Among the Recounters in One Curious County

All Eyes Are on Wisconsin But Recounters Are Anonymous Faces in a Crowd

A lot is riding on the volunteers and officials conducting recounts in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. This election has revealed that the US election system is broken, but these Americans represent what remains right.

Every morning, Marti Faignant takes her seat at a folding table under fluorescent lighting in the Outagamie County Highway Department building. She is a volunteer in the giant presidential vote recount effort that is unfolding in rooms just like this across Wisconsin.

Normally, Faignant spends her time with her grandchildren or quilting, though her schedule has been a bit crowded over the last week.

Long before harsh questions fell on her community, Marti Faignant has always been there to help. She is a retired ER nurse, originally from Pittsburgh, who moved to a small town in Outagamie County where her husband was transferred.

She’s nonchalant about being a part of history — “It gives me something to do,” she toldWhoWhatWhy — but if there’s a central nerve point in the recount, Outagamie may well be it.

The quaint explanation from the county clerk: Someone pressed the wrong tabs on a handheld calculator.

Four years ago Mitt Romney won 50% of the vote, and Barack Obama 48% in this easterncounty. But the 2016 vote was nothing short of a landslide, with Donald Trump topping Hillary Clinton by 13 points.

Astoundingly, Romney’s 1,700-vote margin from 2012 ballooned to nearly 12,000 votes this time around — among roughly 94,000 votes cast.

Few counties anywhere have seen such a surge, catching the attention of Green Party officials behind the recount effort, and other officials and experts monitoring it.

Consider this: as of Tuesday afternoon, Trump and Clinton were separated by 22,177 votes inWisconsin. More than half that gap is rooted in Outagamie alone.

On election night, Faignant’s own hometown of Hortonville initially awarded Trump more than 1,000 phantom votes before the mistake was apparently caught the next day.

The quaint explanation from the county clerk: Someone pressed the wrong tabs on a handheld calculator.

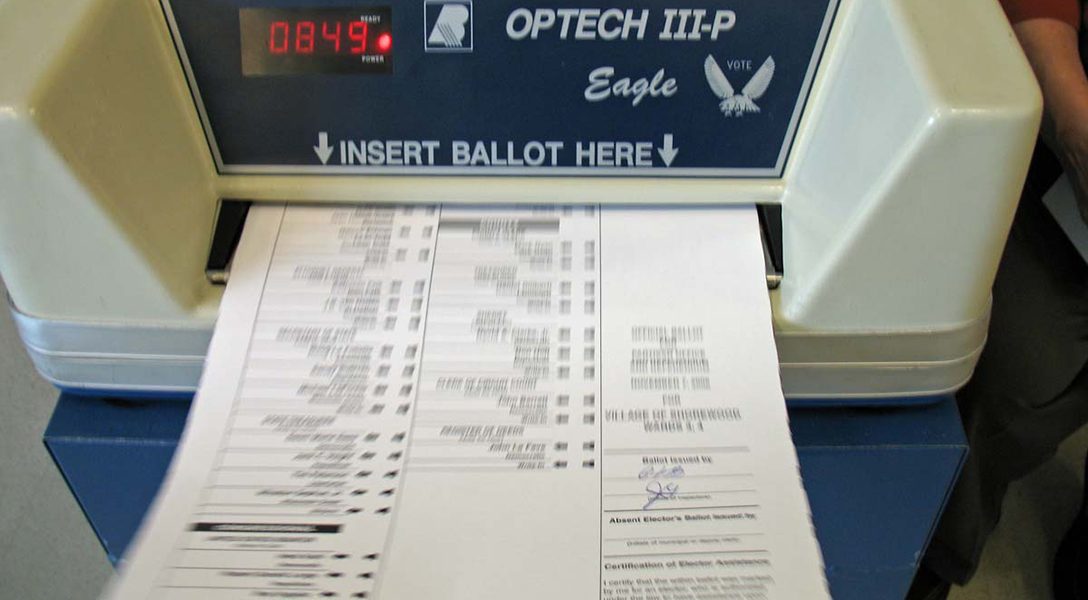

The Stein and Clinton campaigns wanted a hand recount because they felt it gave them the best chance of reversing the result. When a judge ruled last week that counties had the option of using optical scanners instead, this strategy was dealt a blow.

Places like Outagamie brushed aside the option of conducting a recount by hand — regarded by experts as the most reliable method — and chose instead to feed the ballots back into optical scanners, essentially repeating the process that tabulated them in the first place.

Recounting is a meticulous, multi-step process: (1) First, the ballot containers are examined toensure they haven’t been tampered with. (2) Then, “probable absentee ballots” are set aside and counted to see if the total matches with the number recorded on Election Night. (3)Afterwards, workers count the rest of the ballots to make sure those numbers conform with the number of voters in each ward. (4) In addition, Wisconsin state elections officials toldWhoWhatWhy that each ballot is examined by hand for any obvious problems, such as improperly completed ovals on the form. (5) They then set aside any ballot that seems problematic for hand recount, even in counties that scan the ballots.

Only then are the votes for each candidate counted.

Outsourcing to Machines

Outagamie County Clerk Lori O’Bright, faced with getting it all done by Dec. 12th, has no issue with using the optical scanners.

“When you have seven ballot candidates as well as registered write-ins, [machines] can tabulate more accurately, ballot by ballot, in an efficient manner in order for us to get done with the recount by the deadline.”

Over the last several days, a kind of stoicism has set in with the people assembled in the highway department building in Appleton. Even Nettie McGee, the Stein representative on handdidn’t feel this recount effort would alter the landscape.

“This is a waste of money. We’re not going to find anything,” she told WhoWhatWhy.

On a recent afternoon, McGee stood behind the tabulators, clutching a clipboard to her chest. Each campaign has observers standing over those handling the ballots on the alert for even ahint of a discrepancy on any single vote.

Likewise, candidates are authorized to have their own campaign observers acting as watchdogs, sometimes leading to crowded conditions. In Outagamie’s recount hub, there were sometimes about 40 people in a space the size of a large conference room.

McGee wasn’t worried about voter fraud or a cyber-attack affecting the outcome of the 2016 election.

“I’m here because someone has to be here,” she said.

A few people not involved in the process were permitted to watch from behind yellow tape and retractable barricades.

At one point, O’Bright turned on the speakerphone for everyone in the room to hear her conversation with the Wisconsin Election Commission. Eleven ballots from neighboring Winnebago County were discovered in one of Outagamie’s containers, and she was seekingpermission to move those ballots back to Winnebago.

After several questions, the commission gave the green light to O’Bright’s request.

“I just wanted to show that we are transparent in what we do and that we aren’t moving ballots to [mess with the count],” said O’Bright.

The Trump and Clinton observers were easily more civil with one another than their candidates had been. Two Trump observers were sitting behind the barricades, one busy on his laptop, when a Clinton observer popped in with a question.

“Hey, what’s up with your candidate suing to stop the recount?” said the Clinton observer.

“Oh it’s just the Super PACs,” replied one of the Trump men, and they shared a small laugh.

At 7 p.m., the recount apparatus in Outagamie County began to simmer down for the day. Marti Faignant grabbed her coat as she readied to head home on a crisp Wisconsin winter night. She doesn’t understand why the recount is being done, she said, but still, she insisted it is important.

“This is gonna show that our election system here, at least in Wisconsin, is honest and on the up-and-up,” she said. “Too bad we had to go through this to prove it.”