Every Generation Throws a Toilet Up the Pop Charts

‘Skibidi Toilet’ is a meme, a made-up moral panic, and a YouTube blockbuster. But is it art?

|

Listen To This Story

|

Every generation has its power objects, those cultural totems that serve both to unify it and to alienate it from the previous generation. It’s a perfect reciprocating process: The more it alienates, the more it unifies.

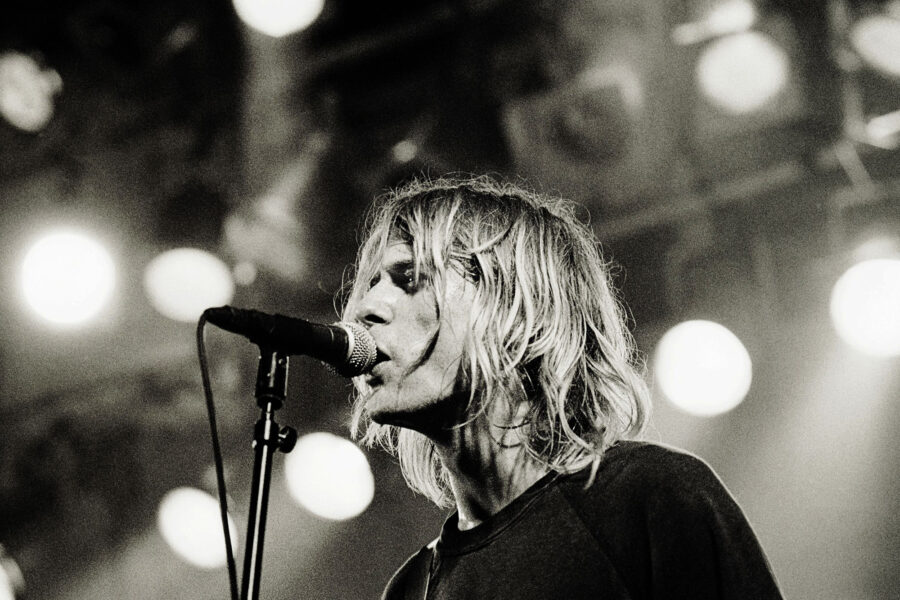

Gen X has Kurt Cobain, West Coast hip-hop, and thinly tweezed eyebrows. Millennials have avocado toast, “work to live,” and the color pink. Gen Z has Teletubbies, TikTok, and gender. The Baby Boomers, of course, have Elvis, the Beatles, Reagan, automobiles-as-pleasure-object, and basically anything that has annoyingly become synonymous with the core idea of “American culture.”

The latest generation’s moniker, settling like a collapsing souffle, is Alpha. Born in the early 2010s, these people are currently children. That fact has in no way impeded the flood of media stories trying to augur the nature and direction of this young generation from its use of slang like “gyat” and “Fanum tax.”

The “kids these days” beat is an old and venerable one in American journalism. Its reporting often takes the form of listicles that attempt to diagnose the generation through its neologisms. Older examples might drop you into the scene, but the tell is always the liberal use of quotation marks.

Here’s The Atlantic reporting on “hippies” in 1967:

The shops of the “hip” merchants were colorful and cordial. The “straight” merchants of Haight Street sold necessities, but the hip shops smelled of incense, the walls were hung with posters and paintings, and the counters were laden with thousands of items of non-utilitarian nonsense.

Contemporary accounts are valuable for recording the in-the-moment evolution of language around that generation, which usually involved what to call it.

Here’s the Los Angeles Times on what would become Gen X in 1991:

Much has been written about the so-called “baby buster” generation — the fairly anonymous group of 20ish young adults struggling to separate themselves from the shadow of the baby boomers. For the past few years the media has tried to pin a label on this demographic — but nothing seems to fit.

The group’s newest moniker, “the MTV generation,” might be the most accurate description yet.

And The Washington Post in 2008 trying to figure out what the generation after X was going to be called:

Complicating matters, millennials are sometimes known as generation Y. Then there’s the Facebook or YouTube generations. Echo boomers is also bandied about. The presidential campaign has spawned the Obama generation, a nod to Sen. Barack Obama’s reliance on young Democratic voters. …

“I don’t pay attention to labels,” said Kate Gersh, 28, a nonprofit grant writer and former White House intern. “I’ve never heard of millennials.”

(“Millennials” being a better name ultimately than Generation Why, Generation Atari, or Generation T, as in “T-shirt.”)

This journalism stokes intergenerational ire by reporting on cultural evidence proving that… time passes. The effect for readers older than the generation in question is a kind of FOMO — a millennial term that seems to have been spawned not in the mean streets of the internet, but at Harvard Business School. Not just any FOMO, but a cosmic one, the fear of missing out on the world as it moves beyond you. In extreme cases, you get ghosts — the effects of post-mortem FOMO.

