At the Front in Zaporizhzhia

Artillery has to a great extent replaced airpower in the current fighting in Ukraine. Both sides engage in a game of “shoot and scoot.” A Ukrainian battery opens fire on Russian positions, and then braces itself for return fire, hoping that camouflage will keep its location hidden from enemy drones flying overhead. WhoWhatWhy’s special correspondent Madeleine Kelly had a rare opportunity to spend several days with a Ukrainian unit at a front-line location where artillery duels have been among the most intense. This is her on-scene report.

|

Listen To This Story

|

We don’t get many chances to spend long periods of time with front-line Ukrainian soldiers, so this is a rare opportunity, especially since it means being briefly embedded with an artillery battery just a few miles from the Russian lines. Artillery duels are the key to much of the fighting in Ukraine at the moment.

We leave Kyiv at around noon and drive more than eight hours, arriving in Zaporizhzhia after dark. Bathed in the blue and white glow of an ATB supermarket sign, we hastily pile our equipment, cameras, sleeping bags, bulletproof vests, and helmets into the back of a minivan that has been spray-painted green, a kind of do-it-yourself camouflage. My body armor consists of a ballistic helmet and a black vest equipped with level-IV ceramic plates, which at least in theory can stop a direct hit from a 7.62mm “Black Tip” armor-piercing bullet. That is more protection than most police vests have in the US. My armor was provided free of charge at a HEFAT course (Hostile Environment and First Aid Training) that I took before moving to Kyiv.

We removed the press markings that identified us as journalists. We’d been told that they would only make us a target for Russian artillery. Besides myself, a fellow journalist and a fixer, as well as a young Ukrainian soldier returning from leave, also piled into the van. The driver, Dima, is a soldier, normally based in the area around Zaporizhzhia. He had been sent by the people we were due to meet.

We are headed for Orikhiv. When we reach the top of a hill overlooking the town, Dima pulls off the road and tells us it’s time to put on our armor. I ask him what the situation has been like lately. “Nothing good,” he says. Then he laughs to hide his pessimism. Orikhiv, nestled in a valley below us, is pitch black, but is briefly visible in the glow of explosions on the horizon. Flashes of orange and white reveal the silhouettes of bombed-out apartment blocks in a city that is dead. The flashes of illumination are followed by the distant thunder of artillery.

We take the body armor out of the back of the van and put it on. The young soldier who had accompanied us disappears into the darkness. As we drive past the city, our headlights reveal two young soldiers wearing body armor and carrying huge duffel bags that look almost as big as they are. I guess that they are preparing for a long tour of duty.

Dima drives the van under the awning of a gas station that had been bombed out. Shards of broken glass lie everywhere. I recognize the gas station and the road in front. A year ago, this two-lane road was a “green corridor” providing humanitarian safe passage for civilians shuttling back and forth between the Russian lines and Mariupol. A huge parking lot in Zaporizhia served as a staging area for civilians who wanted to go back into Russian-controlled areas. Some wanted to help their families. Some supported the Russians. Others didn’t really care one way or another. Many had to wait weeks for permission to reenter Russian-controlled territory. Towards the end of the summer, the Russians blasted the parking lot with a barrage of artillery killing dozens of people. That ended the humanitarian corridor.

We move our equipment from the van and put it in the trunk of a car that has been sent to collect us. Once the gear is safely stowed away, we are greeted by a tall, bearded Ukrainian soldier named Victor. He is there to take us to the front. We hastily say goodbye to Dima, who heads the van back to Zaporizhzhia. Victor, who prefers the nickname “Mustang,” has a jovial demeanor that tends to make you forget that this is increasingly dangerous territory.

When we finally reach the vicinity of the battery, Mustang parks the car and we walk through a forest until we reach a small clearing where Mustang gives us a brief tour of the site. At one end, wooden ammo boxes are used to store food where mice and other animals can’t reach it. At the other end earth has been piled up to make an ad hoc landfill. In front of us a trench has been dug into the earth. That will be our home for the next several days. A figure climbs out of the trench and approaches us. His name is also Dima, but he prefers to be called “Metro.”

Metro gives us a quick rundown on the rules for survival at the front. He then passes us headlamps with red lenses. The red light is mandatory at night. It’s harder for the Russians to spot, and using the red lamps also preserves your night vision, which vanishes as soon as you’re exposed to white light. “If you smell something different after a bomb goes off,” Metro warns us, “it could be artillery laced with chemicals. You can usually smell it in the air.”

