In 2019, Active Shooter Drills Are the New Fire Drills in Schools

With gun violence on the rise for the first time since the 1990s, active shooter drills are becoming a “normal” part of the school day. Here’s what kids are being taught and why.

Announced over the public address system in a suburban Philadelphia middle school:

The school is now on lockdown. This is just a drill.

Run!

Immediately search for a way out, any way out. Run through the classroom door. Climb out the window. Sprint through the football field. Run in a zig-zag or swirly line — a shooter is more likely to hit you when you run in a straight line. Hide in a neighbor’s garage until you know you’re safe.

Hide!

Do anything you can to make sure you aren’t seen. Pull a screen over the door so no one can peer into the room. Get away from the windows. Go toward the wall adjacent to the hallway. Huddle under a desk. Squeeze into a cubby. Take refuge in the closet. Don’t make a sound.

Fight!

Push the desks against the door as quickly as you can. There’s no need to stay quiet — the desks are already making too much noise. By now, you’ve been taught that every item in your classroom can be used as a weapon: staples, pencil sharpeners, pencil bags, books, computers, chairs. Get something in your hand, hoist it above your head, and be ready to throw it the moment the shooter comes through the door.

While school-shooting drills vary from school to school, this is how Maeghan Mclain, 12, described the way she has been taught to react when the principal announces an active shooter drill over the loudspeaker of her school.

For Maeghan, this is just a normal practice. For her mother, it’s something scarier.

“It’s not as terrifying for them as it is for us,” Maeghan’s mother, Claire Mclain, 43, told WhoWhatWhy. She grew up in the era between the Cold War’s “duck and cover” drills and today’s active shooter drills, making her unaccustomed to the normalization of violent threats in schools.

“It’s become the norm. As long as my kids have been in school, they’ve had school-shooting drills. It’s become just as common as a fire drill.”

In the age of Parkland, Santa Fe, and Sandy Hook, schools across the country are implementing active shooter drills into their emergency preparedness plans. Firearm homicide rates had been on a steady decline since the peak of US gun deaths in 1993, dropping by 49 percent by 2010 according to the US Department of Justice.

But a 2018 study by the CDC reports that firearm homicide has taken an opposite trajectory recently, with rates creeping back up toward levels comparable to a decade ago. Many schools follow the run, hide, fight model, which the US Department of Homeland Security recommends in response to an active shooter incident.

Claire Mclain is the mother of three children: Maeghan, Gavin, and Caitlin — ages 12, 11, and 9 respectively. The family has moved around a lot for Claire’s and her husband’s jobs, so their kids have gone to four different schools across Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania, where the family currently lives.

“Our schools have all been based on the run, hide, fight model,” Mclain said. “Each section of the building is assigned a different reaction for each drill, so one part would do run, one would do hide, and one would do fight.”

“I think hide is the most terrifying, though,” Mclain continued. “I was in the classroom as a guest one day during a drill. I hid behind a garbage can in a second-grade classroom. No one made a sound, no one moved. They all knew their spot. It was one of the most impressive and terrifying things I’ve ever seen an 8-year-old be able to do.”

Because school-shooting drills are meant to prepare students for any instance in which a firearm might be found at school, the firearm homicide rate might not matter as much as the overall presence of guns on school grounds. A shooting database put together by the Naval Postgraduate Group, which accounts for each time a gun is brandished or fired on a school property or a bullet hits a school property, found that 2018 was the worst year on record for firearms on school grounds and gun-related deaths in schools.

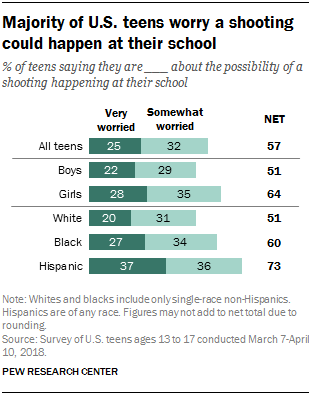

Recently, gun coverage in the news has kept the danger of school shootings on many people’s minds. As of 2018, 57 percent of teenagers and 63 percent of parents in the US worry about school shootings in their schools, according to a Pew Research Foundation study. In the age of social media, these tragedies are all the more accessible, and more real, to younger students.

