We Keep Dragging Ourselves Through This Hole in the Sky

The obscure meaning of a total solar eclipse.

|

Listen To This Story

|

The eclipse was coming to my hometown. This gave me an advantage in writing about the transcendent experience of watching the heavenly spheres align. So much of what was going to happen in the sky was uncanny, but at least I knew what the ground would be like.

I grew up in San Antonio. The prevailing wisdom is that nothing has happened in San Antonio since 1836. Now something was finally happening again and I didn’t want to miss it, this apocalyptic thing changing the nature of all these familiar things. My elementary school plunged into darkness. My favorite drainage culvert to play in, plunged into darkness. So many things and types of things.

I would’ve come to San Antonio for the eclipse, but then my stepfather died suddenly a few weeks before. Stood up and fell down in the house and that was that. The house was now another familiar thing that had become strange, due to the presence of his absence.

I spent a week and a half in San Antonio for a memorial and then a funeral out in Fort Stockton, on a ranch that sits inside the 100-million-year-old crater of a meteorite strike. An astrobleme, they call it. A wound from the stars. All the family and family friends I hadn’t seen in years, all of us looking for something to talk about, and I’d say I was going to be here for the eclipse anyway. That’s what I kept saying: I was going to be here for the eclipse anyway. Like an idiot. Like his death had anything to do with anything. Like I’d taken advantage of some convenient overlap of celestial scheduling. Which maybe I had.

We — my wife and I — had gone to Jackson, WY, to see the total eclipse in 2017, biking out to a sandbar along the Snake River. Like a lot of people, we decided then and there to see every total eclipse we could, which we promptly forgot, except for this one, the one going through my hometown, which was conveniently located. We were going to be here for the eclipse anyway.

After the funeral, we came home to Los Angeles for a week, and then we returned a few days before the total eclipse. We had lunch at a restaurant with my mother and father and stepmother, who are all friends. We sat out on the patio, under a large umbrella, and had to keep shifting our seats to stay out of the sun. Mom was in good spirits.

I don’t know that I expected things to be different from last week. I continue to be disappointed in my expectations of grief. As a kid, before anyone I knew had died, I assumed grief was as depicted in movies and books. Crying, and desperate clinging. But mostly what it is, is: logistics. A lot of planning and a lot of moving trays of finger foods around. My wife is the only person I know who grieves in the way I’d expected, with tears and open feeling. Possibly that’s because she’s emotionally healthy. Or it’s because she’s a working actor.

San Antonio has a few things going for it, including the total eclipse. But perhaps the best thing to me is the live oaks. The shade of a live oak is the best of the tree shades. That is my opinion, of course. Perhaps syrup farmers in Vermont think maple shade is the best shade, but what else would they say? Their livelihood depends on it. I say the live oak shade is the best shade and I’m not paid to say so. The trees gently loom and the quality of the darkness is soft like green suede. I hate to say dappled because that is a static word. A painter’s word. The oak shade, though, it murmurs. If the shade were sound, it would be the distinct but ambient conversation of a well-worn cocktail party that has stretched into the night.