The details of these stories conceal the terrible, reassuring truth: We’re all pretty much the same all the time. Every generation wants to free itself from control. Every generation wants to create something new. The circumstances change, but for a species that still hasn’t completely evolved to digest milk, it’s unlikely that a generation’s lingo is evidence of a paradigm shift. Does knowing that “Fanum tax” refers to a popular streamer’s habit of asking for food from friends, or that “gyat” means somebody’s got a big ass, tell you anything about how far things have come? Or is it just a familiar kind of trivia?

Something’s always distracting us. Something’s always endangering us. Something’s always pulling us away from the proper course of history as laid out by our elders.

***

Generation Alpha is currently defined in part by its relationship to a web series called Skibidi Toilet. This is a series launched on YouTube in February 2023 by a 25-year-old from Georgia (the country) named Alexey Gerasimov, who goes by the handle DaFuq!?Boom!. Briefly, the series concerns the ongoing war of an invading race of toilets with human heads emerging from the bowls against an insurgency of humanoids with CCTV cameras, televisions, or audio equipment for heads.

I can’t help that this sounds insane. I know. But unless you’re a very young member of Gen Alpha, you’ve probably encountered a case where the description of a thing in no way communicates its artistic power. “Seafaring obsessive pursues unusual whale, dies.” “Mopey prince wonders what it all means, dies.” “Guy spends a whole day in Irish city.” We could do this all day.

Gerasimov currently has more than 42 million subscribers on YouTube and views in the tens of billions.

Every news story that talks about Skibidi Toilet: 1) identifies it as a touchstone of Gen Alpha; and 2) attempts to explain its appeal amid various moral panics.

In the same way that all generational stories over the years tend to paint with a broad brush, Skibidi stories are confident in claiming that the series is a foundational text for Gen Alpha. Per a Mashable “parent’s guide to Skibidi Toilet”: “Gen Alpha (kids born after 2012) are Skibidi Toilet’s biggest fans, with some crossover into the youngest cohort of Gen Z.”

But I haven’t seen, for example, viewership numbers for the series broken down by age, which YouTube wouldn’t necessarily know (or share) anyway. KnowYourMeme suggests the Gen Alpha connection came from a Twitter user who in July 2023 posted, “Went down a YouTube shorts algorithm rabbithole and found out what Gen Alphas slenderman is” —

Went down a YouTube shorts algorithm rabbithole and found out what Gen Alphas slenderman is pic.twitter.com/Pydc1Ulnjv

— Soundgarten Of BanBan (@AnimeSerbia) July 9, 2023

— and since then, it has acquired the proportions of any good internet-driven moral panic.

You’ve got parents on Reddit begging for help after the “new genre of youtube video about evil singing toilets” scared a potty-training child so bad he “refuses to use the toilet now due to skibidi toilet,” even after they “let him decorate it with stickers.”

On the other hand, the media narrative tells us that the real problem seems to be that kids like it too much. This is how you get totally made up conditions like “Skibidi Toilet Syndrome,” as evidenced by a scattering of videos and mommy-blog posts (originating in Indonesia, so it seems) about children freaking out when they’re forbidden from watching the series; shrieking like Beatlemaniacs at Skibidi Toilet characters enlivening their parties; or worse, sitting in cardboard boxes or laundry baskets and singing the dreaded song.

Completing the arc of this fabricated saga, the Russian police are, allegedly, looking into it.

A Washington Post story by Taylor Lorenz says Skibidi Toilet’s “ascendance reveals what the future of entertainment might look like across major social platforms. It is the first narrative series to be told entirely through short-form video (60 seconds or less), and it’s the first major mainstream meme that has arisen from Generation Alpha.”

While Skibidi Toilet is presented to the American audience at large as evidence that the new kids are into some weird stuff, it is a crisis to the older kids — Gen Zers, whose native dominance of the internet is challenged by this series that even they don’t seem to understand. Per WaPo:

While Gen Zers initially appreciated the nostalgic gaming element of the series, many of them now feel uncomfortable and have made reaction videos and memes lamenting its growth.

Sophie Browning, 21, a content creator and meme account administrator, says that’s a natural reaction to Gen Z being supplanted as the driver of online culture. “This is the first time Gen Z feels old or out of touch with meme culture,” she said. “We’ve been told that we run memes and control what’s popular and funny, but now I think Gen Z is reckoning with the new Alphas. It’s unnerving for them to encounter this big meme phenomenon that they don’t feel a part of and didn’t contribute to.”

Maybe Skibidi Toilet really is Gen Alpha’s Friends. If so, how to explain its hold on a generation whose interests range from object permanence to driver’s ed? “The series’s main appeal to young minds seems to be its blend of potty humor and absurdity,” writes Elizabeth de Luna in the parents’ guide.

(It is worth mentioning that for all the toilets, there is no actual excreting or human waste in the series; the toilets are actually more like vehicles and bodies, and yes I hear myself and will let this go now.)

Nothing about Skibidi Toilet suggests Gerasimov designed it for children. That said, it can certainly be read as a Tom Clancy thriller for the post-diaper set. What, in Gen Alpha’s short life, has heretofore presented a greater personal and professional challenge than the toilet? It’s the first piece of infrastructure we learn to use, the first piece of technology whose mastery ushers us into a wider social world.

