the “Iron Curtain,” post-war sentiment in Western Europe was generally opposed to continuing colonial exploitation. Everyone was exhausted, and since many of the colonial territories had recruited local partisans to fight the Axis powers, these forces became engaged in their own fight for independence.

Ho Chi Minh was a case in point. After the Vietnamese resistance leader helped rescue a downed American pilot, the US government’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS) recruited him as an agent, code-name “Lucius,” to fight the Japanese occupation in Vietnam. After World War II ended and the French became engaged in a desperate struggle to prevent Ho from taking control in Indo-China, US military aid to France was handled by the European desk at the US State Department, since the US still considered Vietnam to be a French possession.

While the transition from colonialism to Third World independence was obviously desirable, the abrupt fashion in which it was carried out left most of these former colonies exposed to a chaotic competition among unscrupulous opportunists bent on profiting from as much of the Third World’s natural resources as possible.

The UN had originally been designed to negotiate differences between a few relatively sophisticated countries. Decolonization rapidly expanded the UN’s membership beyond anyone’s expectations. The UN’s charter had been signed by just 29 countries. Today, a total of 193 countries are represented in the UN General Assembly. The level of political sophistication varies greatly among the membership. Instead of negotiating disputes between stable governments, the UN found itself increasingly having to deal with a new assortment of bloody tyrants. The colonial powers, especially Belgium’s King Leopold, who was guilty of barbarism in the Congo, had also been brutal, but the hasty withdrawal of the colonial administrations added chaos and unpredictability to the brutality.

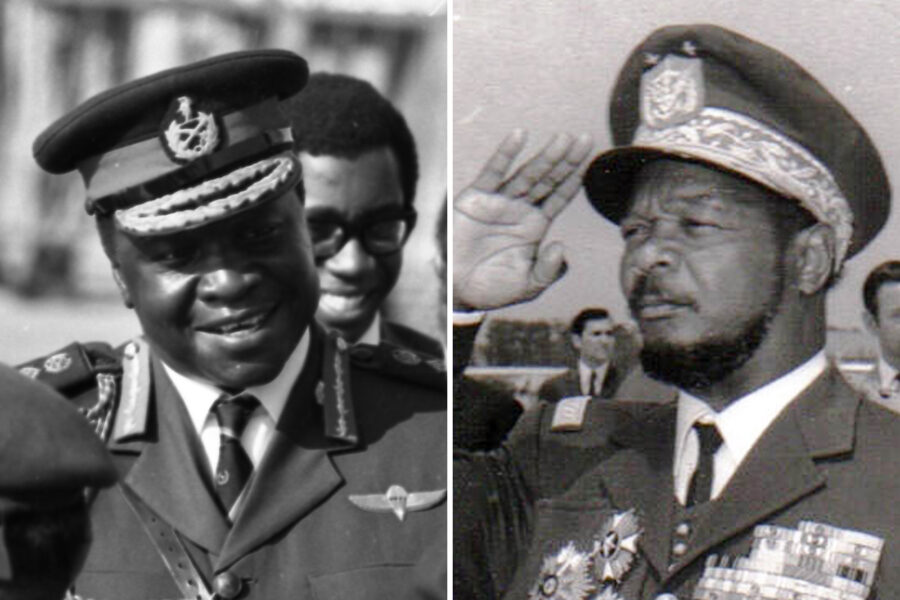

Idi Amin, an uneducated, semi-literate former army sergeant, seized power in Uganda and bragged about throwing opponents to the crocodiles. Jean-Bedel Bokassa, declared himself emperor of the Central African Republic and then boasted about serving human flesh to unsuspecting Western diplomats at his “coronation.” A host of minor characters imposed similar atrocities on vulnerable populations in a free-for-all to steal as many of the planet’s resources as possible.

The excesses of these individuals were compounded by the rise of criminal non-state actors and mass movements operating independently of any national government. Joseph Kony, the self-styled messiah of the Lord’s Liberation Army in Uganda, brutalized children, whom he forced to dismember their parents, in order to turn them into child soldiers. Terrorist groups ranging from al-Qaeda to ISIS began to influence geopolitics, but were hard to identify with any specific country.

The ICC, which attached responsibility to specific individuals rather than national governments, looked like a logical solution to a growing problem, but it quickly became apparent that different groups and situations can lead to radically different notions about what constitutes justifiable behavior. Former US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara admitted in Errol Morris’s 2003 documentary Fog of War that if the US had lost World War II, he (McNamara) and Curtis LeMay, who led the US strategic bombing campaign against Nazi Germany, would probably have been considered war criminals.

Laws tell us what we should and should not do, but in the real world, enforcing a court’s decision usually depends on political and military alliances. The partners in those alliances may be less than savory, and the enemy of your enemy can quickly become your friend. Iraq’s Saddam Hussein may have been a tyrant, yet when it came to restraining Ayatollah Khomeini’s personal brand of radical Islam, it was easy to embrace Saddam as a necessary ally.

