Rushdie Has Survived. Will Freedom of Speech?

Living in censorious times.

|

Listen To This Story

|

The last time I stole a book was from the Housing Works Bookstore Café in downtown New York, about 18 years ago.

The person I stole it for was Salman Rushdie.

The book was my own Satanic Nurses, a collection of literary parodies that included one of his own style, and since I didn’t have a copy on me, I pinched the volume off the store’s shelves and presented it to the bemused author, who had unexpectedly turned up in one of my favorite New York haunts.

We had our picture snapped together, a gravelly photograph that looks like it was taken on a box camera made out of sandpaper. I had the vague idea that this image released to the press would somehow spike sales of my work, but my publisher was more sanguine about it, and was proved right.

But Rushdie was a good sport about the whole thing, and he looks happy enough in the picture to have been buttonholed by a fan who had satirized him in print along with the likes of Norman Mailer, J.D. Salinger, Virginia Woolf, and P.G. Wodehouse (good company).

There has always been something courtly and slightly noblesse oblige about Rushdie, an early proponent of humblebrag. He’s known his worth for a long time now, as well as being constantly aware of his dangerous situation. The stress of living under a perpetual death threat tends to focus the mind.

After he was attacked and almost killed last August he all but disappeared from view (after being a “man about town” in New York for close to two decades). He reappeared recently in the New Yorker to give us an update on his condition and promote his new novel, Victory City.

He lost sight in one eye and one of his hands is “incapacitated.” His injuries continue to make it difficult for him to write, but I doubt they will stop him.

It’s not always true that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. But in Rushdie’s case, nothing has ever thwarted either his ambition or his determination to express himself. He’s gotten this far, he’s not about to back down now.

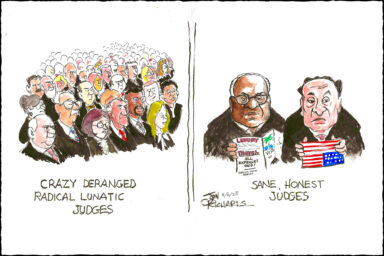

Rushdie’s courage is in marked contrast to the legislative cowardice lately demonstrated throughout the United States. We are not living in a particularly edifying era of free expression. Words, ideas, points of view are all regarded with suspicion.

In Florida, a bill making its way through the legislature would gut protections on free speech, making it harder to criticize public figures. The same state currently bars teachers from discussing sexual orientation or gender identity because of the controversial “don’t say gay” bill passed last year.

PEN America reports that book bans are increasing, with the number topping 2,532 in school districts across the country last year.

PEN America reports that book bans are increasing, with the number topping 2,532 in school districts across the country last year.

On the Left — traditionally more hospitable to free speech — the trans issue has shown activists trying to shut down differing views, labeling anyone who disagrees with them as “anti trans” or the work of “TERFs” (trans-exclusionary radical feminists). Even those who refuse to denounce these perceived infidels are themselves denounced.

Writers who dare to write about subjects not deemed to be part of their immediate experience or cultural heritage can have their books withdrawn by publishers cowed by social media outrage.

I’m hoping this is a temporary phenomenon, a pendulum swing soon heading back in the other direction. With the country seemingly more divided than at any time since the Civil War, free speech is in everyone’s interest, to allow for the open exchange of ideas and the freedom of discourse.

Of course, the removal of books from shelves isn’t always done for reasons of censorship. I remember the St. Mark’s Bookshop in the East Village used to have the work of their most popular authors, such as Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, and William Burroughs, stored behind the counter. This wasn’t because they were controversial, but because their titles were the most likely to get stolen.

Rushdie never got back to me, perhaps because he didn’t appreciate the parody. But he’s been busy over the years, and authors tend not to like getting dinged about their style. Sherwood Anderson never forgave Ernest Hemingway for parodying his work in The Torrents of Spring (1926).

In any case, I welcome Rushdie’s reemergence, and hope to run into him again some day. His resilience gives me hope for the future of free expression. All it takes is a little courage.

J.B. Miller is an American writer living in England, and is the author of My Life in Action Painting and The Satanic Nurses and Other Literary Parodies.