“Stuff about school shootings interest[s] me,” Maeghan Mclain said. “Sometimes when I’m bored, I look up videos of Sandy Hook and other shootings to see what happened. It’s just so unbelievable to me that someone could actually want to do that, that it’s their goal in life to kill people, and to make everyone’s lives awful.”

“I always treat these drills like they’re real because it could really happen to us,” she added.

School shooting drills, when executed improperly, can unsettle a positive learning environment and cause psychological harm to students and staff, according to the National Association of School Psychologists. However, the NASP argues that appropriately planned drills — as a regular part of a school’s emergency preparedness program — can make students and staff feel more secure without inducing an undue sense of anxiety or safety.

Michael Mahon, the superintendent of the Abington Heights School District in northeastern Pennsylvania, explains that these plans need to take the community’s emotional state and expectation into account as well.

“We have always had, and always will have, a focus on safety,” Mahon said. “But recent events have put safety on the forefront of everyone’s minds. Some parents are afraid to send their kids to school, and they rely on the school district to do everything possible to keep their kids safe. That’s why school shooting drills have taken prominence in the school district so our students, faculty, and staff know how to respond in the case of an emergency.”

“Every school is different, so every school needs to create a plan that works best for them.” He continued, “We listen to our community, we review what’s best practice and what is required of us under school law, and we try to come to an appropriate balance that meets the needs and values of everyone involved.”

Andrew Snyder, the Abington Heights High School principal, has seen these plans evolve throughout his 19 years of working in education. He noted that the students are increasingly aware that this is more than just a drill.

“When I first got into education, if we did some sort of lockdown drill, maybe three-fourths of the students took it seriously,” Snyder said. “That number might even be lower. What I’m seeing from the students now is that they are more focused, serious, and understanding of why we do these drills. They see the news, and they know that this very well could happen at any school.”

Some parents in the district, however, worry that these drills might make students too accustomed to the idea of school shootings, thereby normalizing this type of violent incident, according to superintendent Mahon. Snyder disagrees.

“I don’t think it desensitized them,” Snyder said. “It allows them to prepare for it so when that they get into a situation where their adrenaline is spiking, their heart rate is reaching a point where they may be unable to react, they already have a plan worked out.”

Schools practice drills to ensure that students are prepared in the event of an emergency, but administrators are careful to make sure they know only what they need to know to keep themselves safe.

“Law enforcement is the only outside group that knows every detail of our plans,” Snyder said. “Even with students, we don’t go into 100% specifics. We trust that teachers can keep the kids safe because, unfortunately, with school shootings, the shooters are often students there. If you tell them every detail of every plan, any plan can be beaten. We only tell the students what they need to know to stay safe.”

Research by Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit advocacy group co-founded by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, found that 80 percent of active shooters in schools are connected to the school, and the Naval Postgraduate School study found that the majority of these shooters are current students at that school. Abington Heights High School has seen this trend in threats within their own district.

“Have the words been spoken about school shootings in our school? Yes, and they have been public,” Snyder said. “Has there been any proof of a worked-out plan? We’ve yet to find evidence of that. We’ve had kids say that someone should just shoot up this place, and that has put a scare through the community. We thankfully haven’t had a legitimate, verified threat. When we’ve had scares in the past, it’s mostly just kids speaking irresponsibly.”

As the presence of firearms in schools rises and active shooter drills are becoming more common in schools across the country, this trend has prompted nationwide debates among psychologists, school administrators, parents, and students about whether they do more harm than good.

“When you become a parent, the way you see these events in the news instantly changes,” Mclain said. “Your mindset goes from ‘This could never happen to me’ to ‘Oh my gosh, what if this happens to my children?’ I’m not sure if they make me feel more safe or more fearful. Either way, drills keep that fear in the forefront of my mind, and I’m sure, the students’ minds too.”

Related front page panorama photo credit: Adapted by WhoWhatWhy from US Marines.