As the night passes, I end up in the “command room.” This is a section of the trench with a roof constructed from tarps, logs, tree branches, compacted dirt, and assorted debris that provide camouflage. The walls are lined with silver-colored insulation. There are hooks for hanging guns, coats, and armored vests. A bed to the left is used by the commander who asked that we not use him in the story. Mustang’s bed is on the right. Two generators are stored under Mustang’s bed. A blanket serves as a door. Next to it are several shelves, which hold the Starlink router and several computer tablets that aren’t being used. At the opposite end of the room is a small green stool. Sometimes people sit on it, at other times it holds a computer tablet that taps into the network of overhead drones. All of us could fit in the command center, but it’s only big enough for two, or possibly three people to sleep. Metro sleeps in the open trench next to the room. We sleep in the trench next to him, exposed to the night air and whatever else happens to be coming down.

I can barely speak Ukrainian, and I string together a few toddler-like sentences to ask Mustang for a situation report so we can prepare ourselves for the rest of the night. “It should be quiet,” Mustang says. I feel tempted to knock on wood. It doesn’t work. I settle into my cot next to Metro, the others further along the trench.

A few hours pass, and then, at 3 a.m., we are all snapped awake by incoming artillery. I can hear the shells whistling through the trees above my head, then the blast. It’s close. It’s not the first time I have been exposed to artillery, but this time the shells keep coming, one after another. The walls of the trench tremble after each explosion. Dust and rocks come tumbling down around us. I curl into a small ball. Less surface for the shrapnel to hit, I tell myself. The truth is that I am curled into a small ball out of fear. I am like a child sheltering from a ferocious thunderstorm.

Finally, silence. As I blissfully drift back into sleep, a different, whirring sound grows in the distance. It grows louder. At first, I think it might be a small plane. Then a bomb explodes. It is so loud that the earth literally moves around us. Seconds later, another bomb explodes, this time even closer. This, I find out, is the latest Russian tactic. They strap two large bombs that would normally be carried by an airplane to an unmanned glider and send them off in the general direction of Ukrainian positions. The bombs are powerful enough to destroy anything in the trenches. The crater they leave is as deep as a two-story building. Survival, if you are hit by one, is impossible. Everything, survival included, comes down to luck.

Once the aerial bombs stop, I drift off to sleep again and I am then awakened by an ordinary Russian artillery barrage and the sound of Ukrainian guns firing back. I learn in the morning that we were a primary target for the Russians.

Now the artillery involves not just Western and Soviet-era howitzers, but also self-propelled artillery that can quickly change position in a game of proverbial “shoot and scoot.” The Ukrainians are trying to locate Russian positions, and there is a good chance of being caught in the cross-fire.

At 5 a.m., I hear Mustang talking from his side of the trench. I find my way into the command center. Mustang tells me that his team has been working through the night targeting Russians in the Robotyne area.

When there is a lull in the fighting, Mustang leaves the trench and brews some coffee over a camp stove. The soldiers subsist primarily on canned food, instant noodles, and lots of coffee, pretty much as many of them did in college.

Mustang enlisted in the army shortly after the Russians invaded. His wife and three children remained behind in Kharkiv. I asked him how often he takes fire like last night. In broken English, he says, “Last night was 9 or 10 on a scale of 10.” For some inexplicable reason that seems strangely reassuring.

As we are talking, Metro emerges from his slumber. He’s happy that there is nothing for him to do. Before we arrived, he explains, no one was hit with shrapnel, but one man had his face cut badly with flying splinters of wood. He laughs at the absurdity of the fact that that was his first work as a medic. Walking through the camp, Metro finds shrapnel scattered across the ground. That was a close call.

Back in the command center, the radio announces that the day is off to a new start. Drones overhead have spotted a Russian vehicle driving through an occupied village. Mustang is ordered to coordinate fire based on the stream of information broadcast by the drone. The team waits for coordinates and orders to begin firing.

On the tablet screen, we can see the car passing a checkpoint known as “the Block Post.” The car drops off its passenger, a Russian soldier, and then turns around to go back. Mustang orders the team to open fire. Seconds pass. There is tension in the air. The car passes Block Post 1. Suddenly the tablet shows a puff of smoke. The shell misses the car and it escapes.

Other targets have not been so lucky. “When I kill one,” says Mustang, “I send the video to my friends.” Mustang shows us a group chat. It’s filled with drone videos. The team’s strikes are usually extremely precise, a fact that is not lost on the Russians. Artillery has to a large extent filled the gap left created by Ukraine’s lack of air superiority.

Medics like Metro are left on both sides to patch the wounds created by hot metal shrapnel ripping through the flesh of men cowering in the trenches. Before the war, Metro worked on early intervention for children suffering from disabilities. His wife is a medic in the same brigade, but a different platoon. After his first deployment to the front line, they decided to get married before he went back. “We were walking our dog,” he says, “and then we just went to the city hall and got married.”

