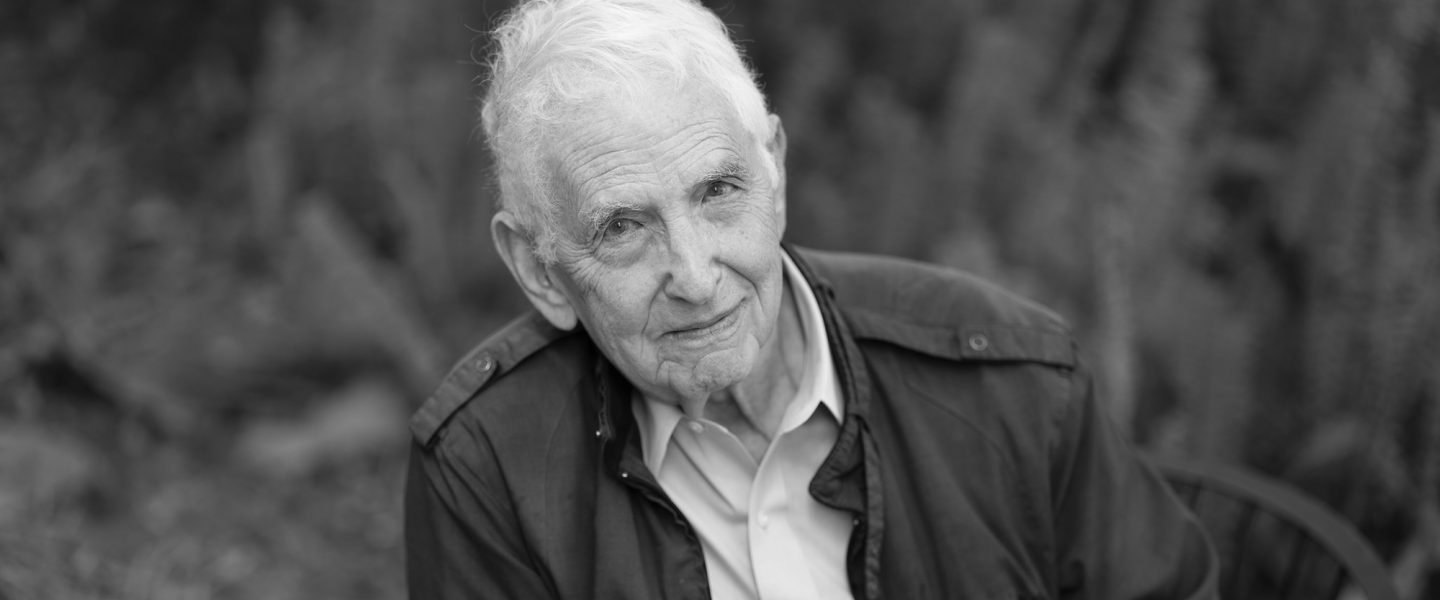

Daniel Ellsberg: Remembering a Gentle Giant

A few things you might not know about the Pentagon Papers whistleblower.

|

Listen To This Story

|

The last time I saw Dan Ellsberg was at a journalism conference a few months back. I was there and he was on the screen remotely.

It was just him, and his fellow whistleblower Reality Winner, speaking with the attendees about what it’s like to take great risks in service of the public good.

Although the audience was journalists, who have been important allies of Ellsberg throughout his life, he was, characteristically, blunt. He criticized our tendency to use sources and discard them. Because of the authenticity and heartfelt nature of the critique, it seemed like everyone took what he said as true. Personally, I couldn’t help but roar my approval.

A few days later, having sent Dan a note to say that I understood he had more important things to do than see me, I mentioned being in the audience for his remarks.

He wrote back:

Dear Russ: Thank you so much for that welcome feedback! I didn’t know if I might be offending some there, but it’s not the time for me to worry about tact.

I’m about to join a virtual reunion of the Rocky Flats Truth Force, which will take up most of the afternoon. (I have to take time out for naps — something to do with my condition). So I don’t think we can get together today; but I’m glad to hear from you!

That was April 29. He knew he only had a few months left at most because of his fast-spreading pancreatic cancer. By June 16 he was dead.

****

Dan Ellsberg first came on my radar when I was a child, long before he was well known as the nation’s most famous whistleblower from the unprecedented Pentagon Papers case, in which he’d smuggled out of the Pentagon a massive report showing that the government was lying to the public about how the costly and bloody Vietnam War was going.

Growing up in Los Angeles, I attended the same experimental elementary school as his children. His daughter, Mary, was my classmate.

One day, for “show and tell,” Mary brought a beautiful doll from Vietnam. As I recall, she said something like, “My dad is a secret agent in Vietnam.”

It was a long journey, from gung-ho Marine and intelligence analyst to peace campaigner.

Dan’s conversion deeply affected his children. His eldest, Robert, became the publisher of books relating to the social gospel, including the diaries of Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker newspaper and a seminal general-interest book, JFK and the Unspeakable, by the theologian James Douglass.

Robert and I reconnected over our shared fascination with the copious evidence that the truth about John F. Kennedy’s assassination had not been shared with the public. The JFK book that Robert published and my own deep dive into the US power structure — Family of Secrets: The Bush Dynasty, the Powerful Forces That Put It in the White House, and What Their Influence Means for America — both probed the value system behind the Establishment that his father had once served.

Dan Ellsberg, of course, as the Pentagon Papers whistleblower, knew all about cover-ups.

Still, Dan didn’t much like my interpretation of something else I found when doing my research on Watergate (as described in Family of Secrets): It was my conclusion that Nixon, for all his catastrophic faults, had not been the real culprit in that sordid episode, but had been set up — with the military (and CIA) as the chief villains.

Dan had been on Nixon’s enemies list, his psychiatrist’s office had been burgled by operatives tied to the Nixon administration, and he understandably had trouble excusing Nixon for anything. Nevertheless, despite his initial dismissal of my argument, he reread what I wrote and indicated that he was open to rethinking his position on the matter.

This was typical of him. He had a healthy ego but was also much more humble than he needed to be. And he struck me as a lifelong learner. He’d ask questions and solicit opinions when he wasn’t entirely sure what to think. How many big names do you know like that?

Dan spoke softly in general, had a sort of reserve and a formal air about him — sometimes one felt the emotional hesitancy — some of which undoubtedly came from family tragedy. As his granddaughter noted in an essay: when Ellbserg was 15 and riding in the family car, his father fell asleep at the wheel; Dan’s mother and little sister died; Dan recovered after falling into a coma.

Despite the sense of trauma one felt lingering, he was a mensch and he always signed his emails, “Love, Dan.”

He spent his post-Pentagon-Papers life engaged in a never flagging pursuit of peace and social justice, with notable work on reducing the risk of nuclear war, among many other issues. The one-time Establishment cog became a fearless dissident, a man who worked tirelessly, against great odds, to make a difference.

Daniel Ellsberg will be greatly missed. There aren’t many in his league. But we should all seek to at least emulate his high standards.

Daniel Ellsberg was a member of the WhoWhatWhy Advisory Council.