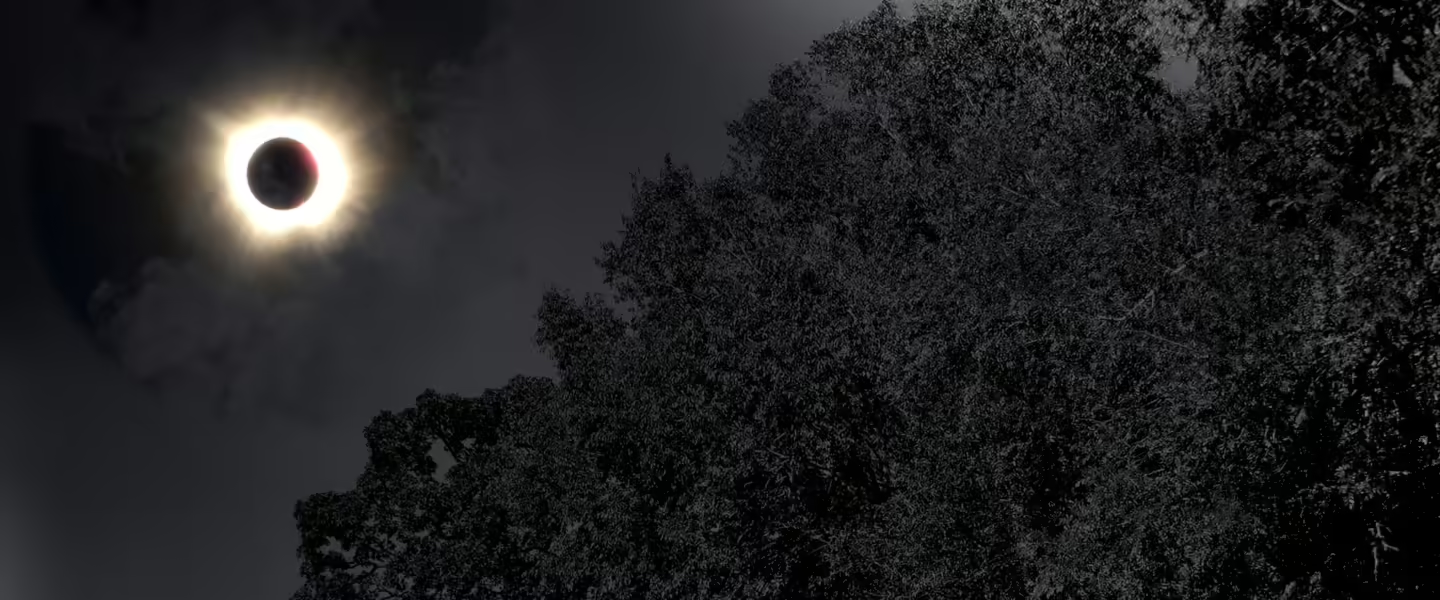

I was excited to gather the family together for the eclipse. I had imagined it as a transformative experience since seeing the eclipse in 2017. In Jackson, on the Snake River, the sun even in partial eclipse carried on as it always had, until the sky darkened and it stopped being this ambient source of light and heat and seemed, really, truly, like something with sudden proximity, a nightlight plugged into an indigo wall, and I had the primate instinct to reach out and try to grab this strange thing just as I had done as a child on a Texas beach with a Portuguese man o’ war.

I realized then that you could safely look directly at the sun during totality, but I’d been made so paranoid of burning my retinas that I only glanced at it, mostly averting my eyes as in the encounter with the godhead. It seemed more dangerous to look at it when it was dark, seductively so, radiating a peaceful but terrifying light — the danger not overt but the familiar and human danger of addiction.

And yet when I finally did stare right at it, it was merely transcendent. It only changed forever my understanding of seeing.

So that’s the sort of thing I was looking for with my family, especially maybe now. They were like Sure, okay when I presented this. Fair enough. The shoals of coverage about the total eclipse all suffer from the same problem — how do you convey what’s significant about this experience? (Only Annie Dillard has managed it.) Words, mostly, fail. See above. Worse still is the imagery. I feel for the photo editors. It’s either people looking up with the corny glasses and hanging mouths, like a 1950s audience watching the world’s largest 3-D movie. Or it’s the eclipse itself, which is worse — a dark spot with an outline. If the eclipse photo was a sound, it would be a trombone blast.

No, the most realistic coverage is not the Mystery. It is the logistics — traffic, eyewear. A lot like grief in that way.

Now I think about it, it’s entirely possible that my family has always been so subdued because of allergies. Texas is tremendous in its allergens. My stepfather’s death coincided with the most aggressive phase of live oak pollination season. Anyone foolish enough to stand still for more than 30 seconds would be dusted with a chartreuse coating of pure arboreal desire. At night the trees and grass, ticking. All this pollen causing headaches and spontaneous, startling naps, which is how our primate bodies react to what I’m sorry to say can only be called a botanical fuck-fest.

Nature, in other words, is strange enough even without astronomical phenomena.

But now, days before the eclipse, the oaks had mostly gotten all this sordid business out of their system. Still, we were all subdued, discussing the only part of the eclipse guaranteed to be apocalyptic, the traffic. This while our feelings about things ran underneath. Processing death at the end of this great tree orgy. The insistent upward pressure of meaning against the bottoms of our feet, or the events from the past exerting a forward pressure to mean something into the future.

As it happened, there was an air show the day before the eclipse. My father and brother and I went. My stepbrother — one of my stepmother’s sons — is in the reserves and was showing off the C-5 like a model home. (I have step-folk littering the American and Global South.)

Leaving early, we entered a sudden traffic jam. We were in a traffic jam, staring up at fantastic phenomena in the sky. I experienced it as though it was already a memory that I was recalling far into the future, but misremembering key details; not Monday but Sunday, the traffic brought to a standstill not by a total solar eclipse, but by Air Force stunt team the Thunderbirds.