Complicating the situation is the fact that laws are designed to place limits on power. It’s easy to see why many governments view the international courts as an obstacle rather than an ally. The US, having found itself by default serving as the world’s unofficial policeman in the half century after World War II, felt particularly vulnerable. When the ICC was first proposed, Washington made a major effort to keep the whole idea of the court from ever materializing.

The obvious concern was that major US figures like Henry Kissinger might find themselves accused of war crimes because of Vietnam and other foreign policy decisions.

Probably the ultimate issue for most Americans, however, is sovereignty. The US is simply not ready to let any organization outside the United States determine what we should or should not do. In the end, 124 countries joined the ICC. Roughly 40 did not. Egypt, Iran, Israel, Russia, Sudan, and Syria have signed the treaty, but never ratified it. The US, China, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iraq, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey never signed.

Once the ICC became a reality, it almost immediately found that the majority of the suspects it wanted to investigate were politically off limits. In the 22 years that it has been active, it has only managed to successfully try 31 cases. There have only been 10 convictions and four acquittals. Most of the cases have involved secondary figures. It is often easier to simply buy off a tyrant than to go through a lengthy legal process. In a number of cases, the targets of ICC indictments have simply died before the court could get around to dealing with them. Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi is a case in point. Gadhafi was indicted by the ICC, but was overthrown and killed before he could stand trial.

The vast majority of people the court has indicted have come from African countries south of the Sahara. That pattern changed in March when the court decided to indict Sergey Kobylash, the lieutenant general in charge of Russia’s long-range air force, and Viktor Sokolov, the admiral who commanded Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Those indictments were followed up with the indictment of Vladimir Putin on March 17.

The charges against Israel’s Netanyahu and his defense minister, Yoav Gallant, set a new benchmark since Israel often associates itself with Europe, yet the complaint was filed by South Africa. In a sense, the Third World was demanding that its voice be heard.

The indictments do not necessarily mean that anyone will actually be charged or will ever have to physically stand trial, but a conviction, and even an indictment, makes it difficult for the accused to travel to any of the 124 countries that recognize the ICC. When Vladimir Putin wanted to attend a conference in South Africa, he was forced into canceling the trip — not because he was afraid of being arrested, but because he wanted to avoid embarrassing the South Africans, who would have had to decide between not arresting him or offending the court.

The indictments of Netanyahu and Gallant, and the heads of Hamas, are likely to have a similar effect. Netanyahu can still travel to the US, but if he ignores the court, he will be blacklisted in most of Europe as well as much of the Third World. The Hamas leaders who were indicted can still travel to Iran and some of the Gulf states, but they run a risk if they go anywhere else.

The World Court’s ruling is different from the ICC’s. Although the order is to immediately stop the assault in Gaza, Israel has a month to comply by winding up its operations. The message gives Israel a chance to finish its business with Hamas, but sets a time limit on when the assault needs to be accomplished or simply ended.

In the end, the shift in the ICC’s focus from indicting African strongmen and renegades to taking on mainstream leaders like Putin and Netanyahu may signal that the kind of swashbuckling, “shoot-first-and-ask questions later” behavior that may be moving toward the establishment of global standards for civilized behavior. It also means that the most developed nations, the elite members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which replaced the post World War II Marshall fund, are no longer the only ones calling the shots.

The ICC’s prosecutor, who demanded arrest warrants against both Putin and Netanyahu, is Karim Ahmad Khan. Khan’s father is from Pakistan, but Khan was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, and educated at King’s College London and Oxford University. He is as British as they come, but with an obviously expanded perspective given his family’s origins.

Putin and Netanyahu may not care about the judgment of the World Court or the ICC. An Israeli complaint against the ICC is that it has put Israel’s campaign in Gaza on an equal footing with Hamas’s senselessly murderous attack on October 7. Hamas killed more than 1,200 Israelis. Israel’s retaliatory campaign has resulted in more than 36,000 dead Palestinians, most of whom had nothing to do with the October 7 attack, and the majority of whom were women and children. The only way the Israeli response and Hamas’s aggression can be seen as equal is if one considers the life of a Palestinian as having no meaning or value. Khan added the charge that Israel is effectively threatening to use famine as a decisive weapon against the more than 1 million Palestinians trapped in Gaza. That, Karim insists, is purely and simply a crime against humanity.

Netanyahu may argue that 36,000 dead Palestinians are nothing more than regrettable collateral damage, a by-product in Israel’s need to defend itself. But each of us needs to ask ourselves whether we really believe that. Israel, and for that matter, all of us, find ourselves forced to cohabit an increasingly crowded world. Eventually, what the rest of the world thinks does have an impact.

These are the questions that Karim and the judgments of the ICC and World Court are forcing us to consider. The fact that they are involved means that we can no longer simply look away from the problem. It’s up to each of us to decide how we feel about what is taking place and what kind of world we want to be in. To a certain extent Khan, South Africa, and the ICC and World Court deserve credit for forcing us to consider the question.