Remembering the Holocaust Is Not Enough

Slipping into an era of intolerance.

|

Listen To This Story

|

There’s a sequence in Ken Burns’s elegiac The Civil War series in which he recounts the many glass-plate photographs taken by Mathew Brady’s studio of the battle locations in Vicksburg, Gettysburg, and Antietam.

During the war there was a brisk trade in these images, but afterwards, no one was interested. People didn’t want to be reminded of the terrible slaughter that had rupturedt the nation and hollowed out a generation.

With no other recourse, the studio sold the plates for the glass, and people used them to build their greenhouses. Over the years the sun caused the images to fade, until eventually they were burned out completely, and an important record of the war was lost forever.

I’ve often thought of those images when I consider the Holocaust and the dwindling number of survivors still living and able to give us first-hand accounts of the sadistic and inhuman catastrophe they lived through. Seventy-eight years after the end of World War II, we are already forgetting our history, in many cases willfully.

I’ve been watching Ken Burns’s recent documentary The U.S. and the Holocaust, and it’s sobering viewing, partly because of the shock of recognition: It reminds me of our current situation, with rising intolerance of refugees and increasing assaults on Jews and other minority groups.

The Anti-Defamation League reports the number of Americans harboring “extensive antisemitic prejudice” has doubled since 2019. In 2021 (the last year fully assessed), antisemitic incidents reached an all-time high across the US, totalling 2,717 cases of assault, harassment and vandalism tracked by the ADL. This is the highest number since the organization started collecting data in 1979.

Some Jewish families are actually contemplating leaving the US to find a more hospitable country. This is a shameful commentary on what Americans are allowing to happen in what was once a proud beacon of freedom and tolerance.

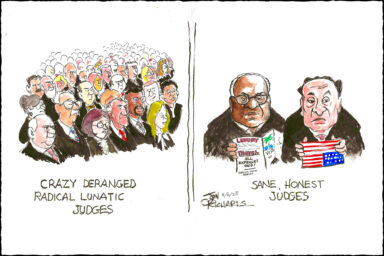

“Freedom” is a word thrown around a lot by Republicans, but its definition has become bastardized to mean freedom to own semi-automatic weapons, freedom to ban books they don’t like, and freedom to impose their religious edicts on others. “Tolerance” is barely in their lexicon.

We all know about Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s (R-GA) insane claim about a California wildfire started by “a laser” beamed from space and controlled by a prominent Jewish banking family.

When PBS asked 57 Republican members of Congress to comment on Trump’s dining with antisemite Kanye West and white nationalist and Holocaust denier Nick Fuentes, the great majority of them couldn’t even be bothered to respond.

One who did was Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, who remarked, “President Trump hosting racist antisemites for dinner encourages other racist antisemites. These attitudes are immoral and should not be entertained.” He added hopefully, “This is not the Republican Party.” This was a stronger quote than most of his brethren, but clearly this is the Republican Party.

Holocaust denial is unfortunately less surprising when viewed in context with election and climate denial. When people refuse to acknowledge the climate catastrophes happening now in their own environment, how are they expected to imagine a horror that occurred on another continent 80 years ago? It’s willful ignorance, the politically generated closing of the American mind that will have consequences for years to come.

After the Pittsburgh synagogue gun attack in 2018, Vice President Mike Pence refused to acknowledge any connection between the massacre and heated political rhetoric. (As I write this, the second California gun massacre in three days has been reported, and it produces something of a double take. “Didn’t I already read about this? Oh, it’s another one.”)

The phrase “Never Again,” supposedly uttered by the liberated prisoners of Buchenwald in April 1945, became associated with Holocaust remembrance, but it could just as easily be applied to the gun control movement, a campaign as challenged as that for tolerance.

The term “The Holocaust” itself wasn’t in wide use until the 1960s. After the war, as in the post–Civil War era, people didn’t want to focus on the traumatizing event. But gradually, as the scope of the slaughter and its shocking sadism became apparent, there was a general remorse about how the world let it happen. But the United States’ failing in welcoming more Jewish refugees from Europe well after the truth of the death camps had become known has been news to many Americans, with Burns’s 2022 documentary a revelation.

According to a Pew Research Center poll, more than three times as many Democrats as Republicans say it’s “very important” to take in refugees (41% to 13%).

In the UK, where I live, the current government is trying to make it more difficult for refugees to apply for asylum, categorizing them the same as illegal immigrants seeking to move here for economic reasons.

As we commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day, our ability to remember is sadly fading as much as those images on Brady’s glass plates.

—

J.B. Miller is an American writer living in England, and is the author of My Life in Action Painting and The Satanic Nurses and Other Literary Parodies.