Is Journalism Inevitable?

Tilling the soil in search of news.

|

Listen To This Story

|

More bad news: We have lost another newspaper. This time it is the St. Louis Riverfront Times, a venerable alt-weekly that for 46 years covered the city’s culture and politics and had an appetite for investigative journalism. It was sold to “an undisclosed buyer,” which is never a good sign, and the entire staff laid off.

“While somebody has purchased the RFT, it’s not going to be what the RFT was,” Executive Editor Sarah Fenske told St. Louis Public Radio. “My best guess is that this is just going to be one of those websites that is a shell of its former self. That’s devastating for St. Louis journalism.”

In memoriam, a former RFT reporter named Monica Obradovic posted some of her favorite stories from the paper’s star writers. They exemplify the range of coverage and tone, and vivid strangeness, of a good alt: a naked bike ride, the polluted River des Peres, an all-you-can-drink bar measure, a killing by police. Informed and critical and conversational, the stories from a good alt-weekly feel like they come from that brilliant friend who sometimes goes missing for days on end, to some frontier or other.

It is an eerie thing to look at the RFT’s website and as of yet see no mention of its own demise, as though the shockwave hasn’t reached it yet.

One more outlet, almost surely gone, or soon to be transformed from a beating heart or liver or kidney of news to something more like a spleen, performing a function but not exactly keeping the body politic alive.

I was talking to my mother a few days ago and she told me she was going to once again subscribe to her local paper, the San Antonio Express-News, on Sunday, for the obits, “to see who’s dead.” This is something I’ve noticed the Boomers do — read up on which old friend or former lover achieved a last moment of celebrity — and I always think it’s weird. But now I see I do the same thing, or a similar thing, checking in on which papers have died, and on the steady creep of death as recorded by UNC’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media’s “news desert” project. The difference between my mother’s moribund interest and my own is the difference between causes of mortality: In the obits you see cancer and heart disease; you do not see “death by rapacious hedge fund” or “murdered by idle billionaire looking to pad his portfolio.”

So let’s assume future closures, which — compounded by historically low public trust in media and, you know, the internet — means less actual newsmaking. As the lights on that map of news wink out, you have to wonder, or at least I do, what will take the place of the kind of information-gathering and distribution that journalism does. Will anything take its place?

Is journalism inevitable? Will methods of finding, synthesizing, and distributing truth naturally emerge in some form or another, regardless of social structure, or political regime, or economy? Does journalism “need” to happen for a society to work?

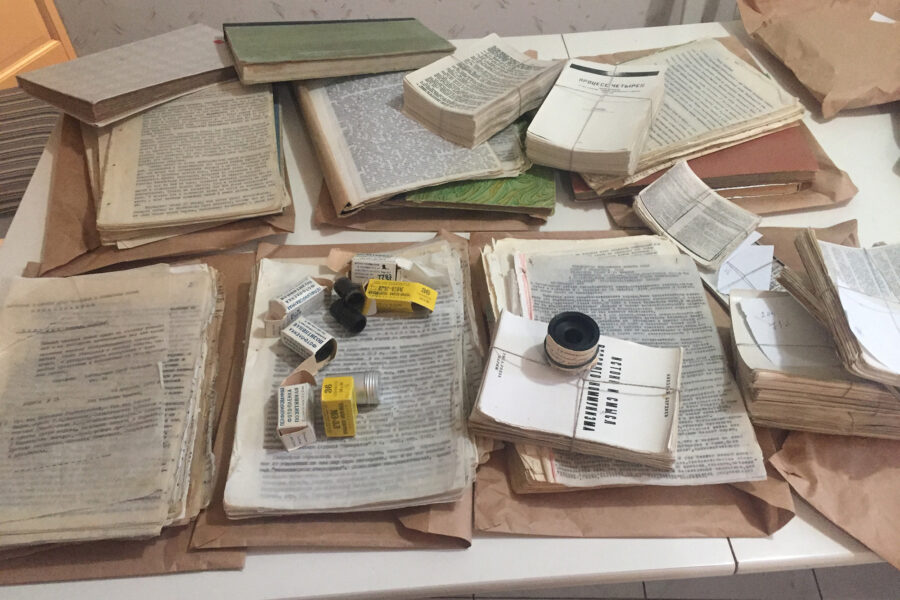

In the USSR, when the government and KGB restricted access to information, citizens created samizdat (Russian for “self-published”) to secretly distribute novels, poetry, political tracts, and philosophy in hand-typed and photocopied editions, passed from one person to the next. Samizdat also included Western popular music like rock and jazz that were bootlegged with tape recorders (magnitizdat) or pressed into records using old X-rays (roentgenizdat), which were called “bone records” or, delightfully, “ribs.” There was also a periodical called A Chronicle of Current Events that from 1968 to 1982 was a forbidden publication for the nascent human-rights movement in Russia.