The rest of the morning is uneventful. Then finally we get to visit the D-30 howitzer, known simply as “the gun.” Wearing our body armor and helmets, we head down a hill, following a twisting path through the forest. The crew is wary concerning our presence, but nevertheless maneuvers the gun. I crawl into the trench behind the gun to take a photo. The blast from the gun hurls dirt and netting into my face and mouth. My teeth are coated in dirt. There is nothing special about the gun, except that it is a Soviet vintage howitzer from the 1960s that fires 122-mm shells. It is on a chassis with three feet set on concrete that is buried underground for stability. The wheel that elevates it was damaged in shelling the night before and is hard to move.

With the mission over, the gun crew quickly covers the gun with camouflage netting to hide it from the drones. We haven’t seen any, but no one doubts that they are there. Drones define the war. They provide surveillance, kamikaze attacks, and psychological terror. They are strewn across social media which is filled with videos of drones dropping grenades and carrying out suicide missions as well as providing precise information for artillery. Their importance cannot be overstated.

Back at the command center, Mustang watches Russian forces observed by a gaggle of Ukrainian drones that enable him to keep watch over enemy positions. He uses two tablets. One has a map and gives coordinates. The other one lets him toggle between 16 different angles that let him effectively see the entire area in real-time.

Mustang knows that the Russians are doing the same thing. Later in the day, we spot a Russian “Orlan” drone flying a reconnaissance mission over the trees. It looks like a tiny model airplane. Its motor makes a soft, barely audible buzzing sound. The Orlan is nevertheless capable of short-range and long-range surveillance. It’s inexpensive to produce and very effective on the battlefield.

As the day passes, the men use their downtime to video chat with family and friends. Mustang jokingly refers to us as the paparazzi. Every now and then the whistling sound of an incoming shell forces everyone to dive for the trenches. The next day tedium sets in. Metro says that he has read at least 12 books this year to pass the time.

While we are waiting for our ride out of the area, a new artillery barrage delays our departure. This one strikes so close that a shard of shrapnel lands at my feet after ricocheting off a tree above us. There is a moment of fear, but it passes quickly. It’s easy to fall into the habit of dismissing what might happen when you’re at the front. Soldiers adapt quickly. Mustang and Metro are veterans of the trenches. Both Mustang and Metro have a calming influence on us newbies. Metro still ducks but is otherwise calm. Mustang likes to say, “When I run, you run.” He rarely runs.

Before we leave, I ask Metro what he looks forward to most once the war is over. “I hope to just stay alive,” he says. “After that, there is no plan.”

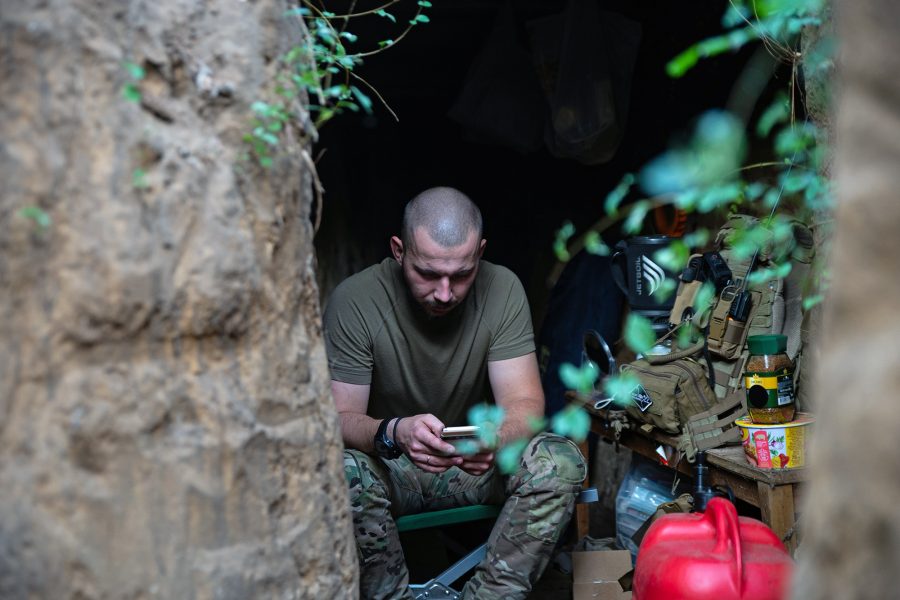

trench along the southern front. Soldiers along the frontline take shelter

from artillery barrages in the trenches. Photo credit: Madeleine Kelly / WhoWhatWhy