Thus my anxiety going into Monday. Into the day of the eclipse, in which I must somehow wrangle my family to a place where the persistent cloud layer would break and we’d all, together, have this experience like the Jackson experience, the nightlight as big as the world.

Someone had taken NASA’s data and created an interactive map online. You plug in an address and it will tell you how long that point will be in totality, rounded to the nearest 30 seconds. This creates all sorts of other factors, like is it worth spending an extra maybe hour in traffic (each way) to gain another half-minute of totality? How much time is required for the experience to achieve whatever it is we’re looking for it to achieve?

How many seconds do you need to spend in that umbra until your default-mode network goes quiet, the psychic boundaries of the self dissolve into the vibrating darkness that passes over and through you at 1,600 miles an hour — a darkness in motion that can’t be felt, in which speed becomes substance, just night roaring by imperceptibly?

And so these familiar places in and around where I was born take on different, higher meanings: Downtown, where I went to prom, will be in a partial eclipse. That makes it essentially worthless. But Hondo, where our family once had a little scrubby property, will have nearly 3 1/2 minutes of totality. It therefore contains more of the dark matter of transcendence than the house I grew up in in Leon Valley, which is only in totality for maybe a minute 45.

Is it “better,” say, to go to a familiar place even if it’s less time, because all those familiar sights recontextualized are more transformative than spending more time in a place you’ve never seen before? And if you’re stuck in traffic for hours, does that detract from the experience, even just by weighting the story forevermore with an annoying caveat?

It becomes about logistics and not mystery; it becomes about calculation and not spirit; it becomes about trying to manage the ineffable, and in that way the shadow that swallows the world is its own kind of grief.

My dad ended up having to work. My wife ended up having to suddenly fly back home. My brother ended up deciding he’d rather stick to his routine and go back to his house. My mom and stepmother both said Sure, okay, which was the exact attitude of the weather that day. Sure, okay. The clouds, eh, they meandered, and maybe the sun fell out occasionally in a way that unfortunately registered with me as the same haphazard and irritating manner of an ugly man’s robe coming undone over and over. When the partial eclipse began, I abandoned the pretense of transcendence and chose the parking lot of an Italian restaurant with a ridiculous name, Skuzzy’s or something, along Loop 1604, high enough to afford a view of the west and south.

My mom and I drove together; my stepmother met us there. Logistics. The clouds flopped around. Come on already. Other people were sitting in lawn chairs in the parking lot, leaned back and watching a 3-D movie of nothing special. What if this were the apocalypse? What if this were the rapture? Those holy few would slouch up to heaven, shrugging. Is how I felt.

I brought special, non-stupid eclipse glasses through which we could see nothing at all. My mother took hers off. “I can see! It’s a miracle,” she said.

By and by, the sky went from the gray of an overcast day to a suspiciously darker gray, and then an uncanny one that seemed to be more in the head than in the sky, and then it was dark, at about 1:31 p.m. local time. “Well, this is it,” I said.

Mother and stepmother both said Sure, okay, and then chatted for a while about socialized medicine and sobriety. Someone walked by with a black-and-white dog, and my mom’s eyes grew wide. “Ooh, look at that dog,” she said, transported.

It wasn’t disappointing because it had no comparison. Some thousands or hundreds of thousands of people that day would feel a religiosity or a transcendence or a terror, and their lives would be changed, the old life caught up in the pressure wave of the shadow, suspended for a minute or up to four and a half minutes and lit by the perfect silver ring of the nightlight, and then their old life would be carried away on the shadow’s eastward ebb. They’d all stand there blinking at one another in the dawn of their new lives.

That wasn’t us in that parking lot. It just got dark. When the parking lot lights were tricked on, somebody gasped or moaned. That’s how low the standards were on that hill.

The darkness shrugged away and the light wandered back. People packed up and left. My mother and stepmother discussed plans for the coming days. Since my stepfather’s death, my mom hadn’t been particularly active, but now she was going to get some Botox. “I figure I must be healing,” she said of her new life, smiling.

For the rest of the day, I went around blinking rapidly at everyone, convinced I had burned my retinas in a moment when the eclipsing sun stumbled out of the clouds. I blinked rapidly at the barista and I blinked rapidly at the guy at the Goodwill to whom I delivered a shoal of my stepfather’s books on John Wayne, Western history, and Clinton conspiracies. I went around blinking rapidly, chasing a tiny, possibly imaginary crescent around my field of vision. Wondering if I’ll now carry a sliver of this moment of my life punched into the back of my eye like a tin nightlight, projecting moons and stars on a bedroom wall. Adjusting to the idea that this is how the world will look, forever.