And, too, the cinematography reflects a child’s worldview: Each episode is a recording from the head-mounted CCTV of one of the cameramen protagonists running around this urban battlefield and often, especially in the early episodes, getting dispatched by one of the frightening toilet-heads lunging straight at the viewer. These cameramen are human-sized, but as the series progresses, larger and larger combatants are introduced, building-sized warriors on both sides. Such that, my point is, the viewer is often looking up at these huge adult figures that sweep in to save the day. What Freudian could deny this reading?

Perhaps you skew more modern. In that case, a HuffPost story that kicks around such disagreeable names as “Generation Glass” and (ugh) “screenagers” argues that:

Technology for Generation Alpha “is not something separate from themselves, but rather, an extension of their own consciousness and identity,” said Natalie Franke, the head of community at the business management platform HoneyBook. She believes many people in this generation may prefer the virtual world to the physical world and that they’ll also have more opportunities for creativity.

For a young generation of cyborgs, the appeal of humans joined with cameras and plumbing is obvious.

***

Confession: I love Skibidi Toilet. Why I embarked on this story in the first place was to articulate my confusion as to why so many journalists and social-media users treat the series as though it’s a gross and mystifying bug. It’s no weirder than, say, ’80s-icons-turned-valuable-IP like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (“Pet-store turtles in New York exposed to radioactive ooze fight secret New York ninja cult, eat pizza.”). It’s no weirder than pre-internet animation anthologies like MTV’s Liquid Television or Spike and Mike’s Animation Festival. It’s no weirder than many things. This is what I love about it.

Gerasimov told Forbes (of all places) that he believes the series is popular because it “doesn’t feel generic or corporate.” Most of the culture we are served is familiar — “war between good and evil,” say. So it is a delightful kind of disorientation, panic even, to encounter something that is playfully hostile to the familiar.

At the atomic level of the internet, that’s what everything is trying to do — be playfully hostile to the familiar. Most of it turns out to be too playful, or too hostile, or too familiar. Or just insane and unintelligible. What emerges from the nuclear reactions is a new element. What you might call art.

One defining feature of Skibidi Toilet is the chant-song used by the toilets as a kind of language, with about the complexity of birdsong. The song in question is a mash-up of a Nelly Furtado lyric mixed with a chorus from the Turkish singer Biser King that goes “brr skibidi dop dop dop dop yes yes yes yes.” (Memes aren’t so predictable though. The “skibidi dop dop” song actually became popular through the videos of another Turkish gentleman, whose generous belly bounces hypnotically when he encounters a platter of food, a friend by a canal, or a tractor. But Gerasimov told one outlet that his inspiration was a take on the song from a bodybuilding influencer called Paryss Bryanne, who posted her version in January 2023 — a few weeks before Skibidi Toilet’s first episode dropped.)

The series has covered a lot of ground in its 70-plus episodes, but the toilet and the song were there from the first video, which you can tell Gerasimov sort of tossed off… the result, he says, of recurring, toilet-themed nightmares.

Within a few episodes, a plot resolves from the glitchy animation: The toilets are now invaders, transforming humans into more toilets. And soon enough you have “Cameramen” and “Titan Speakerman” and the rest.

Skibidi Toilet looks like a video game because it’s made from video games. Game companies encourage fans to use their assets — their characters and objects and landscapes — for all sorts of things. It’s a genre called machinima (machine + cinema). This isn’t new. Twenty(!) years ago, an upstart company in Austin called Rooster Teeth created a hit online comedy series, Red v. Blue, about inept soldiers. It was based on characters from the game Halo.

Gerasimov uses a 3-D animation tool called Source Filmmaker; some of his characters are derived from games like Half Life 2.

This may all seem needlessly forensic. And you are right. The details are as irrelevant and essential as evolution itself. Because they reaffirm the one truth of the internet: There is no finished, there is no complete. No one can be sure their version is the final version. Everything good enough or bad enough or strange enough is the potential raw material for some new thing. Everything online is just waiting, pluripotent.

***

None of this may convince you of the value of Skibidi Toilet. A year and a half in, there is nothing to suggest that it is our War and Peace. Therefore, it’s in a great place. It’s both stupid and smart. Some fans love the bangs and booms and the utter silliness; I like that well enough. But I can also tell you that I’ve thought a lot about how the series is saying some interesting things about the endless escalation of war, and about how we glorify self-surveillance, and about how technology alienates us from our own bodies. You can stare at me for a beat and then call me a goddamn idiot. We are both right! This is the liberating power of art.

The success of Skibidi Toilet has spawned a massive and growing ecosystem of fan-created spinoffs and recaps and similar. Because Gerasimov isn’t a litigious corporation guarding its IP like a dragon sitting its gyat on a horde of gold, the exchange of ideas is fertile. Some good, some bad, but certainly closer to the creative world before copyright, the open-source flourishing of the Renaissance at the speed of the modern internet. The same kind of human that told and retold the Iliad and stories of Coyote around a communal fire, many unnamed generations later, riffs on the eternal conflict between toilets and A/V equipment.

Tune in, child, focus.