Now, there’s a modern version of this underground distribution network, a media project called Samizdat Online created after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, when Putin’s security services restricted access to sources of real information. Samizdat Online “makes it possible to bypass the DNS [Domain Name System] blockades set up by autocratic regimes” so that readers in Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere can read journalism that their countries have blocked by generating, per Business Insider, “new, randomized domains for media outlets” so that readers can see “what is essentially a mirrored version of a publisher’s site or article.”

Samizdat is a parable for the beauty of truth growing improbably out of salted earth. It suggests that humans are wired to want and find and produce news, that it will happen despite the severity of the regime that tries to restrict it. I think I see this yearning for news in the proliferation of newsy entities all over the new media: informative stuff on YouTube and TikTok; on Twitter once upon a time and on X maybe still now; on podcasts and in newsletters. People — journalists and not — finding niches to talk about the kinds of esoteric things that might have shown up in the alt-weeklies.

Just one case in point: A YouTuber named Jenny Nicholson has gone viral for a four-hour video detailing the epic letdown of her visit to Disney’s Star Wars hotel.

Not exactly a deep-dive into fraud within a police department, but Nicholson demonstrates, as a 2022 Google study puts it, that Gen-Z viewers “are more willing than ever to indulge in hours-long video content covering topics close to their hearts.” Which may explain why, as one Pew survey found, the under-30s are “now almost as likely to trust information from social media sites as they are to trust information from national news outlets.” Another Pew survey found that half of US adults get at least some news from social media: While they like the convenience, speed, variety, and up-to-dateness, they worry about inaccuracy.

All of which is to say, social media seems a viable model for the future of journalism, and things like inaccuracy, while extremely worrisome, are not insurmountable obstacles when you have an American audience (or at least an American audience that responds to polls) expressing a real interest in news.

While a lot of that interest seems still to be focused on local news, according to just one more Pew poll, that number has fallen 15 percent since 2016. This makes sense, for a reason explained to me by WhoWhatWhy’s own news Jedi, Jeff Schechtman, who noted that there are basically two types of players thriving in the media space. There are the big-and-getting-bigger like The New York Times, and the extremely niche podcasts and newsletters and YouTube channels that survive (if they’re lucky) off subscribers and ad revenue. The core of the industry, occupied by mid-sized outlets like the Riverfront Times and dozens of other alt-weeklies and non-alt-weeklies, gets, as he says, “hollowed out.”

Those mid-tier papers and radio stations once thrived on local business ads and classifieds, but then something interesting happened: Big box chains like Home Depot and Walmart pushed out local hardware stores and groceries, which are exactly the kinds of businesses that once supported local news. That news vacuum has been filled by large, nationally focused outlets like the Times and of course cable news like Fox and MSNBC, which are themselves the big box stores of news. What’s weird is that those chains are exerting a metaphorical and literal effect on the character of towns and cities — national business replacing local business, which pushes out local news, replacing it with national news.

This has a homogenizing effect on places. Local politics are increasingly defined by the culture-war type issues of national politics, when really the president has much less effect on your life than does your city council. Everywhere, eventually, becomes anywhere.

More and more, coverage of local issues is left to busybodies on Facebook and gadabouts on Nextdoor. These dispatches have the same relationship to truth as a dog trying to snatch a fly out of the air — it’s clumsy, rarely successful, and only barely nourishing. Its appeal is that it kills time, and seems to make the dog happy.

So: Is journalism inevitable? It seems it will indeed grow in all sorts of soil. Some comes out stunted, or tiny, or specific and sprawling and Disney-focused, or wrong as hell. None of it, as yet, seems capable of replacing the lost Riverfront Timeses, or pulling all these diverse cities and towns and communities back from the brink of nationalized homogeneity.

The only other insight I can offer that is relevant to journalism’s inevitability is a factoid that goes almost unmentioned in the Pew study on local news. What is the most common source from which most people get their local news? “Friends, family, and neighbors,” to the tune of 73 percent, up from 66 percent just six years ago.

Sharing stories of the world with those closest to us, mouth to ear, is a social network so much older than computers or printing presses or agriculture, and it’s heartening that its influence seems to be growing. Now if we can just figure out how to monetize it.